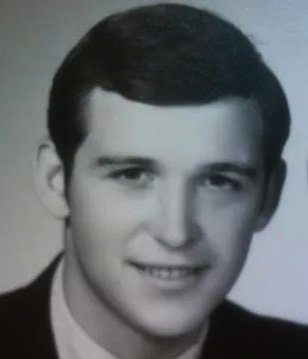

Frederick Roger Crounse

ALTAMONT — Frederick Roger Crounse died on Friday, Jan. 16, 2015, in the Brandle Road farmhouse where he was raised, the home he loved where generations of his family had lived — a rich history which he reveled in and preserved. He was 68.

“He was intelligent and compassionate,” said his daughter, Elizabeth Crounse, who had come from Arizona to Altamont to care for him as he faced cancer. She went on through tears, “The greatest gift he gave us was humor...He was just the funniest dad.”

She also said, “He loved classical music.” She recalled how, when she was young, he’d play marching music. “He’d march through the house and we’d follow him into the bathtub.”

Mr. Crounse had a serious side, too. He proudly served in the United States Air Force for 24 years, retiring in 1990 as a Chief Master Sergeant. He then worked for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization as a civilian, retiring and returning to Altamont in 2006.

“He just loved Altamont,” said Cindy Pollard, a long-time friend who, with her husband, owns the Home Front Café in the village. “He couldn’t wait to come back to family.”

Mr. Crounse’s Air Force jacket, complete with its many ribbons, was recently installed in a frame at the café, a community gathering place that features memorabilia from military service.

Mrs. Pollard met Mr. Crounse when she came to Altamont as a young bride. “Fred was 12. He’d deliver eggs from his family’s farm,” she recalled. “He was rather shy and very smart. I always liked him.”

She went on about the grown man, “He had a lot of friends. He was a fine man, a man who loved history, who loved his ancestors. He was a brilliant man with such a wonderful sense of community. And he loved to write; he wrote beautifully...He also had a great sense of patriotism. He loved American history and his family being a part of it.”

She concluded, “He was gentle of nature but very strong in character.”

Altamont boyhood

That character was formed in his youth as he was raised in a close-knit family. “Everybody always loved Fred,” said his sister, Pam Jones. “He was very funny — he was a clown — and very smart.”

Mr. Crounse was the middle of three siblings; his brother, Arthur Stuart MacCauley, known as Mac, was three years older and his sister was three years younger. Their father worked for the Veterans Administration. “He would get veterans benefits,” said Mrs. Jones.

Their mother was a homemaker who restored their 1829 farmhouse. “It was dilapidated and looked like a barn when we moved in,” recalled Mrs. Jones. She was 4 and Mr. Crounse was almost 8 in 1954 when the Crounses moved into their Brandle Road home, which had no running water and no indoor plumbing. Their mother made her own soap.

She also sold vegetables in a roadside stand and she cared for 1,000 chickens. “My mother would feed the chickens, wash the eggs in a machine, and candle and grade the eggs,” said Mrs. Jones. “My father and Fred had an egg route.”

Mrs. Jones and Mr. Crounse had a close bond, sharing a love of both reading and writing. As children, they put out their own newspaper, “The Altamont Blab,” on sheets of paper, filled with their stories and pictures, which they stapled together.

Some of their favorite authors included Thomas Hardy, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ambrose Bierce, John Steinbeck, Charles Dickens, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. “We liked the classics,” said Mrs. Jones. “He also loved science fiction.”

Mr. Crounse was a fan of old black-and-white movies and he and his sister shared a favorite, Cyrano de Bergerac, made in 1950.

“Fred and I took after my father. We’d have philosophical discussions around the table,” Mrs. Jones said.

The pair were “diametrically opposed politically,” said Mrs. Jones. “I was to the left, he to the right of center,” she said. “He was a strict constitutionalist.”

His sister listed a wide range of activities at which Mr. Crounse excelled in his youth. He played on a Kiwanis Little League team and was a good hitter. He also taught Sunday school at the Altamont Reformed Church. He remained spiritual throughout his life, she said.

As a sixth-grader at Altamont Elementary School, Mr. Crounse won the Honor Award from the Daughters of the American Revolution for his intelligence and good citizenship.

In recent years, Mr. Crounse wrote pieces for The Altamont Enterprise, capturing the sweetness of his youth. Upon the death of Judge Lawrence Walsh at the age of 102, Mr. Crounse remembered the judge not as the shaper of world events that he became but rather as the father of a boyhood playmate, the man who taught him to skip rocks.

“In those days,” wrote Mr. Crounse, “every self-respecting boy was expected to stock and manage a toolkit of essential skills. Rock-skipping was right up there with tying your shoes, playing baseball, riding a bicycle without training wheels, and effectively wielding a slingshot.”

He concludes, “For me, Ed Walsh will always be the man who taught rock-skipping to a 6-year-old boy on the waters of the Bozenkill beneath the Rickety Rackety Bridge on a summer day long ago.”

Manly pursuits

In 1964, for Government Day, Mr. Crounse was the student chosen to serve as town supervisor. He graduated that year as one of the top 10 students in his class at Guilderland High School. He was then given a full scholarship to study nuclear physics at Union College where he was in the Reserve Officer Training Corps.

In the Air Force, he served as a financial analyst and “won an award for saving the government millions of dollars,” his sister said. As a civilian, he worked for NATO for 14 years as a cost analyst.

“He was a world traveler,” his sister said, living in many different places during his military career. “My mother, daughter, and I visited Europe with him. We went to Dachau. It was a mind-blowing experience,” she said of their trip to the former Nazi concentration camp. “When we went to the crematorium, we were all crying. It makes me choke up now.”

When Mr. Crounse returned home to Altamont, Mrs. Jones said, “He loved to reminisce about the old days with his buddies. They’d get together for backyard reunions.”

Mr. Crounse also walked his Siberian husky, Shadow, every day on Brandle Road.

Out of kindness, Mr. Crounse would take to the fields if he saw a leashed Airedale terrier, known for its excitability, approaching on the road.

Mr. Crounse had a vivid imagination and wrote a story about the life of a woman he had never met, based solely on observing the old foundation of her house along his Brandle Road dog-walking route.

“The foundation, no more than 20 feet square, is all that remains of what was no doubt a well-kept little house in times long gone by,” he wrote. “There’s a forlornness about such ruins that implores one to stop and take notice....The romantic mind (an I am without blush an incurable romantic) will speculate on its history, the people who lived there, and the events it witnessed.”

Mr. Crounse consulted an 1866 map, found the little house had belonged to “Miss Van Aernam,” and proceeded to imagine how she may have spent her days as an “old maid,” what books she may have read, whom she may have entertained.

“Did she gather strawberries in June beneath the Helderbergs with her friends, and partake in quilting bees during the winter months?” he asked “No doubt she awaited news from the front during the Civil War.”

His love of history propelled him to the Altamont Museum and Archives. He loved events at the museum, his sister said, and was cast as Dr. Fred Crounse for a Halloween event. “He wore an old silk pipe hat from our house,” said Mrs. Jones.

“Fred was the fifth Frederick Crounse, the last and most famous in the line of Frederick Crounses,” said Altamont’s mayor, James Gaughan. “He was an incredible support to our museum, giving us documents as he found them.”

The mayor went on, “I will always remember him for his extreme generosity to the village and his cultural heritage. He carried the history of the Crounses in a way the family past and present should be proud of.”

“His love of history brought him to the archives,” said Marijo Dougherty, the village’s archivist.

“Lo and behold,” Ms. Dougherty said, “he came in with the first document, all folded up.” His donation to the village, which she has authenticated and will send to a conservator to restore, is from 1784.

The paper, signed by the Dutch patroon Stephen Van Rensselaer, grants 250 acres to “Frederick the Patriot” in recognition of his heroism at the Battle of Saratoga. That is the same acreage on Brandle Road where Mr. Crounse lived and died.

“A native son, Frederick fully enjoyed his return to the land of his ancestors in his last years,” his family wrote in a tribute. “It gave him no greater joy than to live in his childhood home and on the land from which he took so much pride.”

Ms. Dougherty explained that Frederick the Patriot had provided Benedict Arnold with horses and grain, which were pivotal in winning the Saratoga battle — seen as a turning point in the American victory in the Revolutionary War.

After that first donation, Ms. Dougherty said, “Fred kept coming in with more and more things that he’d found in his house.” She called his donations “a treasure trove of documents.”

She described Mr. Crounse this way: “He was funny and extremely shy. He was a sweet, loving person.”

His sister, Pam Jones, echoed those sentiments, saying, “He was just so funny. He had a wonderful sense of humor. He was a kind, caring man.”

Endnote

One of the most stunning pieces Mr. Crounse wrote for The Enterprise involved solving the mystery of his great-grandmother’s demise. It also revealed his life’s philosophy.

“We are not born skeptics: It is something we are taught,” Mr. Crounse wrote. “The secular humanists have worked overtime to marginalize and denigrate even the ineffability of the religious experience, failing as they always do, to recognize that science may describe ‘how’ but will never answer the question ‘why.’

“I find, however, that the older I grow and the more that I learn, the more my well-programmed skepticism has become insufficient to explain the occurrence of certain events in the human experience.”

He wrote of how his great-grandmother, Lydia Truax Crounse, died in 1908, four months after the death of her husband, John Peter Crounse. Frederick Crounse sat at his computer one day in September 2008, in his Brandle Road home where portraits of his great-grandparents hang, to research the online Enterprise archives to learn how and precisely when Lydia Truax Crounse had died.

Mr. Crounse discovered a description of her visit to her son near Meadowdale that said she “was run down and instantly killed by fast train No. 7 bound east.” He cast about for the date and counted back to learn it was Sept. 27, 1908.

“Then it struck me,” Mr. Crounse wrote. “My eyes focused on the computer date on the lower right corner of my screen. It was the afternoon of Sept. 27, 2008.” Exactly one century later, to the day.

He went on, “It is difficult to describe the eeriness of the experience. Some will call this sheer coincidence, but my intuition told me that this had to be more...Was there a message for me that day?....I’ll never know the answer during this life, but, when the Grim Reaper decides that my time is up, and I enter the eternity beyond, I’ll make it a point of asking her.”

****

He is survived by his children, Elizabeth, Freddy, JP, JC, and Tim Crounse; his grandchildren, Aidan and Mia Crounse; his siblings, Mac Crounse and Pam Jones; his brother-in-law, Allen Jones; his niece, Kelly Jones; and his grandniece, Kianna Ramson.

His family thanks “all those previously mentioned for their help in so many ways” as well as his following longtime friends: Sam Bell, Paul Meineker, Gus and Char Bivona, Cindy Pollard, Joe Silvestri, Pete Brunk, Randall Crounse, Roger Whipple, Joe Kay, Marlon Webster, and Steve Marlow. “Our apologies if anyone is missing from this list,” his family wrote. “His sheer number of friends is a testament to his kind and generous nature.”

His ashes will be buried on his family’s ancestral land after the snow melts, his daughter said.

Memorial contributions may be made to the Wounded Warrior Project, Post Office Box 758517, Topeka, Kansas 66675.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer