Knox Cave: Mysteries geological and historical await intrepid explorers

Most New York State caves are closed to visitors from Oct. 1 to May 1. For information about Knox Cave and other area caves, visit www.northeatserncaveconservancy.org.

Filled with darkness and featuring passages that twist and meander, caves by their very nature evoke legends and lore. Under one of the fields outside of the village of Knox, an eponymous cave has incited geologic interest and lore, and drawn explorers and scientists — and, from time to time, tourists — since the 19th Century.

Old histories of the Helderbergs make mention of its steep-sided entrance sinkhole though they do not record any exploration. Formed from the Devonian-age Manlius and Coeymans limestones, the cave consists of a series of parallel passageways on multiple levels formed along great vertical fractures in the rock called joints.

Knox is not among the longest or more challenging of the caves of the Northeast — it has around 4,000 feet of passage and only two sections require technical climbing (involving ropework). However, its notorious Gunbarrel passage (of which more later) and an arduous climb and crawlway that lead to the remote and once-beautiful Alabaster Room as well as the cave’s many legends have attracted sport cavers and scientists for many years.

Newspaper accounts dating to the 1920s report sometimes fanciful— or wishful — excursions into the cave, believed then to be miles in length. There were also apparently limited commercial excursions offered by members of the Truax family that owned the cave prior to the 1930s.

One can imagine hardy explorers venturing into the cave in the long-ago style made famous by Lester Howe in his own cave in the 1800s, scrambling over fallen boulders and through chilly pools, clad in canvas cloaks and bearing kerosene lanterns.

At some point in the 1930s, the Truax property was purchased by a retired couple from Long Island, Delevan C. Robinson — known as “D.C.” — and his wife, Ada. D.C. held a Ph.D. from Carnegie Tech and his wife had a master’s degree and had taught English on the secondary level.

He built an elaborate series of stairs that descended to the floor of the cave (over 110 feet underground) and he installed electric lighting in a section that was to be a tourist route. Wishing to keep his cave in a natural state, D.C. made walkways out of flat slabs of Manlius limestone from which lower levels of the cave were formed. As an additional draw, he built a large roller-skating rink that at times also functioned as a dance hall.

The problem that D.C. and others who attempted to commercialize Knox Cave encountered was the fact that, although the section of the cave easily accessible by the staircase featured several large, impressive chambers, tours lasted only about 45 minutes. This was far shorter than tours at nearby Howe Caverns, and those areas lacked an atmospheric gurgling stream such as Howe’s “River Styx” or any flowing water for that matter — a most curious fact for a New York State cave.

Some of the most interesting sections lay beyond the famous (infamous?) Gunbarrel. This is a 47-foot-long tubular passage, and its average diameter is only about 14 inches (that is not a typo!) through which paying customers could hardly be expected to squeeze.

In any event, in the early 1950s, D.C. also set out on an ambitious program of exploration in an attempt to find new and more accessible passages and to prove that Knox — known then to be only about 3,000 feet in length — was the longest cave in New York State.

Negley’s exploration

To that end, he enlisted a shadowy figure known as “Buck” Negley who was apparently a postal worker, spending his free time exploring Knox. Very short in stature and wiry, Negley could slither through cracks and crevices that many people would regard as impossible and he evidently did much of his exploring alone. (Serious violation of caving rules!)

Prior to his explorations, the cave was known to continue beyond the intimidating Gunbarrel to a roomy chamber that terminated in a pile of loose rocky debris. Pushing aside boulders and slabs (and probably placing his life in jeopardy), Negley was able to squeeze through and discovered a maze of lofty canyons and domes and a yawning pit.

He also navigated his way through a tight, tortuous passage known as the Crystal Crawlway for its pockets of calcite crystals and was able to climb down into what became known as the Alabaster Room. Once admired for its displays of milky, translucent stalactites and flowstone, the chamber today is a sad sight.

Incredible as it might seem, some of the visitors to this remote, hard-to-reach grotto have damaged or carried away many of its delicate formations. Oddly — though the room appeared to be the northern termination of Knox Cave, Negley claimed to have found a passage continuing beyond it, for which explorers searched for years.

But in the 1990s determined cavers dug out a clay-clogged passage in a secluded spot below the Alabaster Room and broke into a low, thousand-foot-long canyon carrying a stream, far below Knox’s once-commercial passages, solving a mystery of Knox Cave’s hydrology and perhaps vindicating the legendary Negley.

But another of Negley’s claims has yet to be confirmed. He insisted that he had wormed his way through a tight crawl east of the old commercial sections and found a room he described as “larger than a football field.”

Many scoffed at his claim — but the fact remains that the thick Coeymans and Manlius limestone strata that cover many square miles of woods and fields around the village of Knox are filled with sinkholes and fractures carrying surface water to unknown destinations and in which large caverns could develop.

It is not inconceivable that the black vastness of Negley’s Lost Room may yet await discovery for some intrepid — or very thin — explorers.

Frustration Crawl and New Skull Cave

Another more tangible mystery involves a tight tunnel known as “Frustration Crawl,” which has tantalized explorers for decades. Cavers can enter it on hands and knees but it soon turns into a flat-out belly crawl, its walls worn smooth from the abrasion of thousands of passing bodies.

But, after a hundred feet or so, human intrusion is halted by two thick curtains of flowstone that have descended from either side. Looking through a narrow space between them, cavers can see that the tunnel continues but they cannot.

However, the crawl is headed straight for another large cave system less than 1,000 feet away known as “New Skull Cave,” a tortuous, wet, muddy cave system known to have over five miles of challenging passageway. Off limits to sport cavers for years, New Skull has not been fully explored and may well continue for additional miles.

Were “Frustration Crawl” to connect Knox Cave to New Skull there would be the potential for one of the largest cave systems in the Northeast.

And why the designation as “New Skull?” A few hundred yards away from both the Knox and New Skull entrances there once was a wide, vertical sinkhole around which legends abound. A local tale says that in the mid-1800s, a farmer climbed down some 60 feet into it and entered a dripping, gloomy chamber, the floor of which was littered with human skeletons and the bones of large animals.

Some versions of the tale say the animals were long-horned steers, others that they were the remains of a giant Ice-Age ground sloth. In any case, horrified by his discovery, the farmer dumped huge boulders into the sinkhole and then filled it to the surface with dirt.

The upper 10 feet or so of the sinkhole was still visible in the 1960s and geologic features in its walls called fluting indicated that in the distant past it had been the insurgence point for large volumes of water. Today, the sinkhole reputed to lead to what has come to known as “Old Skull Cave” is no longer visible, having been completely filled with soil making it level with the surrounding fields, but its memory adds to the legends of the area, a lure as tantalizing as “Frustration Crawl.”

Access to Lemuria?

Doubtless the weirdest legend associated with Knox Cave derives from the book “I Remember Lemuria” by Richard Shaver published in 1948. In it, Shaver claims that far beneath the earth and accessible through certain caves is a whole separate and highly advanced civilization called Lemuria.

Its super-intelligent inhabitants do not want intruders from the surface and so they have bred a race of huge ape-like creatures armed with clubs to guard the access points and bash in the heads of any surface people who happen to wander in.

Shaver asserted that one of the caves offering access to Lemuria was Knox. Surely no comment on this story is needed; however — when I have taken groups of schoolkids into the cave in one of my Heldeberg Workshop summer caving classes, I have found that recounting the legend to them is a very effective way to keep any of them from wandering off.

The last attempt to commercialize Knox Cave occurred in the late 1950s, and tourist brochures as well as other ephemera of the cave from that period survive. When I was a boy, my parents took me on what turned out to be among the last commercial tours of Knox.

Even as a youth, I knew that the descent from the surface on that stairway was going to be intimidating to many tourists, especially the elderly — a far cry from the elevator that carried visitors effortlessly into Howe Caverns.

Brief though the tour was, the guide’s recounting of the cave’s history and lore was captivating. He spoke of the high narrow fracture called “Skeleton Passage” in which six human skeletons had allegedly been found along with a number of ancient torches — their whereabouts even then unknown.

He also fascinated visitors with tales of a mysterious tablet in an off-limits section of the cave which had inscribed upon it the hieroglyphic writings of the Nephites, who Mormons believe inhabited North America in the years before the Christian Era. (These subsequently proved to be natural solution channels carved into the Manlius limestone by dribbling acidic water.)

And the guide hinted at new discoveries which might stretch the cave’s length to 13 miles — an elusive goal, to say the least.

By the time the cave closed for commercial tours for the final time, D.C. Robinson had passed away, but the cave remained open for sport cavers and scientists. His wife, Ada, was known to all as a delightful woman who enthusiastically welcomed visitors, telling them perhaps wistfully that the cave had been “entered but not explored” for 13 miles.

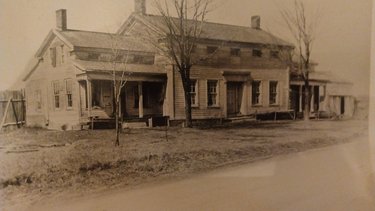

Readers acquainted with “Aunt Arie” from the Foxfire books would have recognized her double in Mrs. Robinson with her print dress and apron, hair in a bun, and effervescent personality. Upon her death in 1964, the cave went through a period of confused ownership during which people came and went freely onto the property and into the cave.

Fires determined to have been arson destroyed first the abandoned skating rink and then the Robinson house.

Then, in 1976, a group of college students attempted to enter the cave in winter, crawling through an opening in a mass of ice that blocked the entrance. A huge chunk broke off, killing one student and seriously injuring another.

Another period of confusion followed but eventually Knox Cave was acquired by the Northeastern Cave Conservancy that now controls access. The nearby Knox Museum features a Knox Cave room, filled with photographs, memorabilia, and newspaper articles from the cave’s glory days, as well as plaster impressions of the “Nephite hieroglyphs.”

And so, from May 1 to Oc. 1, both sport cavers and scientists from all over the world hike the surrounding fields past the disintegrating ruins of the Knox Skating Rink and descend the gaping sinkhole to explore and study the cave’s geologic mysteries.

The vast entrance rooms still astound, the claustrophobic Gunbarrel still calls explorers to the chambers beyond, and reaching the long-unknown river passage still challenges cavers’ strength and endurance. And perhaps from some dark recess, the ghost of the mysterious Buck Negley urges the intrepid to push beyond one last tight squeeze that opens into an echoing chamber the size of a football field.