Editorial

Lesson from a Holocaust survivor: Forgive but don’t forget

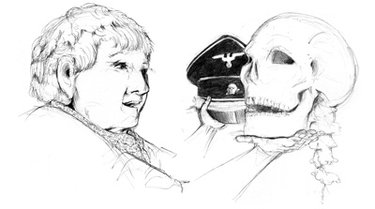

Illustration by Forest Byrd.

What does it mean to forgive?

For Eva Kor, it means to heal herself. It took a journey of a lifetime for her to come to that conclusion.

She and her twin sister, Miriam, were tortured in the name of science actually a perversion of science founded on the concept of a master race by Nazi Josef Mengele at the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Kor travels the world now, teaching three lessons: Never give up, end hatred and prejudice by seeing others as individuals and treating them with respect, and forgive. She spoke to a packed hall Monday night at The College of Saint Rose in Albany after the screening of the 2005 documentary, Forgiving Dr. Mengele.

The film tells her story how, at the age of 10, she and her identical twin sister, her two older sisters, her mother, and her father were sent to Auschwitz. She remembers being ripped from her mother’s grip as she and Miriam were “saved” for experimentation.

“I saw my mother’s arm, stretched out in despair as she was pulled away,” recalls Kor. She never saw anyone else in her family again.

“It’s a place where I lived between life and death,” Kor says of Auschwitz. She remembers being marched to the barracks and seeing the corpses of sweet children, their bodies naked and shriveled.

“Their eyes were wide open and looking at me. I was angry at them and asked, ‘Why did you permit yourself to die?’ I am not going to permit that for me and Miriam.”

Kor also says, “I thought that the whole world was a concentration camp. I concentrated on surviving one more day, one more experiment….”

She recalls at one point in her nine months at Auschwitz being injected with something that made her deathly ill. “I was placed in a barracks filled with the living dead,” she said. Mengele said she would be dead in two weeks.

“I refused to die,” she said. She recalls, in and out of consciousness, crawling on the floor to reach water. She knew if she died, her sister would be immediately killed, so comparative autopsies could be performed on their bodies.

“I spoiled the experiment and I survived,” said Kor.

The documentary intersperses gritty black and white pictures of Auschwitz during the war with colored vignettes of Kor’s life today, as a smiling real-estate agent, married to another Holocaust survivor in Terre Haut, Indiana, where they raised two children.

Period film of the liberation of Auschwitz shows Eva and Miriam Moza holding hands as they lead a procession of emaciated survivors through a barbed-wire gauntlet. The documentary ends with modern-day Kor walking that gauntlet, in a preserved Auschwitz, alone.

She told the crowd of about 500 on Monday, there was nothing for her at home after Auschwitz was liberated: “I found three crumpled pictures on a bedroom floor when I got home and that was all that was left of my family.”

She also said, “What I needed desperately [coming] from the camp was hugs and kisses from my parents or anyone, and I got none.”

In 1950, at 16, she and her sister got visas to Israel. They lived on a kibbutz with other orphans. It was, Kor said, the first time she slept without fear of persecution, marveling what it was like “just to be able to like yourself because you are a Jew.”

Her sister, a nurse, stayed in Israel. Kor married and moved to the United States. Kor remained protective of her sister: “I thought of Miriam more as her mother than her sister,” she said. Mengele had injected Miriam with something that stopped the growth of her kidneys and she became very ill. Kor donated a kidney to save her sister’s life. “I didn’t let her die in Auschwitz; I couldn’t let her die in Tel Aviv,” she said.

Doctors said it would help if they knew what Miriam had been injected with. Kor scoured books for answers and began wondering what had happened to other twins who had suffered through Mengele’s torture at Auschwitz. She founded an organization that put the surviving twins in touch with each other.

Miriam died on June 6, 1993, but Kor couldn’t lay her to rest. “After Miriam’s death, I was even more determined to find out what she was injected with,” she said. Mengele had died in 1979, having escaped to South America.

Kor tracked down Hans Munch, a Nazi doctor at Auschwitz and the only SS officer to be acquitted after the war, and arranged to meet with him. Kor approached the encounter with great trepidation. “Every cell in my body was revolting,” she told the crowd at Saint Rose.

Munch told Kor that Mengele spoke with no one about his experiments. Although Kor didn’t come away with the answers she had gone for, she left with something else the sense that this Nazi was human.

“To my great surprise, he treated me with kindness and respect,” Kor said.

Munch told Kor that he was very depressed after the war and found no joy in his freedom.

Kor asked him if he had seen the gassing at Auschwitz that had killed her parents.

“He said to me, this is the nightmare I live with every day of my life,” Kor told the crowd. “He was stationed at the gas chamber doors…He signed the death certificates.”

She asked him to come with her to Auschwitz in 1995 a year-and-a-half away for the 50-year celebration of its liberation.” Kor recalled telling Munch, “I want you to sign a document this happened.”

“He said, without hesitation, ‘I would love to.’”

She told the crowd on Monday, “I didn’t know where to look for a gift for a Nazi doctor would you know? I went to the Hallmark shop. I read many, many cards….I left after two-and-a-half hours, very discouraged.”

For 10 months, she asked herself how to thank Munch, rejecting hundreds of ideas, until she came up with this: “How about a letter of forgiveness from me to Dr. Munch?”

By that act, she said, “What I discovered for myself was a life-changing experience…No one could give me that power and no one could take it away.”

In writing and re-writing the letter, Kor worked through a lot of pain. To polish her prose, she met several times with a former English professor, who told her, “You really need to forgive Mengele.”

“I began to think about it I, a little guinea pig, the nobody, the nothing, had the power to forgive the god of Auschwitz”

At the ceremony in Auschwitz in 1995, Kor read her letter, and says she felt a great weight lift from her shoulders.

“The day I forgave the Nazis, I forgave my parents whom I had hated all my life,” she said on Monday. “I finally understood that my parents did the best they could. I call forgiveness a modern miracle medication….”

Kor also said that she felt she had victimized her own children. She told of a trip she took with her daughter to lecture in Germany where, feeling pressure because she had left her speech at home, she yelled at her daughter. “I thought, since you forgave, you stopped yelling,” her daughter, Rina, said to her.

“People who are angry will take it out on whoever is closest,” confided Kor, “and it’s often our children.” She said it is important to break the chain.

Kor recently traveled to another concentration camp, Buchenwald, where her husband had been imprisoned. She laid flowers there with the children and grandchildren of Nazis. Kor tells those children that they cannot help their heritage and should not be burdened with its guilt.

“I actually wanted to dance the Hora,” she said, although her son said no. “We are rejoicing that we survived in spite of everything.”

Last week, on Yom Kippur, Kor’s husband, Michael, after 65 years, forgave the Nazis as well. With prodding from his wife, he wrote a letter, which she read to the listeners at Saint Rose on Monday night. He recalled how the Nazis had sadistic smiles on their faces as they beat their prisoners. He also recalled the silent jubilation he felt each morning in just waking up, still being alive. His hate for the Germans has diminished, he wrote, to the point where he can root for a basketball player who theoretically could be the grandson of a concentration camp guard.

“My husband, after 65 years, finally relinquished the pain and mentality of victimhood,” Kor told the crowd to loud applause. “If my husband can do it, who was an ardent victim, anyone can do it.”

Kor believes what finally got her husband to write the letter is, for the last six months, she’s been forwarding him letters people have sent her, reflecting on the idea of forgiveness. She is now forwarding the letters to Israel, to other Mengele twins.

She said to resounding applause on Monday, “Help victims heal themselves one victim at a time. To me, that would be the greatest way to get even with Hitler and the Nazis.”

But the producers of the documentary, Bob Hercules and Cheryl Pugh, did not leave Kor’s story with her statement of forgiveness. They interviewed other surviving twins who felt angry or betrayed by Kor’s public act of forgiveness.

Kor responded, “Most of my fellow survivors are so hurting they do not have the ability to understand what I am talking about. So many of them will die without ever being free of the pain.”

She said of her own decision, “Just being free of the Nazis did not remove the pain they inflicted on me…I had no idea I had the power to forgive a Nazi.”

Kor told the crowd at Saint Rose on Monday, “Some survivors are afraid, if they give up their pain, there is nothing left…You can always go and take your pain back. There is no Pain Police to stop you.”

The documentary also includes scenes where Kor is questioned harshly by those she is lecturing. When asked if there shouldn’t be criteria, such as remorse, for the person being forgiven, Kor responds, “Forgiveness has nothing to do with the perpetrator or with any religion….It only has to do with the victim empowering him- or herself.”

The producers also interview Michael Berenbaum, identified as a “Holocaust scholar,” who says, to grant forgiveness, “I demand and I require gestures, acts, deeds of enormous significance. I’m against cheap grace.”

Kor stresses that, by forgiving, she is not forgetting. She built a Holocaust museum in a strip mall in Terre Haut, where she spoke with thousands of visitors. It was burned out on Nov. 19, 2003, and the arsonist has never been caught.

Among the ashen remains were shattered jars of pennies. “These pennies were collected by students…a penny for each victim that died in the Holocaust,” says Kor, as the film shows firemen, kneeling in the muck after the blaze has been quelled, carefully, picking up penny after penny for her.

Kor rebuilt the museum.

“Everything we do in our lives is like a ripple on a lake…it has far-reaching effects,” says Kor.

The documentary also points out that Kor has reconciled with Germany but has trouble reconciling with the Palestinians. Kor says there is “no problem reconciling after the guns are silent,” and asks, “How do we get to that point?”

The film includes an interview with Ami Adwan, a Palestinian professor of education who says he was beaten many times while jailed by Israelis. “I don’t know if I’m reaching the point of forgiveness,” he says, conceding, “I’m reaching the point of understanding.”

Adwan and a group of other Palestinians tell Kor of their suffering at the hands of Israelis. Kor tells them, “I don’t want to hear eight, nine stories of suffering. I know everybody’s story.” At the same gathering in Palestinian territory, Linda Livni, a Jewish peace activist, tells the group that, in establishing Israel, there was much fighting at the beginning. “We did not see any other people but enemies…Arabs out to kill us.” Fifty years later, she said, co-existing on “this little piece of land,” it’s a trauma for Israelis to say, “What have we done?”

“The idea of forgiveness cannot work when people are fighting for their lives,” Kor says in the film.

She said at Saint Rose on Monday that the original idea of the meeting was to discuss a textbook that described recent history from both the Palestinian and Israeli points of view, with the middle blank for students to draw their own conclusions. Kor said she felt trapped by what took place and sobbed uncontrollably when it was over. “I became a victim, against my knowledge,” she said. Kor watched the film five times to figure out why she was acting so strangely.

“If you cannot do what you want to do, within the law, you are a victim, and I became a victim,” she said.

Two questions from the largely appreciative crowd in Albany on Monday night got to the heart of Kor’s philosophy.

One young man stood to ask, “How do you forgive someone like Dr. Mengele?”

“Can I change what happened?” asked Kor.

“No,” the young man replied.

“Can you change what happened?”

Again, the answer came: “No.”

“Can I change Josef Mengele?”

“Probably not.”

“Forgiveness,” concluded Kor, “is not because Mengele deserves it but because I deserve it.”

Finally, a white-haired teacher of world religion, who said how much he admired Kor, asked for her ideas on God and heaven and hell in relation to forgiveness.

“You’re not going to like me any more,” replied Kor. “I was a religious little girl.” Her first night in the concentration camp, she said, she would not eat the bread because it was not kosher.

Then, she said, “I saw the dead children on the floor and realized it could happen to me. I had to discard everything I was before, and eat the bread. How could God be in Auschwitz?”

Kor concluded, “I do not know if there is a god or there isn’t….But that has nothing to do with forgiveness…I was not a Christian or a Catholic; it did not relate to me. If someone said, every human being has a right to live free, I might have forgiven a lot sooner.”

“I still love you,” said the questioner.

Melissa Hale-Spencer, editor