Editorial Archives — The Altamont Enterprise, June 23, 2011

Editorial

Violence begets violence, let’s break the cycle

Sixteen years ago, we felt like there was a happy ending to a horrible story. We ran a picture on our front page of then 6-year-old Adam Croote in the loving arms of his grandmother, Linda Koerner, with the headline, “After three years, six-year-old boy reunited with kin.”

The little boy had been through unspeakable horrors. He had seen his father, Michael Croote, shoot and kill his pregnant mother, Wendy Croote. Michael Croote was an Army private, stationed in Georgia. The family, with Hilltown roots, lived in a trailer in Hinesville near the  Army base.

Army base.

Court papers showed that Michael Croote shot his wife twice in the head.

With Adam’s father convicted of murder and his mother dead, his mother’s mother, Margaret Zibura, and her husband, Frank Zibura, battled with Michael Croote’s mother, Linda Koerner, for custody of Adam.

A Georgia county court judge awarded temporary custody to Koerner, who lived in Westerlo, after hearing evidence that the Ziburas had abducted Wendy Croote and her sister, Tammy, during a custody dispute with their father, Keith Armstrong, in 1976. Tammy told the court in a notarized letter that Wendy was sexually abused by Frank Zibura during that time and that the family was unstable and constantly on the move. The girls were returned to their father after three years when a relative intervened. Both Tammy and Keith Armstrong supported Koerner’s bid for custody.

As the case was transferred to Albany County Court, and evaluations were underway for permanent custody, Adam Croote visited the Ziburas at their Owl’s Head home in Franklin county. In February 1992, they left with Adam, leaving no forwarding address. The court awarded permanent custody to Koerner shortly after.

For three years, Koerner worked with the FBI in an attempt to locate her grandson. Then in February 1995, a teacher in a school in Kansas saw a picture of Adam distributed by the National Missing and Exploited Children’s Clearinghouse. It was on top of a sheaf of construction paper. The teacher recognized Adam because he had been living in Moran, Kansas for three years with Frank and Margaret Zibura, whom he believed were his parents. They had changed their name to Kramer and called him Danny.

Adam had a new name and had to adjust to a new world. But Koerner told us back in March 1995 that he was adjusting well. He was going to school, making friends, and was overjoyed at the stream of relatives who came to welcome him, she said.

But, really there was no happy ending.

In court, as the Ziburas faced felony charges for custodial interference, their lawyer submitted letters Adam had written when he was first discovered in Kansas.

“Dear Mom and Dad,” Adam wrote, “I will miss you…I will be OK after a while…I will stop crying…I will come back.”

“Of course he was upset when they left him,” Koerner said then. “To Adam, the only people he had in the world were Margaret and Frank. That was before I arrived.”

Koerner also said that she wanted the storm of hate and revenge that surrounded Adam since the murder to stop. “He’s back. He’s safe,” she said in 1995. “Now would be the time to put things back together for his sake. Let the hate stop now.”

The horror did not stop. We lost track of Adam Croote until this week when he was thrust back into view.

After enduring the horror of seeing his father kill his mother and then of having his identity stolen, too, Adam Croote now stands accused of crimes as heinous as the one he was witness to. Croote, now 23, was arrested on Monday, accused of forcibly raping and attempting to murder a 10-year-old girl in Berne for whom he was babysitting.

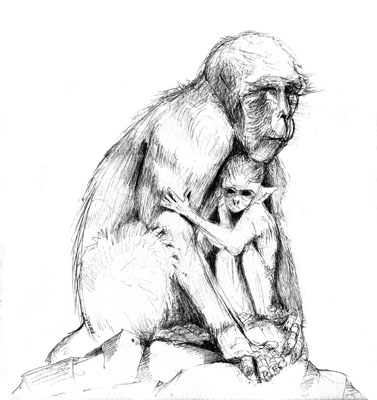

Violence begets violence. As many as 70 percent of parents who abuse their children were themselves abused while growing up, according to an article in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science. A study by a primate expert at the University of Chicago, Darius Maestipieri, detailed in the journal, looks at two generations of macaque monkeys, and concludes the pattern of abuse across generations is learned, and does not have a genetic base. Macaques who abuse their infants do so with violence, biting them, stepping on them, or dragging them around by a leg or tail.

Maestipieri took newborn female infants and cross-fostered them with mothers, about half of which were abusive. In the next generation, nine of the 16 females that were abused as infants by their biological or foster mothers turned out to be abusive towards their own offspring. Yet none of the 15 females raised by their non-abusive biological or foster mothers maltreated their offspring, including those whose biological mothers were abusers.

Nearly half of those raised by abusive mothers did not become abusers themselves. We need to learn why. We realize that humans are not monkeys, but, still, it gives us some hope that the cycle can be broken.