Editorial Archives — The Altamont Enterprise, August 11, 2011

Editorial

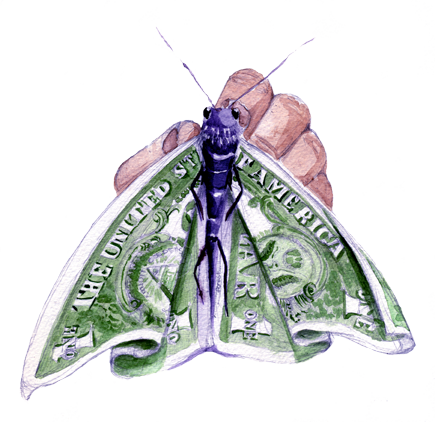

Don’t pinch pennies when the future is at stake

On Friday, kids at Farnsworth Middle School will play a small part in a large miracle. At noon, they will gather in the garden of their school’s courtyard to chant, “Gotta go, gotta go, gotta go to Mexico.” As they do so, they will release some of the Monarch butterflies they have carefully raised this summer.

On Friday, kids at Farnsworth Middle School will play a small part in a large miracle. At noon, they will gather in the garden of their school’s courtyard to chant, “Gotta go, gotta go, gotta go to Mexico.” As they do so, they will release some of the Monarch butterflies they have carefully raised this summer.

Some of the butterflies will immediately take wing, heading south for their long journey to Mexico. The bright orange butterflies with distinctive black markings will be flying to a place where they have never been, yet they know the way.

“No one knows completely how they know…It’s programmed genetically but the cues are not fully documented,” said Alan Fiero, the Farnsworth science teacher whose passion for preservation and penchant for securing grants has created and sustained the Butterfly Station.

Other of the released Monarchs will light in the garden awhile. The courtyard is filled with native plants that Farnsworth students have cultivated over the last 15 summers. In one part are plants grown from seeds that were a control group for an experiment that disintegrated with the space shuttle Columbia in 2003. The students at that time planted, from the control seeds they had harvested, a garden to memorialize the seven dead Columbia astronauts.

Those students learned a lesson more profound than the one they would have learned from growing the seeds that had gone into space. “The students understand scientists take risks because they value science and man’s quest for knowledge,” said Fiero at the time.

We’ve covered the summer project, called the Butterfly Station after a once-famous train stop in the Pine Bush, since its inception. Over the years, we’ve talked to students who felt inspired by the hands-on project to become scientists We’ve talked to others who had no intention of pursing science but learned to be confident speakers and felt proud of educating community members about an important — some would say essential — subject.

“We are providing seeds and plants to restore the Pine Bush,” Karishma Mahta told us years ago when she was just 13. The hope, she told us, was that Guilderland residents would use the plants from Farnsworth to create native gardens throughout the community.

The students who have dedicated their summers to the Butterfly Station have all been volunteers. They lead engaging free tours — Fiero estimates over 2,200 people have come through — and they also oversee a Craft Room for youngsters as well as a Museum Room where the intricacies of butterfly breeding are explored. Most importantly, they raise butterflies.

Fiero, who worked for years with his students on projects to restore the beautiful and globally rare pine bush ecosystem, dreamed of having his students raise Karner blue butterflies. The once common periwinkle blue butterfly is now on the federal list of endangered species as much of its habitat and the native lupine on which it depends were decimated by development.

Fiero’s goal was realized three years ago when Farnsworth students, working with preserve commission staff under state and federal permits, hatched 50 eggs from five Karner blue females at the school. Thirty caterpillars built their chrysalides and the emerging butterflies were released in restored Pine Bush Preserve sites.

Last year, the students, working with the New Hampshire Nature Conservancy, raised 100 caterpillars and, Fiero said, were ramped up to 300 for this year but the breeding came too late to fit into the program.

Recent releases of Karner blues raised in captivity have given environmentalists hope that the Pine Bush population may become sustainable.

The students’ work with the Monarchs has continued as well. Each of the 25 butterflies to be released on Friday will bear Monarch Watch tags as part of a program run by the University of Kansas. People finding the tagged butterflies notify the university program, which tracks the migration, producing an annual report, said Fiero.

The migratory butterflies live for seven or eight months whereas the four generations before them live only a few weeks. Guided by the sun’s orbit, the migrating Monarchs will fly about 50 miles a day towards central Mexico.

The Farnsworth butterflies that reach their destination will arrive with millions of others from the eastern and central United States and Canada to gather in a mountainous region of Mexico where they will hibernate through the winter months. Those that survive will fly from the mountains to mate in February, and then the trek northward begins again.

“We had a fantastic year,” said Fiero this week. “The kids just did a wonderful job.”

But Friday’s celebratory butterfly release will be bittersweet. For the first time since he started the summer program, Fiero doesn’t know where money for next summer will come from. He had relied on a $15,000 federal grant from Learn and Serve America that paid for everything from faculty to materials. It also funded the organic garden project at Farnsworth, where community volunteers work side by side with students, raising produce for the poor. Students at the organic garden give tours, too, stressing the importance of healthy ways to grow food.

“Funding has dried up,” said Fiero. “I’ve been searching and searching. I’ve been writing and hoping — but nothing. A lot of companies have pulled grants and, for the grants that remain, competition is much, much greater.”

We hope someone reading this will see the value of the Butterfly Station and the organic garden that teach life lessons to students and also inform the community at large. A single corporate sponsor would be an easy way to solve the dilemma.

Failing that, we urge a community effort to save these programs. The school board this past year, in working to close a $4 million budget gap, made a distinction between extracurricular activities — clubs that were more for entertainment — and co-curricular activities, like band or chorus or the student news station, that were integral to learning and served as a training ground for future careers. The Butterfly Station and the organic garden fall squarely into the latter category.

We realize, as tough times continue and as school districts now face a state-imposed tax cap, that adding funding is unlikely. Perhaps the hundreds and hundreds of residents who have toured the Butterfly Station and organic garden would be willing to pay a small fee.

This task is not as impossible as a four-inch butterfly finding its way thousands of miles to a place it has never been. We must find a way.