Editorial Archives — The Altamont Enterprise, May 5, 2011

Editorial

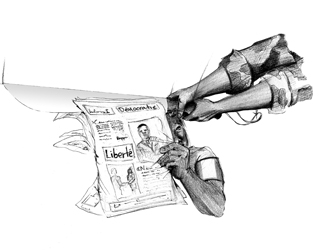

Democracy dies when the press is slashed

Art by Forest Byrd

How can we find out what is happening on the other side of the world?

We might hear from or correspond with people we know in a particular place. We might see news reports on television or read them in the newspaper or see them online.

But how reliable are these reports? And what if there is no word at all?

These questions are not academic for the Zunon family of Guilderland. Denis Zunon was born and raised in the Cote d’Ivoire in West Africa. He came to the University at Albany for graduate degrees; there he met the woman who would become his wife. Denis and Ellen Zunon spent the first 17 years of their married life happily working and raising their two children in the Cote d’Ivoire.

Then the country was torn apart by a bloody civil war. The Zunons’ plans to return to the Cote d’Ivoire have been put on hold. As violence has erupted anew in the last few months over a disputed election, the Zunons have strained to understand what is happening.

Well educated and fluent in several languages, the Zunons still struggle to find the truth.

On the day of the election, last Nov. 28, one of Dr. Zunon’s nephews called him and said, “We have been attacked.” His nephew lives in the village of Niouboua, where Dr. Zunon was raised; it served as a polling place for several outlying villages.

Dr. Zunon was told that armed rebels — outsiders, not known to the villagers — had shot and killed the gendarme who was there to oversee the voting. They wounded many villagers with machetes and burned 15 homes, including two belonging to Dr. Zunon’s uncles.

“The villagers ran into the bush,” he said; the voting was effectively ended.

On the same day, marauders in Issia — the hometown of Dr. Zunon’s mother — killed 30 people, the Zunons were told. They have been unable to make contact with Dr. Zunon’s nephews since early December.

No word for five months. That’s an unbearably long time.

The Zunons read online accounts and also read newspapers from Africa. Saturday, Dr. Zunon, opened one of the newspapers to show a photograph of an official list of numbers of voters that shows more people voted than were registered.

Dr. and Mrs. Zunon both believe that — when two government councils came up with different election results — there should have been an accurate accounting rather than a rush to military intervention.

“All those figures exist,” said Dr. Zunon.

This is not just a distant African problem. The 2000 presidential election in the United States turned on the Florida vote count. Here, the election was settled in favor of George W. Bush over Al Gore, when the U.S. Supreme Court stopped the recount ordered by the Florida Supreme Court.

Subsequently, the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago put together a group of leading national news organizations to review the ballots that hadn’t been counted by machine. The results were mixed. Had the recounts requested by Gore been completed, Bush still would have won. But the result of a statewide recount of all disputed ballots could have been different.

The courts here were dealing with problems like “hanging chads,” and other poorly constructed ballots that confused machines and voters.

The decision-makers in the Cote d’Ivoire were dealing with the far more lethal allegations of murderous attacks — like the one reported by Dr. Zunon’s nephew — to scare off voters as well as allegations of outright fraud, where vote tallies exceeded registered voters.

In both cases, though, there was a rush to judgment.

The situation in the Cote d’Ivoire was exacerbated by an already divided nation, not yet healed from a recent civil war, and also from a lack of fair and objective news coverage.

Much of the news reporting in the Cote d’Ivoire, similar to the papers in the formative years of our country, is openly one-sided, meant, at times, as a call to arms.

A dispatch posted early last month, on April 4, on the website maintained by Reporters Without Borders, states, “The fierce street fighting is being accompanied by an all-out communication and information war. We caution all the forces involved against using the media to issue messages of hate against opposing forces or civilian groups.”

In the days before, the site had chronicled the back-and-forth control of the state-owned national broadcaster Radio-Télévision Ivoirienne (RTI) as forces from each of the candidates in the contested election — Laurent Gbagbo and Alassane Ouattara — battled for control in Abidjan where Gbagbo was entrenched.

“Reporters Without Borders fears that the ongoing military battle for control of Cote d’Ivoire’s business capital, Abidjan, could be accompanied by atrocities and massacres…Amid a climate of confusion in which information is hard to confirm, Reporters Without Borders also warns against any score-settling and reprisals within the highly-polarized Ivorian media. The suspension or disruption of media activities is likely to encourage rumours and disinformation.”

Gbagbo was captured on April 11 as U.N. helicopters bombarded his arsenal in Abidjan.

On April 19, Reporters Without Borders warned against “unacceptable and disgraceful” attempts by supporters of new President Alassane Ouattara to take physical revenge on several journalists who were close to the ousted president, Gbagbo, and have been forced to go into hiding.

The site said that a hit list of eight journalists to be killed is circulating in Abidjan, including staff of the government daily Fraternité Matin, RTI, and the pro-Gbagbo media.

The offices of the pro-Gbagbo dailies, Notre Voie and Le Temps, were ransacked, their equipment destroyed and the homes of some of their journalists visited by Ouattara supporters, and these papers have not yet reappeared, the April 19 dispatch said.

“Journalists from all sides in the country’s four-month civil war have been threatened, harassed and prevented from doing their job, but for the past week Ouattara supporters have been hunting down pro-Gbagbo journalists,” the dispatch said.

Hunting down and killing journalists is wrong. So is ransacking and shutting down newspapers.

We’d like to say the world is watching. But, really, coverage of the problems in the Cote d’Ivoire in our country has taken a backseat to other news. The recent royal wedding in England received more airtime here than the war in the Cote d’Ivoire. As our own news organizations have struggled financially in recent years, foreign offices have been gutted.

It’s a shame the Zunons can’t find out the truth about what is happening in Dr. Zunon’s homeland. “There’s so much false and unclear information out there,” said Mrs. Zunon, “you don’t know what to believe.”

But, beyond that, we believe the lack of fair and in-depth coverage may have worsened the problems.

Reporters Without Borders approves of punishing those who seriously went beyond acceptable limits but is concerned about how those limits are defined.

The key here is that the new government, if it is to be credible, must be built on a foundation of justice. That means, if a journalist is to be punished, he or she must be tried in a court of law and found guilty of wrongdoing.

Having marauders ransack news offices or kill journalists on a hit list won’t further good government. To make a democracy work, the people have to be informed. That begins with good journalism.