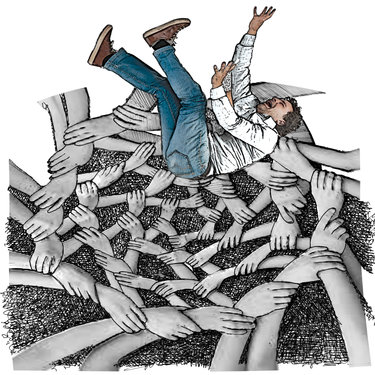

For a safety net to work, everyone has to hold up their end

A 25-year-old man, Zachary Barrantes, tried to kill himself on New Year’s Eve by jumping off of a cliff at Thacher Park.

The rescue at the state park was heroic after the Albany County Sheriff’s search-and-rescue team found Barrantes three days later at the base of the cliff, still alive despite having spent three frigid nights there. It took four-and-a-half hours for the trained team to perform the difficult task of lifting him, bit by bit, up the sheer rock wall — 300 feet — to where a helicopter waited to airlift him to Albany Medical Center.

We commend the rescue team for its work. Saving a life in that way is not an easy task. It takes the right training, the right equipment, and, perhaps most importantly, courage — team members risk their own lives to save a stranger they don’t even know.

But there is more to the story, more to the rescue than what occured on Jan. 3 when Barrantes was saved. Our reporter Sean Mulkerrin told the rest of the story last week on our front page and we believe it should serve as a guide to larger problems that need to be solved.

Before Barrantes was securely roped and pulled to safety up the cliff face, other safety nets had failed him.

His family, particularly his mother, Daniela Filmer, is the reason he was found at Thacher Park. She had called the Albany Police, trying to locate her missing son. She did not get the help she needed.

Barrantes lived at the Equinox Recovery Residence in Albany, which, Filmer said, was supposed to contact her if her son left. He had a pass to go home for New Year’s Eve but Equinox didn’t call, Filmer said, until the pass had expired, more than a day after he had jumped off the cliff.

Filmer logged into her son’s bank account and saw there had been a $25 charge from Uber, the rideshare company. By looking at his Gmail account, Barrantes’s family found the receipt that showed Barrantes had been picked up at 326 New Scotland Ave., the Equinox address, at 10:24 p.m., on New Year’s Eve, and dropped off at Thacher Park at 10:56 p.m. that night.

With that information, the rescue team could start searching for him. The sheriff and park police were upset, Filmer told The Enterprise, that they hadn’t received a missing-persons report and precious time had been wasted.

Barrantes’s survival was not luck; it was the persistence of his mother that led to his rescue. An Albany Police detective showed up at Albany Medical Center and “apologized profusely over the way that was handled,” Filmer told The Enterprise; he said that the lack of response would be “addressed” with the officers involved.

It needs to be. As citizens, we depend on police to file reports and to try to find missing people in a timely fashion. On a cold night, a life can hang in the balance.

But the systems that failed Barrantes are deeper and wider than that. He suffers from mental illness. As Filmer told Mulkerrin — and cited the records to back up her story — her son’s problems began with grief over the death of his father when Barrantes was 16. This was compounded by chronic Lyme disease at age 19 and depression, and finally a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Mental illness is just that — an illness. And it is not uncommon. Nearly one in five United States adults live with a mental illness, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Someone with mental illness deserves our compassion and is entitled to treatment.

What Barrantes suffers from would be classified as a serious mental illness, something he has in common with 4.5 percent of adults in the United States, young adults most frequent among them.

The consequences can be dire for a society if mental illnesses are not properly treated. The problems Barrantes has faced in his short life illustrate this point. At the same time, his struggles are emblematic of those documented in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

In 2016, Barrantes had developed hand tremors and received a medical marijuana prescription that helped him at first. The Northern Rivers clinicians’ impression of Barrantes after that was, due to complications from Lyme disease and his hand tremors, it had been “evident that Zach’s sense of managing his body” had led to a “hopelessness and depressed mood.” In addition, it appeared that his “depression and sense of self also shifted and was present following the loss of his father, at the age 16.”

But the clinicians concluded Barrantes didn’t meet the criteria that would have admitted him to a program that may have helped him. Three weeks after that, he was picked up by police for walking into an active shooting range. The police report states that there was a “strong possibility” that his plan had been to walk in front of gunfire, which he denied.

Barrantes was then admitted as an involuntary patient to Albany Medical Center’s Psychiatry Department, his mother said, and his family wrote letters asking that he remain because he was “an imminent danger to himself.”

On July 27, 2017, hospital staff decided “we do not see imminent safety concerns that need to be addressed [by the] inpatient psychiatric unit,” and discharged Barrantes.

Upon discharge, he ran away. His family next heard of his whereabouts two days later, after he had stolen a car and crashed it into another car. He was sent to jail and then to an addiction treatment center where, his mother said, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

“And now as a result of that accident, a kid who was never ever in trouble with the law, a kid who has been eternally sad since his father died at the age of 41 while being treated for depression at Four Winds in Saratoga, a kid who has struggled with chronic illness — Lyme disease — is now a TWICE convicted FELON as a result of his unsafe discharge, and now if he violates his probation, no matter what, even if the judge doesn’t agree with the sentence it will be a mandatory SEVEN YEARS in a STATE PRISON,” Filmer wrote to our reporter, Mulkerrin.

The answer, not just for Barrantes and his family but for society as a whole, is effective treatment for mental illness, which is often paired with addiction. The two need to be treated together.

Of the 4.4 million young adults aged 18 to 25, like Barrantes, with a major depressive episode, about 2.2 million received treatment for depression in the past year, or about half, according to the Department of Health and Human Services report on Key Substance Abuse and Mental Health Indicators in the United States.

That’s not good enough. We can’t let half of depressed young adults fall through the safety nets our society has put in place. Barrantes has tried to kill himself three times, endangering others along the way.

We admire Filmer’s courage in sharing her son’s story and her tenacity in saving his life. Filmer said, after the Thacher Park rescue, that no single person or institution is at fault for what happened. Certainly, an individual has to set his own course in life, has to be responsible for his own action.

But when a person is sick, mentally ill, he needs the help of society at large to succeed. Government-funded treatment programs to supplement private insurance policies that will pay for treatment long enough to be effective are needed to stem the rising tide of addiction problems paired with mental illness.

Whose child is next to fall into addiction or suffer from mental illness? With such a net, we’ll all be safer. The person you save may be your own.