Reefer Madness — ignoring the benefits of medical marijuana

Medical marijuana is in a Catch-22.

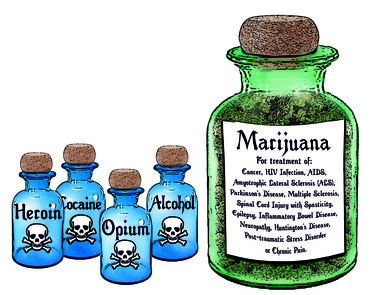

The Federal Controlled Substance Act classifies cannabis in the strictest category, Schedule I, along with substances like LSD and heroin, meaning it has “no currently accepted medical use in the United States, a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision, and a high potential for abuse.”

Because of this, it is difficult for scientists to get funds and cannabis itself to do the extensive testing required to have a drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Marijuana is now legal for medical use in 29 states and the District of Columbia yet, at the same time, use of marijuana is considered a crime by the federal government.

Why does this inexplicable disparity exist?

Because hippies smoked pot in the 1960s.

The conservative Republican administration of Richard Nixon commissioned a report in 1972 that included a description of marijuana’s uses as a medicine through history — in China, Egypt, and in America from the mid-19th Century to the 1970s.

“In large measure,” the report said, “the marihuana issue is a child of the sixties, the visual and somewhat pungent symbol of dramatic changes which have permanently affected our nation in the last decade … We would de-emphasize marihuana as a problem.”

Nearly a half-century later, it is time to let go of the prejudice some may hold against a plant that came to symbolize dramatic change.

Fourteen years ago, when we advocated in this space for New York State to legalize medical marijuana, we quoted the FDA’s Robert Myer addressing a congressional subcommittee on the “potential merits of cannabinoids for medical use.” He said, “Despite its status as an unapproved new drug, there has been considerable interest in its use for the treatment of spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis, and chemotherapy-induced nausea.”

Two years ago, New York’s Compassionate Care Act went into effect, allowing New Yorkers to get the medicine they need for a limited number of serious diseases.

Now we have a chance to make further progress. Our interest in the issue was piqued this week with a letter to the editor from Alisha Betti, a state-certified medical-cannabis-prescribing pharmacist. Her brother lobbies for legal, medical marijuana.

Betti writes in support of a Senate bill, sponsored by Diane Savino, a Democrat representing parts of Staten Island and Brooklyn, who has worked as a caseworker and was the State Senate’s lead sponsor of the Compassionate Care Act. Our Guilderland reporter talked to Savino’s counsel, Bryan Clenahan of Guilderland, and learned that Savino is working on three bills relating to increasing patient access to medical marijuana. Clenahan said that three interrelated things need to be improved: the cost of the drug has to be reduced, more providers are needed statewide, and more patients should be served.

There are currently about 1,500 providers in New York, he said, serving about 52,000 patients although only a third to half of those patients are active. There’s only one lab doing the testing, which was causing a bottleneck. We’re pleased procedures have been changed there, increasing testing capacity by 25 percent, according a spokeswoman for the State’s Department of Health, Jill Montag, and eliminating the backlog. We were also pleased she said the department is committed to responsibly increasing the medical-marijuana program.

Albany County has just two dispensaries — in Stuyvesant Plaza and on Fuller Road near Central Avenue, near to each other and hard to get to for patients on the outer edges of the county.

Across the nation — and right here in Albany County — an opioid epidemic is taking lives and causing spikes in crime while reducing productivity.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, some studies have suggested that legalization of medical marijuana could be associated with decreased prescription opioid use and overdose deaths. A study funded by the institute showed that legally protected medical marijuana dispensaries, not just medical marijuana laws, were associated with a decrease in opioid prescribing, in self-reports of opioid misuse, and in treatment admissions for opioid addiction.

Beyond that, the institute reports that treatment with medical marijuana could reduce the dose of opioids that patients need to manage pain.

We commend New York on the progress that has been made — thousands of patients can now get the medicine they need without resorting to pot they formerly had to buy on the street, unsure if it were safe or not. But we urge our legislators to do more — particularly in light of the opioid crisis — to make the current system more efficient, with more than one processing plant — and with more dispensaries so that those in need can more easily access their medication.

Most importantly, the big picture, on the federal level, needs adjusting. Although the majority of states are enlightened enough to allow medical marijuana, the Schedule 1 classification means the needed funds and medical marijuana for trials are hard to come by. Without the trials, the FDA can’t approve the drug even though its spokesman testified before Congress 14 years ago on its potential worth.

It’s time for scientific evidence to trump political ideology.