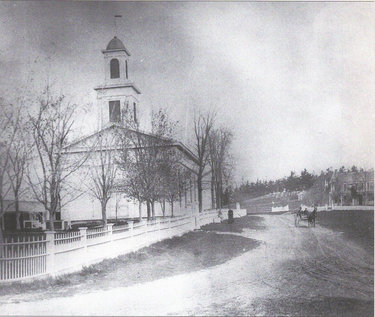

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Altamont Carriage Works employees posed with several of their carriages outside of the factory where they had been made in the newly rebuilt works after the 1886 fire. After being the site of the carriage works, the building was converted to a garage and later was repurposed as a residential building

During the second half of the 19th Century, New York State was dotted with small factories that had sprung up in both cities and small towns.

VanBenscoten & Warner’s Carriage Works, established on Knowersville’s Church Street (now Maple Avenue) was one of these enterprises, producing a variety of horse-drawn vehicles for four decades. The carriage shop was built for Henry Lockwood and William and Jacob VanBenscoten on Lockwood’s property.

After Mr. Lockwood’s death, Jacob VanBenscoten formed a partnership with Charles B. Warner, although the site of the carriage shop itself remained at the Lockwood Estate.

Proving to be a lucrative business in that era of horse-drawn transportation, their manufacture of carriages, surreys, wagons, and sleighs on site by skilled craftsmen attracted customers from many towns in Albany and other nearby counties. The shop proved such a profitable enterprise that, instead of turning out the 150 vehicles originally projected for 1885, the owners now planned to produce 200.

Knowersville’s devastating April 1886 fire wiped out several buildings, affecting a number of businesses and destroying the carriage operation at a $3,000 loss. Community members feared the reputable and successful business that provided employment for many workers would relocate elsewhere, but fortunately for the village VanBenscoten and Warner made the decision to rebuild next to its original site.

According to The Enterprise, VanBenscoten was able to buy a building site from the Lockwood Estate adjoining their original location. That November after rebuilding the 40-by-100-foot physical plant, the business began stocking the raw materials needed to begin full production in January 1887. By mid-December 1886, potential customers were being urged to contact the owners with their orders for carriages or wagons.

Such an unprecedented number of orders poured in for carriages and wagons that the carriage works resumed operation at full capacity, hardly able to keep up with the demand. Four departments had workers doing woodworking, “ironing” or attaching metal parts, trimming the upholstery and roof coverings, and painting.

With many made to order for individual customers, these vehicles offered buyers “such springs, trimmings or painted to suit your taste without extra expenses.” Other generic wagons and carriages were made to be offered in the factory repository (showroom) section to potential buyers who simply stopped in at short notice.

The carriage works’ vehicles were described in the special 1897 Enterprise feature “A Tour Among Our Business Concerns” as products that combined “lightness and strength, style and finish, superior workmanship unexcelled.”

The year 1888 brought in orders for 40 wagons, most needed for farmers’ chores or used by grocers or other businesses. In addition to their local area sales, an out-of-town “wholesale house” ordered 35 carriages. The workers had difficulty producing enough to meet the demand, enjoying the most prosperous year yet, to be followed by an even more profitable year in 1889.

Jacob VanBenscoten died in December 1889, dissolving the partnership. Charles B. Warner continued the business on alone, though Mrs. VanBenscoten seemed to be a silent partner.

An astute businessman, Warner promoted the business by exhibiting his product at a New England and New York fair held near Troy in 1892. A quotation from the Albany Evening Journal noting that his display at this fair “cannot be equaled in the quantity of goods,” was reprinted by The Enterprise.

Locally, he entered big displays at both the Cobleskill and Albany County (later Altamont) fairs. His 1894 Albany County Fair exhibit consisted of several two-horse business buggies, top buggies, open buggies, a single pleasure sleigh, a two-horse three-seated surrey, a two-horse business wagon, and a fancy baker’s wagon.

Ever the aggressive businessman, Warner opened a branch showroom in Albany at 100 State Street and a second one in Halfmoon. There is no way of knowing how successful these showrooms were or how many years they were in operation. By 1895, Warner’s annual gross was almost $75,000.

New technology

That changes in technology began to creep in during the 1890s became evident when in 1894 Warner added improved machinery with an engine and boiler to his operation. The Enterprise noted he would be able to “turn out work at a rapid rate.” High-end carriages began to be made with the innovation of rubber tires and ball-bearing axles, appealing to affluent city drivers who could drive them on cobbled streets.

Another major change came to merchandising and production when it was announced that they had just received direct from a Lansing, Michigan wagon works a car load of various types of wagons to be sold at rock bottom prices.

Potential buyers were reminded that all kinds of carriages, surreys, and road wagons were still produced totally and on short notice. Your individual order could be filled as the one of M.F. Hellenbeck who purchased a “stylish three seated sleigh, handsomely upholstered in fine broadcloth” to be used in his Altamont undertaking business and the two furniture vans for an Albany man.

Albany Mayor John Boyd Thacher ordered a two-seated surrey. From the mid-1890s on, Altamont Carriage Works would offer carloads of less expensive wagons, carriages, and sleighs made elsewhere in large factories that had the capacity to mass produce cheaper goods in addition to their own custom-made work.

The 1890s were very good years for the carriage works. That 1897 Enterprise feature on Altamont’s businesses noted, “The quality and method of doing business also serves as the best possible assurance of continued success and permanent prosperity.”

Changing hands

The partnership between Almira VanBenscoten and Charles Warner ended in 1898 when she bought him out and for a short time ran the carriage works with her son. A year later, James K. Keenholts leased the carriage factory and in 1901 sold half interest to Dayton H. Whipple.

They continued the policy of offering lower priced factory-made wagons, carriages, and sleighs, while at the same time continuing to make vehicles to order on the premises such as the blue and gold runabout with rubber tires ordered by the city of Albany for the use of Police Chief James L. Hyatt at a cost of $137.50.

Regular advertisements appeared in The Enterprise offering repairing and repainting services in addition to new horse-drawn vehicles.

Like Charles Warner before him, James Keenholts was a proactive businessman, attending an 1899 carriage and wagon workers exhibit and convention in New York City where representatives from over 300 companies. Each employing three to 35 workers, were in attendance.

As president of the Eastern Vehicles Dealers Association, James Keenholts contracted New York City’s Grand Central Palace as the site for an exhibition of finished vehicles, planned to be the biggest carriage display in the East, plus accessories needed for horse-drawn vehicles, all for their convention.

“The Automobile Habit”

Did either Mr. Keenholts or Mr. Whipple happen to read page 3 in the May 4, 1900 issue of The Enterprise where a brief article appeared titled “The Automobile Habit,” which had been reprinted from The Washington Post?

Telling the story of United States Senator Wolcott of Colorado, an automobile enthusiast who drove an electric car powered by battery, the paper said he believed not only had the automobile come to stay, but “it will increase and multiply until the carriage drawn by horses is relegated into oblivion.”

On the following page, Keenholts and Whipple’s ad was urging people to get their wagons and carriages repaired or repainted at the Altamont Carriage Works. They also advertised in the Albany Argus that they were “manufacturers and dealers in fine carriages and sleighs whose specialties were Helderberg buckboards, physicians’ wagons and open road wagons.”

By the middle of that decade, it must have become obvious that owning a carriage factory was financial woe in the making.

Not only had carriage manufacturing been taken over by large factories in other parts of the country using machines for the manufacturing process to mass produce stock, but more and more attention was being paid to the automobile which was mentioned with increasing frequency in newspapers.

Already in 1905, the New York State Fair was promoting a day set aside as “Automobile Day.” A year later, the Enterprise news notes about local doings began to mention local people who actually had purchased automobiles.

The year 1908 marked the development of the Model T and once prices of cars came down to middle-class levels, there was no holding folks back.

But, in those early years of auto ownership, winter driving in upstate New York was impossible and for a few months it was back to horse-drawn equipages. Keenholts and Whipple were well aware of the automotive trend and diversified their offerings by beginning to carry a line of farm machinery and gasoline engines.

That year, the two announced they would be the agency for an automobile they would have on exhibit in their repository called the “Farmers’ Automobiles,” advertised as being fit for rural roads and at a low price besides. Two months later, their fair exhibit included carriages and wagons, but it seems their attempt as automobile dealers failed seeing nothing was heard of the car again.

Next, local competition began when Sands’ Sons, another pair of active Altamont businessmen, began advertising a variety of automobiles with the slogan, “The automobile is here to stay.”

In spite of the excitement over this new speedy conveyance, people were still buying carriages and wagons from the Altamont Carriage Works, their names listed among local news items. However, Keenholts & Whipple were hedging their bets and advertised heavily their farm equipment to take up the slack.

In 1909, they were optimistic enough to receive five carloads of wagons, carriages, and farm implements, much of which was to be on display at the Altamont Fair. The next year, the Altamont Carriage Works set up the usual display of wagons, carriages, and farm implements, but nearby Sands’ Sons showed “the celebrated Brush and White Steamer automobiles.”

James Keenholts died early in 1912 and, as of March 1, the proprietors of the Altamont Carriage Works became Dayton H. Whipple and Son. Although they continued to retail wagons and sleighs, the added services of painting and repairs of both horse-drawn vehicles and automobiles were also available. Case farm equipment and gasoline engines were also part of their inventory.

The years 1913 and 1914 brought few Carriage Works’ ads in the Enterprise, while in 1915 a “Notice to Farmers” appeared that the Altamont Carriage Works had established a catalogue system: If you hadn’t received your catalog in the mail, let them know.

Wagons and farm implements continued to feature in their inventory, but they also carried auto and machine oils and could repair all makes of automobiles.

The final blow fell the next year when Della Keenholts, the actual owner of the property, sold the premises for $3,500 to Morton Makely who planned to establish a modern garage and machine shop there.

The Whipples moved over to Park Row to continue their business, mainly farm equipment. The last time the words Altamont Carriage Works appeared in an ad was March 1917 from their new location.

After this time, their ads simply read “D.H. Whipple and Son” and the carriage works passed into history along with the carriages, wagons, and sleighs.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

A group of Helderberg Church women of varying ages met at a private home in Fullers probably to plan a church fundraiser, but also offer each other support if needed. Women’s health issues were rarely mentioned in public except in the Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound advertising.

When in 1908 William Thomas Beebe passed away at the advanced age of 94, he had achieved twice the 47 years average age at death reached by the ordinary American at the turn of the 20th Century.

While few Guilderland residents lived to Beebe’s advanced years, an informal survey of the Enterprise’s local columns and obituaries appearing during the century’s first decade reveals that, while only a rare few ever reached 90, a very sizable number of townspeople survived well beyond 47 into their 60s, 70s and 80s.

To reach elderly years, each individual had to avoid or overcome many possibilities of serious or possibly fatal illness from infancy to old age. This was still a time when health care was entirely provided in the home where women were the primary caregivers.

Professional medical aid was available from Guilderland’s dedicated doctors traveling for house calls in buggies or sleighs: McKownville’s Dr. Helme, Guilderland’s Dr. DeGraffe, Guilderland Center’s Dr. Hurst, Altamont’s Dr. Jesse Crounse and Dr. Fred Crounse. In addition, Voorheesville’s Drs. Shaw and Joslin crossed town lines to treat some patients here as well.

Tending to births and babies, children, severe illnesses, accidents and deaths, they were limited by the preliminary medical knowledge achieved up to this time. Guilderland’s location made trips to either of Albany’s two hospitals practical to undergo the limited surgeries then already possible and quite a number of residents were reported to have undergone operations.

Then, as now, finances played a part. Even though country doctors had the reputation of being flexible about payments and were reputed to accept payment in farm products or services at times, a poor family would likely hold off calling the doctor until things were critical while hospital visits would have been very unlikely unless the patient could pay.

Holding out hope of relief or cures were the endless Enterprise ads for patent medicines that seemed to cure or address almost any health problem, various nostrums for sale at the town’s general stores or available by mail. Sick citizens of that era, often ardent prohibitionists, were unaware that these concoctions were often heavily laced with alcohol or narcotics.

Ads frequently carried testimonials of cures that with clever merchandising usually mentioned multiple bottles were needed to achieve that particular cure or at least relief. Consumers’ choices included Cramer’s Kidney and Liver Cure; Chamberlain’s Colic, Cholera and Diarrhea Remedy; Dr. Miles Heart Cure; Dr. Miles Nervine; and Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp Root for bladder problems — just a few samples of what were advertised.

An informal survey of Enterprise local columns from the first decade of the 20th Century gives much detail about the state of health in Guilderland. Some of the reporting seems an invasion of privacy, but these reports probably brought sympathy, support, and actual help for the families or individuals involved.

Childhood illness

Babies were born at home, mothers often attended by one of the local doctors. Stories have been passed down of premature babies put in slightly warmed ovens to survive if possible.

Living through infancy was a challenge for a child with a congenital birth defect or any digestive issues and most infant deaths were attributed to cholera infantum, a general term relating to this failure to absorb nutrition. Cholera infantum shows up on the Prospect Hill Cemetery record of infants’ burials during that period.

Poignant notices occasionally appeared such as this one in the Guilderland Center column referring to the couple whose infant daughter “died after gladdening the hearts of the young parents for two days” or another grieving couple who had “the sympathy of their friends at the loss of their infant daughter, aged seven months.”

Having passed through infancy, childhood was the individual’s next challenge when bouts of viral childhood diseases would be their lot. Being that the town’s one-room schools used a pail and dipper and an outhouse to be shared by all, when the contagious childhood diseases of measles, mumps, and chicken pox showed up, they could easily spread and every now and then one or another of the town’s schools would be closed for a week due to illness.

More serious were the contagious bacterial childhood diseases of whooping cough and scarlet fever. During this decade, whooping cough appeared rarely in Guilderland, but scarlet fever showed up repeatedly year after year. Caused by streptococcus, these two diseases could be fatal and there were examples of deaths here in Guilderland.

One year, Parkers Corners District one-room school closed for a week due to scarlet fever. One family there first lost their 16-year-old daughter to the disease, but within that month their 4-year-old daughter who had initially come down with scarlet fever, developed the complication of pneumonia and died as well.

Another year, a young man from the Fullers area died of “malignant scarlet fever,” while near Altamont a 47-year-old man died described as “a cripple nearly all of his life from the effects of scarlet fever.” A serious complication that could result from scarlet fever was rheumatic fever affecting the heart.

Diphtheria was another bacterial disease chiefly of childhood, but adults could catch it as well. It was frequently fatal. Although not widely reported in Guilderland during these years, there were two deaths from diphtheria listed among Guilderland children buried in Prospect Hill Cemetery at this time.

Children were forced to confront death at an early age at a time when it was not unusual for a classmate or a sibling to die. On the day the funeral of one 9-year-old girl, “loved by all who knew her,” was held from her father’s home near Fullers, the one-room school she attended was closed and the teacher and students attended the funeral.

Adult sicknesses

Assuming a man or woman had survived infancy and childhood, there were many possibilities for sickness or ill health during the adult years. Chronic diseases such as high blood pressure or Type 2 diabetes were left untreated with no medications available.

Eventually a sufferer of hypertension would likely have died of apoplexy or stroke, usually people of more advanced years, with many recorded by those diligent community reporters. Diabetes was not mentioned possibly because childhood diabetes was probably fatal and adult diabetes was rare at that time due to their way of living.

People suffered from kidney disease with Bright’s disease and nephritis mentioned. Consumption or tuberculosis did not seem to be a problem here and, although one man died of it, he seemed to have moved to Guilderland more recently.

Quinsy, a throat infection, appeared every now and then although tonsillitis was more common. Also frequently noted was appendicitis and several had surgeries at one of Albany’s two hospitals.

Typhoid fever, a serious bacterial illness acquired from drinking contaminated water, could be fatal and was always serious. Mentioned regularly, most survived, but a 24-year-old man “of good habits and disposition” died after a bout with “malignant typhoid” and a 16-year-old Guilderland girl did not survive after she became ill.

One seasonal malady was la grippe or the grip known now as influenza or flu. It appeared each year, affecting some who recovered quickly and returned to work, while others were housebound for varying periods of time. For those already suffering health problems, fatal pneumonia could develop.

Cancer, always a dreaded diagnosis, was not as openly discussed in that era as in our own. Nevertheless, it was many times mentioned as a cause of death.

Some of the surgeries at the Albany hospitals were cancer-related such as the Guilderland Center man who “had an operation for removal of a cancer from his lower lip. Drs. Frank Hurst and Frederick Crounse were the physicians in attendance.”

In spite of the operation, although being called a success, he was back a month later for “the removal of another cancer of the same nature.” Sadly, a year later the disease killed him and sympathy was asked for his grieving family.

A Settles Hill woman died from “the dread disease cancer,” while another woman had “looked forward to a time when the ravages of cancer would end all her suffering and she could sleep in death.”

Others who were noted as dying after a lingering illness or suffering for a length of time may very well have also died due to cancer. However, most of these cancer sufferers seemed to have reached their 50s and 60s.

In 1900, there was a smallpox scare when the writer of the Village & Town column wrote that several cases of smallpox had recently been reported in Schenectady where there had been precautions and quarantines in place with vaccinations being urged.

“It would be well for the inhabitants of this and nearby villages to consider the matter of vaccination before the disease makes its appearance,” the village corresponded advised

The next week, the Guilderland Center correspondent commented, “No small pox developments as yet, still many are calling on the doctor for vaccination ….” Smallpox never materialized in Guilderland to the relief of the town’s doctors.

Women’s health issues were still unmentionable in those closing years of Victorian era prudery. However, the frequent ads for Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound actually were often quite frank and women with “female problems” were urged to write to Mrs. Pinkham for advice after being assured all letters were “received and opened, read and answered by women only.”

And of course, women were urged to buy bottles of Vegetable Compound in the meantime.

Accidents

Accidents, frequently serious enough to require a doctor’s attention, often related to wagons or farm chores. Try doing your farm chores with your “right hand injured quite severely by a hay hook striking into it” or after you cut your “arm quite seriously while splitting wood.”

One laboring man in Altamont “had the misfortune to break his wrist [when] thrown off the coal wagon. The injury will lay him up for some time. Depending on his day’s work, the misfortune is the more severe.”

A week later, it was noted he had no use of his arm.

In addition to being unable to do necessary work, cuts or scratches received on the job or farm could lead to blood poisoning or sepsis. Dr. Fred Crounse was caring for a man’s case of blood poisoning resulting from “a sore on his little finger,” one of many examples reported during these years.

And accidents could be fatal. One unfortunate man lost his life crossing the West Shore Railroad tracks in Guilderland Center, and a Meadowdale woman was hit by a D&H train while walking along the tracks.

With the odds against them, how did so many of Guilderland’s population reach ages well beyond the average of the nation’s general population? Low population density, fresh air, pure water, local sources of nutritious food, and a lifetime of hard work all played a part.

Having good genes was always an advantage as well. In addition, the ministrations of dedicated and obviously skillful country doctors contributed. And for those who could afford it, the possibility of treatment at either Albany Hospital or Albany Homeopathic Hospital (now Memorial Hospital) extended some lives as well.

Modern Americans take for granted antibiotics, medications to treat a myriad of chronic diseases and conditions, scans, advanced surgeries and vaccines. Medical research and development has taken us a long way in the past century and a quarter, allowing most Americans today to live to 79.1 years or more on average.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

The Fullers District 13 School continued in use until Guilderland School District centralized and Fullers students began attending Altamont Elementary School. In 1953, the district auctioned off the old building, receiving $1,200 from a buyer who converted the school into a residence. It still stands on the north side of Route 20.

Many years ago, I was put in touch with an Arizona man who had spent his boyhood years in Fullers. During many phone calls as Ed LeViness reminisced about his youth during those Depression times leading to the early World War II years, I jotted notes. With his permission, I wrote this story about his boyhood years in Fullers.

Fullers had once been a prosperous little 19th-Century farming community with its own post office, general store, and railroad depot located on the Western Turnpike where it was crossed at grade level by the West Shore Railroad (now CSX). By the 1930s, the businesses and depot had disappeared with the tracks now crossing overhead by trestle.

However, the people living there continued to feel a sense of community, chiefly because their small one-room District No. 13 Fullers School continued to give the area its identity.

Just as the Depression began in 1929, the LeViness family: Jack, Ruth, and their 4-year-old son, Edward, accompanied by Edward’s Chesbro grandparents, moved into a house (now taken down) on Route 20 in Fullers. Upstairs the discovery of phone books from several Midwestern cities led Jack LeViness to suspect the place might earlier have been a speakeasy.

With the house came 180 to 200 acres of pastures and hayfields and a barn. The family milked 20 dairy cows, grew silage corn, and cut acres of hay. Earl Gray, a Dunnsville man, would come around with his hay press, a device that used actual horse power to compress hay into bales.

There were several other active farms along Route 20 in that area, including the Van Patten farm just west of the railroad tracks (where 84 Lumber is today) with the barns across Route 20. The Coss farm, located at the corner of Fuller Station Road and Route 20, was also divided by Route 20. The Coss farmhouse was the old Fullers Tavern (also taken down now).

Milking cows by hand was still the rule in those days. The large 40-gallon metal cans containing milk were placed daily on a wooden platform at the edge of the road waiting to be collected by the milk truck that at the same time left off freshly washed cans from the day before.

Some of the more affluent farmers in Guilderland were using tractors, but many including the LeVinesses continued to rely on horses. Behind their house was a chicken coop with registered New Hampshire red hens producing high-quality eggs that were sold locally.

As Ed grew older, he was expected to do all sorts of chores, regularly milking cows and cleaning out the henhouse. His mother and grandmother canned large quantities of fruits and vegetables for the family.

Accumulating enough income to support a family was no easy matter during those Depression years. In addition to earnings from farming activities, Jack LeViness worked at General electric in Schenectady, but had had his hours cut back to two days a week.

Until he retired, Mr. Chesbro was a West Shore engineer. Ruth LeViness and her mother added to the family finances by hanging a sign out front of the house with the inviting name “Sunny Croft,” earning spare cash from tourists or boarders.

Owning a car was a necessity for any family residing in Fullers. An older model Durant that needed to be cranked to start was the car that brought the LeViness family to Fullers. Later, the family moved up to a Hudson Terraplane, produced between 1932 and 1938, “inexpensive, but powerful,” and by 1941 Jack LeViness was able to purchase a new Chevrolet two-door sedan.

About once every two weeks, the family drove to Altamont to shop at the A & P, and there were weekly trips over to Guilderland Center to worship at the Helderberg Reformed Church where Ed attended Sunday School.

Moderate traffic rolled over U.S. Route 20, the old turnpike having become a two-lane paved highway that was a main route west. A few farmers could still be seen out in horse-drawn wagons, giving Tommy Croote’s blacksmith shop on Fullers Station Road steady business.

Ed was just old enough to recall the old covered bridge at Frenchs Hollow being taken down in 1932 to be replaced by a new two-lane bridge. A weathered railroad-crossing sign remained along the road even though it had been a long time since anyone had to worry about tangling with a train on a grade level crossing in Fullers.

Passing motorists could stop for a dollar’s worth of gas at Oliver Cutler’s Socony gas station on the southeast corner of Fuller Station Road and Route 20. At the antiquated gas pumps, it was necessary to push a handle up and down for gas to fill a glass cylinder at the top, gravity allowing the gasoline to flow into a car’s gas tank.

Every now and then, men of the neighborhood gathered at the gas station for a friendly game of penny ante cards. Each player contributed a small amount of money for the pot and used matchsticks to keep track of the winner of each hand, allowing whoever ended up with the biggest pile of matchsticks to take home the pot.

Adventures

In addition to chores and school, Ed had fun and exciting adventures with several boys his own age. He remembered his bike carried him down Fullers Station Road and Frenchs Hollow Road to Cain’s farm where there was a field used by the kids to play baseball or to the Normanskill where there was a great spot just below the falls for a cooling swim.

Winter brought sleigh riding either on hilly Fullers Station Road or Frenchs Hollow Road leading down to the Normanskill. Most challenging was the steep hill on the north side of the Normanskill where French’s Hollow Road sharply curved just before going over the bridge.

One time, a family acquaintance took Ed up in an antique biplane with two open cockpits and double wings on a flight over the local area, beginning Ed’s lifelong love of flying.

As the boys got older, muskrat trapping helped to earn some much-needed cash. Ed found the best spot to catch muskrats was along the Normanskill near the footings of the railroad trestle.

By state law, trappers had to check traps daily, a serious responsibility for a boy, who then had to skin any muskrats he caught, preparing the pelts to be shipped to a fur wholesaler. Ed received a Remington .22 for his 11th birthday, a gift he prized all of his life.

Honing his marksmanship skills by taking out woodchucks on nearby farms, Ed found local farmers were delighted to be rid of the rodents whose deep holes created a serious menace in their fields.

Not all pleasures were found in the neighborhood. Radio provided all ages with information and entertainment from afar.

An Atwater Kent radio on legs sat in the LeViness living room where Ed sat listening to shows like “Tom Mix Ralston Straight Shooter,” “Fibber McGee and Molly,” and “One Man’s Family.”

About once a month, the LeViness family drove to Schenectady to see movies, usually at the State Theatre, but sometimes splurged on admission to the more expensive Proctor’s where the program not only included a movie, but also vaudeville or a big band. The movie of his childhood that made the biggest impression on Ed was “Gone With The Wind.”

School days

Windswept, open farm fields surrounded the Fullers one-room school on Route 20. In cold weather, a potbelly stove was fired up, first with kindling and, when that blazed up, coal was added. An active parent-teacher association was involved with the school whose members brought in hot soup at lunchtime during cold winter days.

Ed walked each day to school. A bright boy, he was placed in second grade almost immediately.

He had fond memories of Miss Isla Heath, the teacher who not only taught the basics to all eight grades, but enriched the children’s lives by taking them on nature walks, encouraging them to act in plays, and to be patriotic and kind.

Ed was once the recipient of a birthday-card shower from his fellow classmates on the occasion of his 10th birthday when he was housebound recuperating from injuries caused when he was hit by a car.

Miss Heath was expected to coolly handle crises as well. One winter’s day, the snow was good for packing. At recess, the kids were having a great time lobbing snowballs at each other over the schoolhouse roof.

Ed made the error of peeping around the corner of the school building only to see a frozen missile coming straight at him. Quickly pulling back, he hit his head on the building’s sharp corner, cracked open his scalp, and immediately began to bleed profusely.

Miss Heath performed emergency first aid, piled him into her Ford coupe, and then raced up Route 20 to deliver Ed to his mother. Eighty years later, Ed still had the scar!

The children looked forward to two holidays as welcome breaks in the routine. At Halloween, ducking for apples was the highlight because Miss Heath stuck a nickel inside of one apple.

With one apple for each student floating in a water-filled wash basin, one by one, the students began to duck down to retrieve an apple, each child hoping they would go home with that precious nickel, which in the 1930s bought an awesome amount of candy.

At Christmas, there was always a decorated Christmas tree and students performing in a play put on for the whole community one evening just before the holiday. Mothers had made costumes and Miss Heath rigged up a stage curtain of sorts for the performance. Santa showed up and there were refreshments and a wonderful time was had by all.

Boys’ and girls’ 4-H clubs provided both practical and social activities for Fullers’ young folks. Ed’s parents were each leaders and even Miss Heath helped out with the girls’ group.

Both groups had hands-on projects and exhibited at the Altamont Fair each year. Building birdhouses was an example of one of the boys’ projects.

Meetings were at various members’ homes where refreshments were a treat often followed by recreational activities such as one winter’s night when the boys went coasting after their meeting.

Members learned social skills as well. After one meeting of parents and teachers at the school, 4-H members displayed their finished projects and then served refreshments to the adults who attended.

Often, activities were co-ed. Once there was a ski party followed by refreshments and every now and then a joint activity with another 4-H group such as the roller-skating party the Berne-Knox 4-H invited them to attend.

One year, Ed attended 4-H camp at Kinderhook Lake and attended Albany County 4-H Council meetings. Having been named to the 4-H honor roll, Ed was invited to dine at Albany’s Ten Eyck Hotel at a Kiwanis luncheon.

To earn an eighth-grade diploma, the New York State Education Department requirement was to pass seventh- and eighth-grade Regents exams in basic subjects. If all seventh-grade Regents were passed in seventh-grade, the student was allowed to move directly on to high school.

Ed was one of those pupils who qualified for high school without sitting through eighth grade, joining the other high school students from the Fullers, Parkers Corners, and Dunnsville Common School districts who attended Draper High School in Rotterdam.

The three local districts paid tuition to Draper and provided transportation by Bohl Bros. Bus Co. of Guilderland. Ed had no trouble making the transition from the one-room country school to Draper, graduating in the class of 1943.

War years

For high school students in the early 1940s, the future was ominous as the Second World War raged in both the Pacific and in Europe.

At graduation time, Ed, Raymond Bradt, and Vard Armstrong, two of his childhood friends from Fullers, traveled to downtown Albany to enlist in the Marines.

Because Ed had skipped elementary grades, he was only 16 and was told to return when he was 17, have his father sign the permission papers for an early enlistment, and then come back down to the recruiting station, which he did.

His friends who were already 17 were able to enlist once their fathers had signed the papers. Ironically, it was Ed who was actually called first. He fought in the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa with the 5th Marine Division.

All three returned home safely.

As Ed remembered, others of his generation who served from Fullers were Jacob Bradt and Robert Croote in the Navy; Emerson Van Patten in the Army Air Corps; and Anna Croote in the Women’s Army Corps, Margaret Culver in the Marines.

Morris Becker, who served in the Army, was wounded in Germany and Frank Pospicil, a Marine, was killed at Iwo Jima.

At Union Station, Ed’s parents waved goodbye to him as he boarded the train bound for Parris Island, his idyllic Fullers boyhood behind him forever.

****

Edward Arthur LeViness died on Dec. 7, 2017 at the age of 92. He returned home after World War II but then served again during the Korean War, and was honorably discharged in 1952 after which, according to his obituary, he quickly moved to Arizona where he worked as a cowboy, before attending the University of Arizona on the GI bill, earning a master’s degree in biology. Married with three daughters, he worked for three decades for the University of Arizona as a range and livestock specialist, helping cattle ranchers around the state.

One mid-September morning in 1863, most Knowersville residents headed up the original Schoharie Road to stand beside the shiny newly laid tracks of the Albany & Susquehanna Railroad, eagerly watching for the first passenger train to come rolling through.

Their busy, prosperous little hamlet almost a mile down the road, depended on the traffic of the Schoharie Plank Road, horse-drawn traffic that would quickly be replaced by that advance in travel technology, the railroad.

First incorporated on April 19, 1851 as a rail line to connect Albany and Binghamton and link up with the Erie Railroad, Albany & Susquehanna got off to a slow start due to lack of funds complicated by expensive construction costs. Eventually the New York State Legislature came through with a government loan to complete the project.

Beginning in Albany, the proposed route cut through the towns of Bethlehem, New Scotland, and Guilderland through a sparsely populated farming area of town where what became modern-day Meadowdale and Altamont were on the route. Topographical obstacles caused delays, adding expense to the project.

It was necessary to build a grade of 70 feet per mile for two-and-a-half miles from Albany through the valley of the Normanskill where ravines created by tributaries had to be bridged. The route then crossed a plain until it entered the Bozenkill valley just past Knowersville. Beyond this, the tracks climbed another grade of 70 feet per mile for four miles with two very high embankments to be erected along the way.

Once construction was underway, the leading Albany newspapers began printing frequent updates on the railroad’s progress. In May 1862, the Albany Evening Journal reported that a telegraph company was placing poles along the roadbed of the railroad.

By June, the section of track within Albany city limits was to be laid to connect with rails already laid to Duanesburg. However, the Dec. 18, 1862 Albany Argus noted that, by Jan. 1, 1863, it was expected that the rail-laying would be completed from Albany to the Knowersville crossing of the Schoharie and Albany Plank Road (where the tracks cross Route 146 today).

Obviously, construction took longer to reach Duanesburg than predicted earlier in the year. The Albany Argus noted that the railroad company’s rolling stock consisted of three locomotives, about 10 freight cars, several “dirt” cars, and three or four passenger cars.

Excitement was growing as frequent news of the railroad’s progress appeared during the summer of 1863. By July, it was reported all the track work within Albany city limits was complete with a depot on Broadway at Church and Lydius Streets, a location approximately where the later D & H building stood.

In mid-August, there was a dry-run excursion train carrying stockholders and their friends who were given complimentary tickets. Leaving at 9 a.m., they set off for the “once secluded and quiet village of Schoharie.”

The Albany Evening Journal predicted the trip would be a “pleasant jaunt over a section of country that has been comparatively but little traveled.” By 5 p.m., they were back in Albany. The previous day, the first freight train had rolled through on its way to deliver goods to B.F. Wood in Esperance.

Formal opening

Finally, the big day of the formal opening of the Albany & Susquehanna arrived: Sept. 15, 1863. There must have been such a clamor for tickets to take part in the official excursion that on Sept. 12 the Albany Evening Journal was requested to announce that, because of the limited number of passenger cars, it was impossible to accommodate all who wanted to take part.

Two-hundred people including Governor Horatio Seymour, Albany’s Mayor Eli Perry and the Albany City Council members joined the Albany and Susquehanna Directors on board the special trains.

“Elegantly festooned with wreaths and bouquets of flowers by the tasteful hand of the lady of the President of the Road and the daughter of Mr. Spencer, one of the Engineers of the Road,” the wood-burning locomotives must have been a sight to behold as it chugged through Knowersville.

All along the way, enthusiastic onlookers gathered. The Evening Journal made special mention of the welcome from the citizens of Knowersville and Esperance who greeted the bedecked trains with cheers and salvos of artillery.

The people of Quaker Street, outside of Duanesburg, constructed two arches of evergreens decorated with flowers. When several hundred school students along the way greeted the train with cheers, Governor Seymour had the train halted two or three times to speak to the children.

Many decades later, Guilderland Town Historian Arthur Gregg, in writing about the Albany & Susquehanna Railroad, quoted “Webb” Whipple, an elderly man who grew up in old Knowersville. He regaled Gregg with tales of his encounters in the 1860s, including his description of the Albany & Susquehanna.

Whipple recounted, “Me and another fellow played hooky the day the first train went through from Albany to Central Bridge. We made up our minds to do it though we knew just what we’d get when we got home. And we did get it, too.

“Besides the engine, that train was made up of flat cars with seats bolted down crossways. When it got here it was crowded with fine dressed men and women from New York and Albany. That didn‘t bother us none though. We climbed right on board.

“Most everybody on the train had brought picnic lunches and we got ourselves invited. We weren’t at all bashful and stepped right up when we was asked. It was a great trip and I wouldn’t have missed it for anything, lickin’ or no lickin’.”

There is no way to verify Whipple’s account, but Gregg took him seriously, quoting Whipple in several of his articles.

In 1863, the end of the railroad line had reached only as far as Central Bridge. When the excursion arrived there, the travelers enjoyed a catered lunch spread out in a nearby grove followed by lengthy speeches ,which took up many inches of column space in the next day’s Evening Journal.

Shortly after four o’clock, the trains left to return to Albany, “nothing having occurred during the day to mar the pleasantness of the excursion.”

Regular traffic

Within a week, it was reported that an average of 100 passengers were on trains arriving or leaving Albany, giving the company $100 per trip. In addition to this was income from freight traffic.

The Evening Journal forecast that, once there were two trains a day between Albany and Central Bridge, “We shall see plenty of the crinoline portion of that once sequestered region coming down here regularly to do their shopping and sightseeing.”

A notice placed in the June 23, 1864 Schoharie Unionist newspaper by M.F. Prentice, president of the Albany & Susquehanna, announced the following schedule for the two trains running between Albany and Schoharie:

The first train for passengers and express freight would leave Albany at 7:15 a.m. and arrive in Schoharie at 8:50 a.m. It would return to Albany leaving Schoharie at 9:30 a.m., arriving back to the city at 11:30 am.

The second train for passengers and freight would depart Albany at 2 p.m. and arrive in Schoharie at 4 p.m. while returning from Schoharie at 5:15 p.m. and arrive back in Albany at 7:30 p.m.

The locomotives were wood-burning and according to “Webb” Whipple’s recollection, as time went on the prices on cords of wood were driven up as high as $16 in the area.

Center shifts

When the trains began arriving at Knowersville in the autumn of 1863, there wasn’t much to be seen.

The Severson family’s Wayside Inn (now the site of Stewart’s in Altamont) had been put out of business when the Schoharie Plank Road opened in 1849, relocating traffic a half-mile away following a route less taxing to horses than straight up the escarpment as it had been near Severson Tavern.

While some along the way had objected to the railroad coming through their property, the Seversons were happy to give a right-of-way across their farm.

Within four years of the railroad’s opening, George Severson had built Severson House, a hotel across the tracks from the small depot that the Albany & Susquehanna had erected for the Knowersville stop.

The Severson farm and others nearby were divided into valuable building lots. A building boom began in the vicinity of the tracks with many homes and businesses going up in the next few years.

The original Knowerville, east of present day Gun Club Road, became a quiet neighborhood known as the “old village” in later years. The Knowersville post office was soon moved to the new center of population. Once the railroad began operations, the Plank Road Company quickly went out of business.

The Susquehanna & Albany was finally completed to Binghamton in l869. The late historian Arthur Gregg wrote of seeing a small yellow card on which was a timetable for the route from Albany to Binghamton, showing five trains running daily in each direction.

A train leaving Albany at 7 a.m. reached Knowersville at 8:12 a.m. This train reached Binghamton at 7 p.m. after having stopped at every tiny station along the line. In Guilderland, there was another stop called “Guilderland,” eventually renamed Guilderland Station when a post office opened there, later renamed Meadowdale.

“Railroad Wars”

In spite of being a minor railroad, the Albany & Susquehanna became part of America’s railroad history.

It had been decided back in the 1850s, when the railroad was in the planning stages, to lay the tracks with a 6-foot gauge (that is, with 6 feet between the rails) probably with the intention of linking up with the Erie Railroad also laid with a 6-foot gauge unlike most other larger northern railroads which had a 4 foot, 8.5 inch gauge.

The Erie connected Jersey City with Buffalo and in 1869 was under the control of majority stockholders Jay Gould and Jim Fiske, two financiers with shady reputations, who were manipulators of railroad stock.

Realizing the Albany & Susquehanna would link the Erie and the coal fields of Pennsylvania with the rapidly industrializing Northeast, they began to scheme to capture majority interest in the stock through stock manipulation, court cases, and even violence between Erie crews and Albany & Susquehanna workers.

While the original stockholders centered in Albany struggled to keep control, there were endless court cases eventually deciding for the original local stockholders. Finally, in 1870, the conflict over control had come to an end with the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company leasing the Albany & Susquehanna, eventually changing its name to the Delaware & Hudson Railroad.

Locally, the obscure Susquehanna & Albany Railroad played a huge role in Altamont’s history when the village developed around the small depot erected by the railroad company in 1864 on what had been empty farmland.

The easy accessibility to the outside world helped to make it an especially prosperous village.

Nationally, the conflict between the original shareholders and the two robber barons has acquired the name “Railroad Wars” and has put the otherwise obscure Albany & Susquehanna into any history of 19th-Century railroading in the United States.

William Crounse was among the numerous Guilderland volunteers who answered the call to fight for the Union during the Civil War.

Published in Albany in 1866 shortly after the war’s end was a volume entitled “The Heroes of Albany: A Memorial of the Patriot — Martyrs of The City and County of Albany.” Its author, the Reverend Rufus Clark, had written a series of brief sketches about local men who perished in the conflict, describing their early lives, their war experiences, and the circumstances of their deaths.

Sadly, Guilderland’s William Crounse was among the heroes he eulogized.

Clark characterized Crounse as a typical country lad growing up on the farm owned by his father, Abraham Crounse, probably the “A. Crounse” appearing on the 1866 Beers Map in the vicinity of Gardner Road.

Born in 1830, one of four sons, he grew up on the family farm. William Crounse’s pious mother was influential in forming his character and he reciprocated by having great love for his parents. At 21, he married, continuing to help manage his father’s farm. In 1855, William Crounse moved to Albany, joining his brother in business.

With the outbreak of the rebellion, William Crounse was determined to serve his country. Mustering into the 177th Regiment New York State Volunteers in October 1862, he was one of several Guilderland men who had also joined this regiment, spending two months training with them at Albany.

In December 1862, Crounse departed with his regiment, sailing in an overcrowded ship to New Orleans. His health had been so poor that his friends attempted to persuade him to apply for a discharge before the regiment left Albany, but he persisted, replying to their concern, “My country needs every man she can get, and it is my duty to assist all I can.”

On their arrival at New Orleans, the soldiers in the 177th were assigned to help reinforce the defenses around the city. When he reached camp at Bonnet Carre up the Mississippi from New Orleans, Crounse’s health had improved enough for him to be promoted to the rank of orderly sergeant and detailed to duty as assistant provost marshall.

Although William Crounse did not profess any particular religious denomination, he regularly attended divine service in camp, keeping apart from “the vices and abuses, which from a social and lively temperament, he was particularly exposed.” Moralistic author Rev. Clark wanted the home folks to know that Crounse didn’t play cards, gamble, drink or worse as so many of the Civil War soldiers did.

Alas, in the humid, warm climate where malaria and dysentery was prevalent, Crounse became ill and grew weaker, eventually draining his strength. He was unable to campaign with his regiment when they left for Port Hudson and active duty. Instead, forced to remain behind at Camp Bonnet Carre, he entered the camp hospital.

Death came quietly and peacefully with Crounse relying “on the infinite mercy of his Redeemer and possessing a firm conviction of his acceptance.” He died June 28, 1863.

The next day, E.H. Merrihew, Captain of Co. B, wrote a letter of sympathy to Crounse’s brother, informing him of William’s death, which he claimed had cast a deep gloom over camp and that William would be missed. For some reason, Merrihew contacted William Crounse’s brother with this sad news, requesting that he tell “her” (Crounse’s wife?) of this tragic event instead of writing to her directly.

Burial was in the regimental cemetery at Bonnet Carre, Louisiana.

By mid-July, Albany newspapers carried notices of his death. The Albany Evening Journal reported on July 13 in its listing of Civil War deaths, “DIED” WM. CROUNSE, Orderly “Sergeant of Co. B, 177th Regiment, age 33 years at Camp Bonnet Carre, La. of fever, June 28th.” The Albany Argus carried a similar notice.

Controversial sermon

William Crounse’s death may have had no effect in the conflict between North and South, but it certainly resulted in major conflict in the town of Guilderland.

On Sunday, Oct. 25, 1863, the Reverend William P. Davis, long-time minister of the Helderberg Reformed Church at Osborn Corners, preached a lengthy sermon “occasioned by the death of William Crounse who died at Port Hudson in the service of his country.”

His words caused such a controversy that Reverend Davis commissioned Albany publisher J. Munsell to print his remarks in a pamphlet entitled “A Sermon Preached on the Fourth Sabbath of Oct., 25th,1863, occasioned by the DEATH OF WILLIAM CCROUNSE who Died at Port Hudson in The Service of His Country by Rev. William P. Davis, A.M., Pastor of the Ref. Prot. Dutch Church, Guilderland.”

A copy of Davis’s sermon pamphlet survives today in the files of the Guilderland Historical Society.

Modern Americans consider Lincoln one of our greatest presidents due to his political skill and patriotism as he led the war against Southern rebellion and issued the Emancipation Proclamation, forgetting that at the time not all Northerners supported the war aims of the administration.

While the Republican Party led by Lincoln gave its support to the conduct of the war, Democrats were split into two factions, the War Democrats who more or less supported the war effort and the Peace Democrats.

The Peace Democrats wished to negotiate a peaceful end to the war to restore the Union as it was. The Peace Democrats opposed the war, were outraged by the newly instituted military draft, and sought to elect a similar-minded Democrat as president in 1864.

They publicly proclaimed their feelings by wearing an emblem made from cutting the head of liberty from an old-style penny and pinning it in their lapel. They became known as “Copperheads,” both in reference to the penny and to the poisonous snake.

In the preface to his sermon, Reverend Davis claimed that he prepared his “discourse” at the request of William Crounse’s friends. What Davis claimed he was attempting to show was that Crounse died “in a noble cause; in defense of a divinely instituted government” and to “instruct” those “who were loud in their assertions of the unlawful acts and arbitrary power assumed by the administration, with threats of resistance.”

While not likely every Guilderland Democrat was a Copperhead, that Sunday there was at least one in attendance at William Crounse’s memorial service who did not take kindly to being lectured about Union politics in the guise of a sermon and eulogy. His infuriated reaction was chronicled by the late Town Historian Arthur Gregg.

Storming out of the church in the midst of Reverend Davis’s remarks, this man, prominent in the congregation, returned later that day. In an era when individual families paid rent for “their” church pews, this hot tempered church member entered the Helderberg Reformed Church carrying his tools with him, tearing out “his” pew to remove it from the building.

Later he bragged to friends, “It came out easy.”

Gregg quoted John D. Ogsbury, long ago editor of The Altamont Enterprise, who as a child attended that church the next Sunday, saying, “We all looked with consternation at the gaping hole made in the block of seats across from us.”

After later meetings of the church’s consistory, the man who was not named by Gregg, was found “guilty of public schism, of desecrating the house of God, and of contumacy, and that he be and hereby is suspended from communion of the church.”

Reverend Davis in the preface to his lengthy sermon admitted that some were deeply offended on hearing it. He mentioned “misrepresentations which are already afloat.”

For a time, this whole incident must have been the talk of Guilderland accompanied by the bitter feelings that can erupt from intense political opinions.

In the meantime, William Crounse’s grieving family had his body disinterred from the Bonnet Carre cemetery in December and brought home to be buried in Albany Cemetery. While others continued to fight political and military battles, William Crounse was at peace.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

The huge Ferris wheel at the Columbian Exposition, invented by Frank W. Ferris, was so appealing that the concept led to the creation of an attraction still popular today. This tiny Ferris wheel made its appearance at an early Altamont Fair not long after being introduced at the Columbian Exposition of 1893.

Unlike the current controversy that swirls around Columbus and the impact of his voyages, to Americans in 1892 Columbus represented the heroism of a great explorer whose discoveries were considered the first beginnings of our great country.

The nation went all out to celebrate the 400th anniversary of his voyages with events ranging from patriotic programs in schools, to parades, erection of Columbus statues, the issuance of special United States commemorative stamps and coinage, and President Benjamin Harrison’s declaration of Oct. 21 as a national holiday honoring what was considered Columbus’s discovery of America.

Guilderland joined in with other Americans participating in commemorative activities.

That March, a message appeared in New York State’s newspapers, including The Enterprise, directed at teachers alerting them to the “National Columbus Public School Celebration to be held on October 12, 1892.” New York State Superintendent of Public Instruction Andrew Draper concluded by hoping that “trustees, parents, pupils and all will join to make this one of the greatest celebrations of the age.”

The pressure was on for teachers to plan public displays of student programs to instruct and entertain parents and townspeople.

When Oct. 12 rolled around, Altamont’s school children came through, earning much praise from the spectators who attended their program. Urged by The Enterprise to attend “to encourage teachers and pupils by your presence,” residents were not disappointed by the performance as students sang national airs and gave recitations with many of them in costume as they acted out dialogues.

Over at the small Fullers one-room school, children also put on a well-received program described by the Fullers correspondent as a “literary entertainment.” There were pupils marching, singing, and wearing costumes and the program ended with a dialogue of three pupils representing Liberty, George Washington, and Uncle Sam.

At the conclusion of the program, a flag was unfurled. Observing all of this was a “host of visiting relatives and friends of the children,” all praising the pupils’ performances.

Even the tiny Settles Hill School entertained their neighbors and parents with various exercises, ending with the unfurling of a flag for their audience. Guilderland Center pupils also raised a new flag after previous fundraising.

While no other reports of school performances appeared in The Enterprise, it seems there were probably programs on Oct. 12 in the town’s other schools as well since marking the event seemed to be a mandate from above.

Albany celebrates

When the Oct. 21 legal holiday arrived, Albany marked it with an all-day celebration featuring a series of parades, beginning in the morning with a firemen’s parade, followed in the afternoon with a military and civic parade, and closing the holiday that evening in a torchlight illuminated bicycle parade, bicycles being a new fad in 1892.

In one of the day’s earlier parades, the Altamont Band performed, The Enterprise commenting the next week, “representing our village, in company of the crack bands of the City, we feel proud of them.”

For this occasion, the D&H ran a special early morning excursion train into Albany making stops all along the line, including at Altamont and Meadowdale, with a return trip that night leaving Albany at 11:15 p.m.

The Enterprise weighed in the next week, writing, “Our Village was well represented at the Columbus celebrations in Albany and all seemed pleased with the exercises.”

Columbian Exposition

The next year, Chicago was the destination of many adventurous Guilderland residents who, along with millions of other Americans, journeyed to see the wonders of the Columbian Exposition. The culmination of the 400th anniversary celebrations of Columbus’s discovery, it was the greatest world’s fair of its time.

This international exposition, displaying 65,000 exhibits in buildings covering 686 acres, ran from May 1, when it was opened by President Grover Cleveland, until Oct. 31, 1893.

It’s no wonder that Guilderland’s Barney Fredendall commented upon his return home from the fair, “It will take two years to see it all.”

Organizers of the fair realized that attracting large numbers of visitors was essential to its success. While “hype” may be a modern term, those 19th-Century businessmen seemed to grasp the concept.

A steady stream of press releases, accompanied by woodcut illustrations of buildings and attractions were sent out to 30,000 U.S. and Canadian newspapers to stir up excitement among their readers.

The Altamont Enterprise was apparently on the mailing list, running frequent, lengthy front-page articles with headlines such as “The Rush at Chicago,” “Getting Ready For the Opening of the Fair,” “The Fair is Ready,” “The Fair is Open,” “The Great Fair — Bewildering and Amazing Midway Pleasures,” and “The Great Fair — Its Fascinating Beauty Under Summer Skies.”

How to get from Guilderland to Chicago and at what expense were the prospective fairgoers’ first considerations. The writer of The Enterprise’s “Village and Town” column asked readers, “Are you going to the Fair? If so, you should see the inducements offered by the World’s Fair Excursion and Hotel Association. For particulars apply at the Enterprise Office.”

An alternative choice came from Ferguson and Wormer in Voorheesville whose Enterprise ad invited those wishing to view the fair to join the World’s Fair Association to “save money and secure comfortable hotel rooms.”

Both of the railroads serving Guilderland advertised in The Enterprise special rates to travel to the Midwest. For $16.50, the D&H offered a round-trip ticket for Chicago-bound passengers willing to take specially scheduled excursion trains. One left Altamont at noon, Monday, July 24.

After transferring to the Erie Railroad at Binghamton, the travelers arrived in Chicago at 4:15 p.m. the next day. Passengers must have reached their destination with the 1893 version of jet lag after riding sitting up on day coaches throughout the 28-hour trip.

More affluent fairgoers could travel on a regularly scheduled train, paying for a $26.50 ticket that included sleeper-car accommodations. The D&H assured ladies traveling alone that special preparations were made for their convenience and comfort.

Guilderland Center and Fullers Station’s depots were on the route of the West Shore. A West Shore ad during the last weeks of the fair offered special rates on “magnificent excursion trains,” the special round-trip ticket from New York City for $17, which was proportionately reduced from stops along the way.

Travelers would be accompanied by a West Shore agent who would advise regarding accommodations in Chicago and point out the sights along the way. Fares on both railroads dropped during the last weeks of the fair in the autumn.

Upon arrival in Chicago, a fortunate few were able to stay with relatives living in the area as did Fullers Station’s Mrs. Charles Decker and her daughter Cora. The Misses Anna and Lulu Lockwood of Altamont planned to visit with their brother Dr. John F. Lockwood, “his home being a few miles from Chicago.”

The Enterprise editor John D. Ogsbury recommended the “commodious quarters” provided by Mr. and Mrs. Edward Hart, former Guilderland residents, and stayed with them himself when he and his wife spent 10 days at the fair in July. However, most of the visitors stayed in various hotels.

A great number of those Guilderland residents who had the stamina and the money to attend the fair did so. By May 19, The Enterprise editor commented that “a number of residents in the vicinity have registered for the World’s Fair trip.”

During the summer, he noted, “The matter of a visit to the World’s Fair is becoming an epidemic.” Throughout the summer, the local columns in The Enterprise mentioned names of those who had departed for the exposition.

In October, the editor noted, “It has been computed that 45 persons from this incorporated village attended the world’s fair during the past few months. With those who live in the immediate vicinity, we have done remarkably well to swell the crowds at the exposition.”

An informal survey of other Enterprise columns during the fair’s operation shows mentions of McKownville sending five plus family members, three from Meadowdale, 25 from Guilderland Center, eight from Fullers, five from Guilderland, and four from Dunnsville. Surely there were others whose names weren’t in the paper or one name was listed when that person was accompanied by other family members.

After these fairgoers paid their 50-cent admission, what was there to do and see? Huge buildings lined a lagoon where visitors could be enlightened about the latest technology, and for many it must have been their first encounter with electricity.

Fair visitors could view exhibits from places as diverse as Turkey, New South Wales, or Ceylon and could observe natives from many areas.

Probably most fairgoers would have agreed that the Midway Plaisance was the best part of the fair. That new invention, the Ferris wheel was the hit of the exposition, standing 264 feet high with 3- foot cars, each holding 60 people, powered by huge engines.

Another popular attraction was a captive balloon ride that took brave souls 1,500 feet above the fairgrounds. There were restaurants with foreign foods, Algerian and Egyptian belly dancers, and an ostrich farm — the list of attractions was endless.

John D. Ogsbury’s lengthy letter from Chicago describing the fair marveled at the Ferris wheel although he chose not to try the ride. He mentioned the various buildings holding exhibits and was fascinated with the New York Central Railroad exhibit of Engine 999 that had recently broken the all-time speed record parked next to the DeWitt Clinton, the original train that first ran in New York State.

Many people remained at home, tied down with responsibilities, lacking the money, or were not well enough to travel that far and cover the extensive grounds of the fair.

They could view it all vicariously by attending events such as the “grand panoramic exhibition of the World’s Fair” at the Reformed Church when an entertainment under the auspices of Messrs. Felkins and Shafer of Albany would show a complete photographic panorama of “the marvelous buildings, exhibits, scenes and surroundings of the World’s Columbian Exhibition.”

Admission was 25 cents for adults and 15 cents for children under 12.

For those fortunate enough to have visited the exposition, it was the experience of a lifetime. Christian Hartman probably was typical of fairgoers, returning home “delighted” with his experiences, while Maggie Hurst said, “The fair is great and everyone ought to see it.”

The celebration had come to an end, and Columbus Day became a fixture in American life until recent years when controversy has arisen about Columbus and his holiday with a movement among some to replace it with Indigenous Peoples Day.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

The Sharp-Jeffers House stood opposite Judge Jacob J. Clute’s house on what was a working farm. Just beyond the two houses on Western Turnpike was a covered bridge over the Normanskill which was removed in the early 1920s when Route 20 was paved. This house is no longer standing.

Sitting impatiently, waiting for the light to change at the intersection of routes 158 and 20, few drivers are aware that these corners have a rich history dating back to the 18th Century. Once this area was part of a land grant called Elizabethfield, a wilderness tract of 1,322 acres running along the fertile banks of the Normanskill, a 1764 gift from Patroon Stephen Van Rensselaer II to his daughter, Elizabeth, and new son-in-law, Abraham Ten Broeck.

Gilbert Sharp, a Revolutionary War veteran who had served in Albany County’s 7th Regiment, was deeded a parcel of 161 acres plus 20 perches (an obscure English measurement) along the Normanskill in 1801. Our late town historian William Brinkman noted that Gilbert Sharp had “Land Bounty Rights,” but it is not clear if this was a factor in his acquisition of this part of the Elizabethfield grant.

About the same time that Gilbert Sharp took possession of his land, the Great Western Turnpike was laid out, cutting through the center of his farm. According to Brinkman, Sharp took advantage of turnpike traffic through what was a sparsely populated section of the turnpike to run some sort of tavern.

The site of his house, barn, and family cemetery were located on the southeast corner of what became a crossroads. Sharp family descendants farmed this land for over a century until their land was taken away from them by the city of Watervliet in about 1917. Watervliet used power of eminent domain to dam the Normanskill to create a reservoir, flooding several farms along that length of the waterway.

Arthur P. Sharp’s 1928 obituary stated he was the last descendant to have been born and lived on the old Sharp homestead until forced to move. The farmhouse and barn are now long gone and that corner is overgrown with trees and brush. The family cemetery still remains.

At an early time, a road, probably nothing more than a dirt track, connected the area of Hendrick Appel’s Tavern and the original Helderberg Reformed Church (now called Osborns Corners — the intersection of routes 158 and 146) ran north past Gilbert Sharp’s farm, crossing the Great Western Turnpike (now Route 20), to create the intersection.

By the early 1900s, this became known as Sharp’s Corners because supposedly there was a member of the Sharp family living on each corner. This road continued on to cross Old State Road at Parkers Corners and beyond to Rotterdam. Today this is designated Route 158.

Farms

County Judge Jacob J. Clute, a local celebrity who was esteemed as “a prominent and highly respected citizen,” owned a gentleman’s farm along the Normanskill, which was the family’s summer home. His name appears frequently in The Enterprise, both socially as a summer resident and professionally relating to cases in his court.

With his brother-in-law as farm manager, the property was in operation as a year-round farm where fine carriage horses were raised. The judge made many improvements to the house, which was a local showplace.

His niece Ina Clute inherited the property, marrying Lloyd Sharp; the couple lived there until the 1970s. The house and barns remain today. The Clute farm occupied the southwest corner until eventually a corner lot was sold off and has been the site for various commercial purposes since the 1920s or 1930s.

Across the Turnpike from Clute’s home was another imposing home acquired by Arthur Jeffers who married a member of the Sharp family. Sadly, after several changes in ownership, this lovely house burned in 2004.

When the Jeffers lived here, the property was part of a working farm. The original barn burned in 1927 and Mr. Jeffers invited his neighbors to help with a barn razing (that’s quoting the announcement in The Enterprise!) before erecting a big new barn that year, which still stands today.

Sometime in the 1920s or 1930s, the northwest corner of this property was sold for a service station as well. The whole area around the corners was originally agricultural, and many other families farmed in addition to the Sharps.

In the marshy overgrowth along the Normanskill and its tributary the Bozenkill or among stands of woods then still to be found in the vicinity, so much wild game abounded that it was a sportsman’s paradise. Hunters’ exploits were often reported in The Enterprise.

During the spring of 1888, three minks and 75 muskrats met their end, shot by Alvin Sharp who by December 1895 had already killed three foxes and 140 partridges and trapped 40 skunks. The pelts could be sold, supplementing a farmer’s income.

The stands of trees not only provided shelter for wild game and firewood for stoves, but extra cash for farmers as well. In 1893, Gilbert Sharp sold “lots” of trees, receiving “fair prices” for the timber.

A hemlock tree from Peter Sharp’s farm (now the Knaggs farm on Route 20) was taken to Tygert’s Saw Mill on Black Creek not far away, where it was expected that it would produce 1,200 feet of lumber. Having that saw mill a mile away provided a ready market for timber.

Although Sharps Corners had its own identity, it was simply an area of working farms on a crossroads. Unlike other area hamlets, there was no one-room school, church, general store, or post office.

Children hiked a distance either to Osborne Corners or Dunnsville schools. Churchgoers trekked to either Parkers Corners Methodist Church or Helderberg Reformed Church at Osborn Corners. Until the advent of Rural Free Delivery in the 1890s, residents had to travel to Dunnsville for their mail and there or to Fullers to shop at a general store.

Transformed

The 20th-Century arrival of the automobile and the designation of the Western Turnpike as U.S. Route 20, a main route into western New York, transformed Sharps Corners especially after Route 20 was paved through that section in the early 1920s.

There was money to be made from all those travelers passing through and, by 1927, Al and Eleanor Folke opened a Texaco gas station, restaurant, and tourist cabins on the northeast corner of the intersection.

A menu surviving from their Sharp’s Corner’s Grill offering “real home cooking” and the additional information, “yes, we have beer” dates the menu from the time when Prohibition ended or soon after.

An official notice in The Enterprise on July 14, 1933, announcing that beer and wine could be consumed “on said premises,” shows the Folkes wasted no time getting permission to sell alcohol at their restaurant.

Breakfast, lunch and dinner were offered at 1930s prices — pork chop dinner 60 cents or steak and potatoes, vegetable, bread and butter, coffee, tea or milk for 75 cents. Their place sold ice cream and candy as well, attracting neighborhood children on their way home from school.

After Al Folke’s death in 1959, his wife, Eleanor, continued the business with help from Walter A. Sharp, her neighbor, until 1968. The restaurant was eventually converted into a residence and within recent years was demolished along with the remaining derelict cabins. Wooden sheds are sold on the property today.

This intersection saw not only increased through traffic on U.S. Route 20 but, as more and more Guilderland residents took jobs at General Electric, Route 158 traffic volume grew as well, making these corners the perfect location for a gas station or two as time went by.

On the northwest corner, two brothers-in-law, Evan Crounse and George Armstrong, opened the Sharp’s Corner Garage in 1930, “always at your service,” doing general repairs and Chevrolet Sales and Service in addition to selling gas.

There were eventually two garages facing each other across Route 20, each with a series of owners. Another longtime garage there was Sands Esso Service Center and today is the site of Ma’s Gas Station.

With the volume of traffic flowing in all directions, often at high speed, Sharp’s Corners quickly turned into a deadly intersection. Endless accidents, often leading to fatalities, occurred there especially after Route 20 was paved in the early 1920s.

After one more tragic death in 1930, Supervisor Edwin J. Plank went to Albany to appeal to the State Highway Department to place a stoplight at Sharp’s Corners. Claiming in recent years there had been five persons killed at this intersection, not to mention the numbers injured and the damages to automobiles, he was apparently successful in his quest for a traffic light.

When, in 1935, another man died in an accident at the intersection, it was noted, “The light was not working properly and may have been the cause of the crash.”

It must have been one of the first, if not the first, traffic light in the town of Guilderland, although it may have been a flashing red-yellow light instead of the type that is there now.

Folke’s tourist cabins had become outdated after World War II when more sophisticated travelers demanded additional amenities. William and Trudi Goedde opened the Charldine Motel two-tenths of a mile east of the intersection, looking across Route 20 to the reservoir and escarpment beyond.

Once the Thruway opened its full length in the mid1950s, traffic on Route 20 became mostly local causing motel owners to scramble to find new sources of income.

In 1961, the Goeddes were offering to rent motel rooms on a long-term basis to new teachers while three years later they advertised the Charldine Rest Home connected to the motel, catering to the elderly by the week or all year-round.

By 1966, they opened a restaurant with spaghetti dinner and southern fried chicken on the menu. Finally, in June 1971, the Goeddes sold their Charldine Motel to Mr. and Mrs. Ditterly.

One February night in 1979, fanned by high winds, a destructive fire raced through the motel destroying it. The property where it was once located stood vacant and overgrown until 2010 when commercial buildings were erected there.