Editorial Archives — The Altamont Enterprise, July 14, 2011

Editorial

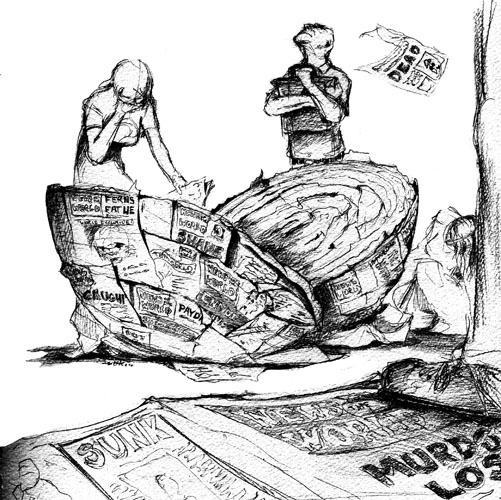

News of the World falls apart, don’t let democracy follow

“I’m a huge believer in press self-regulation because it works,” said Guy Black to a lecture  hall in Coventry, England filled mostly with American journalists. Baron Black of Brentwood is a Conservative member of the House of Lords. He is also the executive director of the Telegraph Media Group and, most importantly, he used to be the director of the Press Complaints Commission.

hall in Coventry, England filled mostly with American journalists. Baron Black of Brentwood is a Conservative member of the House of Lords. He is also the executive director of the Telegraph Media Group and, most importantly, he used to be the director of the Press Complaints Commission.

Black was speaking last Thursday, July 7, to the International Society of Weekly Newspaper Editors. The editors — we were among them — gather once a year at a conference hosted by a member; Jeremy Condliffe hosted this year’s conference.

The timing of Black’s comments was stunning. The very next day, the conservative Times of London devoted the top half of its front page to a period black-and-white photograph of Rupert Murdoch reading the News of the World. Under the picture blared the headline “Hacked to death.”

Murdoch is the media mogul who, as head of News Corp, owns both The Times of London and News of the World as well as a host of other British, Australian, Asian, and American papers and news stations. He had abruptly announced the closing of News of the World, a Sunday paper with a circulation of 7.5 million, in the wake of a scandal centering on reporters, aided by bribed police, hacking into cell phones of celebrities and most recently of the family of a murdered child.

Speculation was rampant that Murdoch had closed News of the World to keep afloat his plans to buy out BSkyB, the British Sky Broadcasting Group, the biggest pay-TV broadcaster in the United Kingdom with over 10 million subscribers. That deal fell through yesterday just before the House of Commons was to debate a motion opposing it.

Last week, at the same time that the weekly journalists were hearing from experts like Black on the Press Complaints Commission, England’s prime minister, David Cameron, was calling for an inquiry into the commission that could well end self-regulation on Fleet Street, the home of the British national press.

Great Britain has no constitution, no Bill of Rights, no First Amendment to protect its freedom of the press. “Our constitution is our history…starting with the Magna Carta,” said Bob Satchwell, an editorial member of the Press Complaints Commission. The British courts, he said, come down more on the side of privacy over freedom.

“This is probably why you got rid of us in the first place,” quipped Martin Moore, director of the Media Standards Trust, alluding to the American Revolution.

The Brits who spoke to us compared their system favorably to that in other parts of the world, France, for example, where government is involved in press regulation.

“Our product is about democracy and freedom…We can never be a regulated industry like others are,” said Black.

The British PCC had been in place since the firestorm following Princess Diana’s death, said Black. At first, he said, “It was widely assumed the British press had killed her.”

Moore held up a pocket-sized copy of the PCC code of ethics that unfolded like an accordion, meant for reporters to carry with them. “The code covers all the hotspots,” he said. “It gives us a framework that shows critics we work to a standard. These have been tested in real-life situations, with case law built up.”

For example, he said, the section on conduct in hospitals came about because journalists had dressed as doctors to sneak in and take photos of a celebrity patient.

The commission’s slogan is “Fast, Free, and Fair.” It offered a free service rather than clogging the courts with more libel cases. A board, made up of both laymen and journalists, would hear cases and, if a newspaper were found in error, it would print a correction. Last year, the PCC handled over 7,000 complaints. About 1,300 regional newspapers, 1,500 magazines, and a handful of national newspapers participated.

Black said that, in 20 years, there had never been a successful judicial review of a PCC decision.

England’s libel laws are so Draconian, said Tony Jaffa, head of the media team for Foot Anstey Solicitors, to the Americans, “You call us ‘libel terrorists.’” He described a labyrinthian no-win, no-fee system, enacted in 1999, which encourages frivolous suits and stifles freedom of expression in weeklies.

New York State’s highest court, the Court of Appeals, decided that no foreign libel judgment can be enforced unless it complies with the First Amendment, said Jaffa.

An important distinction should be drawn between the national and regional press. “It is fashionable when people say ‘the press,’ they mean one of 11 national papers with a total readership of 5 million a day. They ignore the 84 regional papers with a readership of 12 to 13 million,” said Jaffa. “The regional press abide by the PCC and take complaints seriously…The national newspapers have a completely different approach.”

He went on, “It is said the News of the World requested the greatest number of copies of the PCC code.” He quipped, “It is said…nobody ever read them.”

He concluded, “I think the PCC does a good job for those who accept the idea of self-regulation…It does work…Most people just want mistakes rectified; it keeps lawyers out and costs down.”

As we leaf through the last edition of the News of the World, which we purchased in Birmingham, England on Sunday, we can see the paper’s evolution from a rather gray, straightforward broadsheet — with headlines like “1,635 Lives Lost” for the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, or “Britain Will See it Through” for the 1939 declaration of war against Nazi Germany — to a tabloid with big pictures and screaming headlines — “Andrew and the Playgirl” in 1984, “Diana Dead” in 1997, “Named Shamed” in 2000 when, following the murder of an 8-year-old girl by a convicted pedophile, the News of the World gave names and locations of child sex offenders in Britain.

We’re grateful we can practice journalism under the First Amendment. We can take responsibility for our own mistakes and print corrections as soon as we learn of our errors.

We’re grateful, too, that our laws here make a distinction between public and private. Being New Yorkers, we regularly use both of our sunshine laws, for open meetings and freedom of information.

One of our speakers in England shared a passage from Tony Blair’s memoir in which he called Britain’s freedom of information law, passed five years ago when he was prime minister, his worst mistake. “Freedom of information: three harmless words,” he wrote. “I look at those words as I write them, and feel like shaking my head till it drops off my shoulders. You idiot. You naïve, foolish, irresponsible nincompoop.”

We see freedom of information as essential in a democracy. The 100,000 annual requests made in Britain since the law was passed show that the British people feel the same way.

We hope the current prime minister doesn’t continue in his assault on self-regulation of the media. Imposing government restraints on the press would make him worse than an irresponsible nincompoop; it would make him an oppressor.