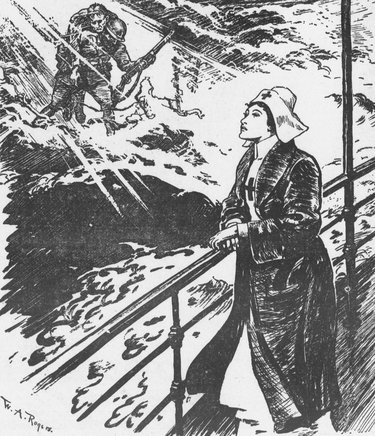

— Library of Congress

“The Call From No Man’s Land” was the caption on this May 10, 1918 newspaper picture accompanying a story on fundraising for the Red Cross, saying, “Every dollar spent alleviates misery.” It was printed in the Cottonwood Chronicle in Cottonwood, Idaho, similar to newspaper pleas that ran across the country.

The United States’ declaration of war on April 6, 1917 forced the American people to respond to the crisis of World War I. Guilderland residents met the challenge, giving overwhelming support to the nation’s war effort and to the troops shipped overseas.

Within days of the declaration of war, 200 people gathered in Altamont’s village park for a patriotic rally where the pastor of St. John’s Lutheran Church addressed the crowd, accompanied by selections played by the Altamont Band. American flags began to be flown on homes and businesses.

The reality of war was evident in Altamont when two weeks later a train of eight Pullman cars carrying 400 Marines, “a husky looking bunch,” passed through bound from Chicago to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Red Cross

President Woodrow Wilson, as honorary president of the Red Cross, appealed to citizens’ patriotism to help the Red Cross through monetary donations and volunteer activities in assisting the organization’s support of soldiers on the battlefield.

Additionally support was needed for its broader mission of sending supplies to prisoners of war and helping civilians, especially children, in the devastated areas of Europe. Wilson issued a summons during the week of Dec. 16 to 23, 1917 for everyone to enroll in the Red Cross, promising that every cent raised would go to war work.

Membership cost a dollar. Schoolchildren were reached through the Junior Red Cross. Several hundred people from Guilderland donated their dollars during the 18 months the United States was at war.

A variety of events were held around town specifically to benefit the Red Cross. In Guilderland Hamlet, “Keep the Home Fires Burning,” a patriotic cantata was presented at the Hamilton Presbyterian Church while in McKownville an entertainment was scheduled at the Methodist Church, admission 25 cents.

A movie night at Altamont’s Masonic Temple featured three reels, which not only depicted scenes of General John J. Pershing and the American Army, but also showed the vital work of the Red Cross “over there.” The show included patriotic songs as well, all for 20 cents.

A dancing party given at the town hall in Guilderland Center raised $100 from the 200 people who attended. These are just samples of fundraisers held at that time.

Volunteers in McKownville, Guilderland Hamlet, Guilderland Center, and Altamont pitched right in, quickly establishing Red Cross chapters in their communities with women in the nearby hamlets of Dunnville, Fullers, and Meadowdale working as part of these chapters.

The Red Cross meetings followed a regular schedule, either in private homes or in public places such as the town hall in Guilderland Center, Temperance Hall in Guilderland Hamlet, or Masonic Hall in Altamont, often lasting all day.

These women made huge amounts of materials to be sent periodically overseas to the Red Cross and lists of the many supplies that were shipped appeared in The Enterprise. Quantities included 333 compresses, 348 head strips, 25 sweaters, 18 pairs of wristlets, 244 handkerchiefs, 92 arm slings, 7 ambulance pillows and 10 hospital shirts.

These numbers represent amounts included in a single shipment. Pajamas seemed to be another big item. The production of these small groups of Guilderland women was tremendous, representing a huge contribution to the war effort if multiplied by women all over the country.

Tobacco Fund

Appealing to the generosity of its readers, The Enterprise opened a campaign in early October 1917 to send tobacco to soldiers overseas.

For a 25-cent donation, each serviceman would receive two packages of Lucky Strike cigarettes, three packages of “Bull” Durham tobacco, three books of “Bull” Durham cigarette papers, one tin of Tuxedo tobacco, and four books of Tuxedo cigarette papers, a value of 45 cents.

And in addition a postcard was included, which could be sent back to the donor thanking him or her. Week after week, the appeal was featured in the center of the front page illustrated by a large drawing illustrating soldiers gratefully receiving their smokes, often showing the Red Cross handing over the package, or soldiers puffing their cigarettes to keep them calm with shells exploding around them.

Names of donors and the amounts sent in were listed weekly for everyone in the community to see.

Although the editor admitted he had received some letters condemning the Tobacco Fund as immoral, it was felt the men really needed their smokes on the battlefield.

One headline read, “Physicians Endorse the Tobacco Fund for the Soldiers,” while an anonymous officer was quoted, “My men will bear any dirt or discomfort as long as they are supplied with smokes.”

One week’s appeal stated the men were just as dependent on cigarettes as they were on food. “The loud uproar of battle, the discharge of the heavy guns, the bursting of enormous shells and the charge of the yelling battalions are enough to send the average man to the ‘insane ward,’” with the implication that their smokes would help them through this ordeal.

The whole idea originated with the American Tobacco Company in what was really a clever and lucrative marketing scheme, getting the newspapers to collect the money and the Red Cross to deliver the cigarettes to the front lines.

The name of the company involved only came out when they were forced to send out a letter a few months later to be published in all these newspapers apologizing, offering an explanation as to why none of the donors were receiving their thank-you cards.

They claimed the tobacco had been shipped to France, but the rail lines to the front were so congested that the tobacco was piling up in port. Eventually a response was received by a Meadowdale man that said, “I received your tobacco today and was more than thankful for it.”

The campaign came to an end May 1, 1918 when the American Tobacco Company notified newspapers they were discontinuing the Tobacco Fund since the U.S. government was taking their entire output of Tuxedo and “Bull” Durham tobacco.

During the course of the campaign, The Enterprise had received $133.50 donated to the Tobacco Fund and in addition, had received much advertising for Lucky Strike cigarettes and “Bull” Durham tobacco.

Anti-German sentiment

Anti-German emotions ran high in part because the United States government created the Committee for Public Information to spread anti-German propaganda.

The Enterprise ran a series of 15 articles obviously coming from an outside source with such titles as “Diaries of German Soldiers Tell of Murder and Pillage in Belgian Cities” and “Germany Guilty of Barbarities in War Conduct.”

In a cartoon supporting a bond drive, a hapless dachshund wearing a German officer’s helmet represented the enemy.

Altamont High School was one of many American high schools that removed German language from its curriculum.

Ads appeared in The Enterprise for some time paid for by the American Defense Society, headlined “To Win This War German Spies Must Be Jailed.” Listing a New York City address and endorsed by an advisory board including former President Teddy Roosevelt, the group requested a donation for membership and urged readers to ”telegraph, write or bring us reports of German activities in your district.”

Germans were frequently referred to as Huns or Boche in print or picture.

Cutbacks in food and fuel

Changes intruded on everyday life. For the first time ever, daylight saving time was instituted to save fuel.

In early 1918, fuel-less Mondays were attempted. The D & H ran its limited Sunday schedule again on Monday as well, which meant Altamont High School remained closed on Monday and rescheduled classes for Saturday because so many of their students commuted by train and couldn’t get there on the revised Monday schedule.

Local businesses closed down, although grocery stores were exempt.

January 1918 was the coldest since the Albany weather bureau was founded and the ice on Black Creek near Osborn’s Corners where the Tygerts cut ice blocks was reported at 38 inches thick. Local temperatures were reported as low as -26 degrees.

However, at Masonic Hall, a special “Fuel-less Holiday” five-reel movie program was showing for only 10 cents. Fuel-less Mondays were impractical and were soon discontinued.

Another inconvenience was learning to do with less wheat, because huge amounts were diverted to Europe to feed troops and starving civilians. Recipes appeared in The Enterprise for substitutes like biscuits made with parched corn meal and peanut butter or for potato cutlets!

For a time “Hooverize” became a new word in American’s vocabulary. A major aspect of Hooverizing was meatless Mondays and wheatless Wednesdays. One slogan was, “When in doubt, eat potatoes.” An Altamont bakery offered some wheatless alternatives.

St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Guilderland Center even ran a Hoover dinner, named after Herbert Hoover, appointed head of the U.S. Food Administration.

War bonds

Citizens were asked to share the country’s financial burden of the war by buying bonds. In the 18 months that we were involved in the war, the government sponsored four Liberty Loan bond drives, assigning a quota to be reached by each community.

Committees were set up, and usually a patriotic meeting or rally kicked off the drive to psych the people to subscribe for bonds. Bond purchasers’ names were published in The Enterprise as well as the dollar amount pledged.

Quotas always seemed to be exceeded, at least in part because it would have been an embarrassment to you and your family to have your name missing from the list. In the Fourth Liberty Loan drive, the quota for Altamont and vicinity was $40,000 and this after three previous quotas had been met and exceeded.

During the Fourth Liberty Loan drive a special “Yankee Trophies” train of eight Pullman cars and some flat cars stopped in Altamont on its way along the D & H line. Captured German field guns and other large articles of war were displayed on the flat cars while inside the Pullman cars observers could walk through, inspecting German helmets, machine guns, gas masks, and hand grenades.

After their opportunity to view the battle souvenirs, people were to attend a huge rally when they could make pledges to buy bonds. The quota was passed in spite of the Spanish influenza epidemic spreading through town at the same time.

Simultaneously large ads were running in the paper promoting the fourth bond drive each with the name of many local businesses such as Altamont Bakery, Becker’s Livery, and CJ Hurst down at the bottom as sponsor. Publicity and peer pressure surely played a part in getting people to support these bond drives.

Draft

Much newspaper space was given over to news of the draft after the Selective Service Act was passed on May 17, 1917. Lists of eligible men and locations where they were to report were prominent local news.

The newsy columns from Altamont and the other hamlets of the town often contained names of men who either had left for training camps, left for overseas, or were home on leave.

Whenever correspondence penned by a local serviceman was shared with The Enterprise, it was printed, giving the local population a personal glimpse of the front lines “somewhere in France.”

J.H. Gardner Jr. of Meadowdale actually sent home a war souvenir German helmet, put on display for a few days in the Enterprise office.

Guilderland Center’s Dr. Frank H. Hurst, one of the first to arrive overseas, was initially assigned to a British field hospital and later was in command of an American field hospital. Wounded twice and then gassed, he was a prolific letter writer and several of his lengthy descriptive letters, one of which was written on captured German paper, were shared with newspaper readers.

Fortunately, on Nov. 11, 1918, eighteen months after the United States entered the war, it was over.

Life in Guilderland quickly returned to normal, but for the young men who actually were part of the trench warfare “somewhere in France” things would never be quite the same.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Fort Hunter School as it was is shown with the 1935 two-room school and the 1953 eleven-classroom building attached. Within a year of opening, it was overcrowded. However, with a later decline in enrollment, this building was closed in 1972 and demolished in 1999. Today a senior apartment complex stands on the Carman Road site.

V-E Day, V-J Day, the war was over, the boys were returning home! And the babies started coming, and coming — the Baby Boom had begun.

Guilderland was one of New York’s many rural communities that quickly experienced rapid housing development and population growth in the post-war years. Yet townspeople were still relying on an antiquated education system of one- and two-room common schools with Altamont the only Union Free District offering an old, overcrowded high school.

The late 1940s found Guilderland’s schools jammed with children also attending classes in church or school basements, in one case in a private home or being bused out of town to Draper and Bigsbee schools in Rotterdam, or Schenectady, or Albany and Voorheesville schools.

The time had come for a serious discussion about uniting the 10 school districts of Altamont, Dunnsville, Fort Hunter, Fullers, Guilderland, Guilderland Center, McKownville, North Bethlehem, Osborn Corners, and Parkers Corners.

A steering committee, having been organized, aimed to put centralization to a vote by July 1950. In advance, a series of informational public meetings emphasized the need for better schools as well as a discussion of the costs.

The proposal presented at these public meetings included a junior-senior high school with three elementary schools — at Fort Hunter, Altamont, and McKownville — to cost $2,600,000 to be raised by a bond issue. A petition had been sent to the state’s education commissioner to set a date to vote on the proposal to centralize the 10 districts into Guilderland Central School District, No.2.

Scheduled for June 20, 1950, from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., a public meeting to vote on the proposal to centralize was to take place at the Brownell Bros. Albany-Schenectady Bus Line Inc. garage in Guilderland Village. If the measure passed, a school board was to be elected at the meeting.

When the votes were counted, out of the 2,007 cast, 1,302 were in favor with 703 opposed and 2 void votes. A board of education was then elected with 1-, 2-, and 3-year terms to be led by William D. Borden.

The original 10 districts turned over any surplus funds to the new central district. Ralph Westervelt, principal of Altamont High School, was named supervising principal of the new district at a salary of $5,500.

Teachers would be kept on, but would begin in September 1950 to earn years toward tenure, although any teacher with five or more years in one of the 10 districts would be given one year toward tenure. A second vote in September agreed to the purchase of five new school buses for a total of $31,000.

Planning

In the meantime, 56 volunteers formed the Citizen Planning Committee, dividing into five subcommittees, which worked on the areas relating to population growth, facilities, program, finance, and public relations.

They suggested three new elementary schools to serve kindergarten through sixth grade. The committee found the current Altamont school building “wasn’t adaptable.” In McKownville and in Fort Hunter, the two-room schools built in 1935 were to be used.

Students in grades 7 to 12 would attend a new junior-senior high school, site to be determined.

The committee did not recommend one K-12 school, but rather favored community elementary schools for a variety of reasons. “The District is in a strategic area, when all of our children might be exposed to a single bomb attack if housed in one school,” the committee said.

This thinking may seem ludicrous today, but was made when the trauma of World War II still lingered, the Korean War was raging, and Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union had recently developed the atomic bomb, while in the midst of Guilderland was a very active Army depot.

These reports were sent to households followed by four informational meetings in different parts of town. Citizens’ main questions revolved around taxation issues and building sites, 18 of which had been reviewed by one of the subcommittees. Considerations were drainage, adequate water supply, preparation of the site for building, and access to public transportation.

Opposition

Remember those 703 voters opposed to centralizing the ten districts? They hadn’t gone anywhere.

A group of them, chiefly Westmere residents under the leadership of two men, George E. Craft and Edward T. Zeronda, had hired attorney Thomas J. Mahoney to represent them in dealings with the board of education.

The district’s annual meeting, held at the bus garage, showed the undercurrent of opposition from the Westmere group whose leaders kept claiming to favor centralization, but opposed higher taxes.

A $60,000 surplus the board had hoped to save as a “cushion” to keep taxes lower once building began was voted down by a big margin, the attitude being, “Why should present residents who may move away pay for something to be used by others, some of them newcomers?”

The sites to be voted on, on July 24, included a very few acres to add to the school property at the existing Fort Hunter School.

The McKownville K-6 choice was either the Van Loan parcel on Route 20 opposite the intersection with Fuller Road or the Loeper site on Johnston Road in Westmere.

The junior-senior high school choice was between the Matulewicz site in Guilderland Center or the Crapser-Mattice-Heckroth site at McCormacks Corners. This site at McCormacks Corners would have to be legally condemned because the owner of the largest parcel was reluctant to sell.

Shortly before the site vote, a large paid notice appeared in the July 13 Enterprise placed by Marvin Armstrong, a disgruntled man who was anxious to sell his parcel west of the Crapser site further out Route 20.

He led off with the real-estate plans the Crapser-Mattice interests had in place for land that would be condemned, stating, “The owners plan to fight to the last ditch. Maybe they will lose, but it will be costly to the district.”

Of his own acreage on offer, Armstrong asked, “Wouldn’t it be better than gamble on a comparable site at possibly FOUR OR FIVE TIMES THE COST?”

A response from the board’s counsel, Borden H. Mills, noted that Armstrong’s site had ravines needing extensive grading, lacked a reliable water supply, and was not on a public-service route plus the further distance meant longer times on school buses coming from the outer areas of the district.

Voters on July 24 chose the Matulewicz site in Guilderland Center for the junior-senior high and the Loeber site on Johnston Road for the McKownville K-6 school, approving the purchase the few acres at Fort Hunter plus a bond issue for the purchases.

Out of 1,550 votes cast, there were 270 void on the elementary school vote and 243 void votes on the junior-senior high sites.

The Westmere group’s leaders immediately challenged the outcome, claiming site ballots were “ambiguous and confusing” and “did not give a fair chance to vote in the negative.” The appeal to overturn the election was sent to the state’s education commissioner.

The Westmere men claimed their citizens group had “widespread support in the community” with the citizens group opposed to “the high costs.” The discontented taxpayers claimed there should be a “compromise,” admitting the present education was “wholly inadequate,” but that centralized proposals were “financially unrealistic.”

Board Counsel Borden H. Mills contradicted the contention that the ballots were “flawed” with the wording published in three different newspapers previous to the voting.

Then he commented on a mimeographed sheet labeled “School Taxes” left at his home shortly before the site vote which urged in large type: “VOTE NO – ALL THE WAY.”

Revote

After a Sept. 10 hearing, Education Commissioner James Edward Allen Jr., who later served as President Richard Nixon’s Commissioner of Education, set aside the votes for both the McKownville elementary and the junior-senior high sites, the basis for his decision being, “voters desiring one site did not have the chance to vote against the other.”

He ruled he must see the sealed votes to determine if the Fort Hunter and bond issue votes stood. Later he upheld these two results.

In October, the Guilderland School Board set Nov. 14 for the second vote to choose sites.

In the meantime, the Citizens Planning Committee extended an invitation to the Westmere men whose appeal to the commissioner had thrown out the original vote to discuss the question at a public town meeting where they were arranging a moderator.

The group’s spokesman refused any discussion at this time being as “unwise and not conducive to an understanding.”

The attorney for the Westmere group, whether expressing his own ideas or giving voice to the group’s members, suggested putting all the elementary students in the Fort Hunter school and cutting the cost of the junior-senior high school. Quickly rejected because too many small children would have very long bus rides, it was never considered.

On Nov. 14, not only was the choice simpler, but an actual sample ballot was published, unlike the previous vote on sites when the ballots were more complicated.

Days before the vote, the school board recommended a “yes” vote, reassuring voters that, even though the Matulewicz site was adjacent to the Army depot, they should have no fear of it being bombed.

This time, it was either “yes” or “no” on purchasing the 19-acre Loeber site for the elementary school and the 62-acre Matulewicz site for both the junior-senior high school and a bus garage. When all the votes were tallied, 965 voted in favor while 388 were opposed and 13 ballots were void.

New schools open

Plans for the new school buildings were released in January 1952 with a bond issue vote planned to fund their construction. School floor plans and exterior images of finished buildings plus a 12-bus garage were published.

The bond issue totaled $3,204,900.

This time, voting at Guilderland’s Willow Street School on March 1, there were 1,406 votes cast with 1,232 voting yes with only 164 voting no and 10 void ballots.

By September 1953, the Fort Hunter, Altamont, and McKownville-Westmere elementary schools opened. Although there was still completion work to be done, it did not interfere with the educational program.

The days of the one-room schools had ended.

For one more year, secondary students would be sent out to Draper, Albany, Voorheesville, or Schenectady. Finally, in September 1954, Guilderland Junior-Senior High School opened when 650 seventh- through 12th-graders arrived at a school with the most up-to-date facilities.

With the explosive student growth over the next years, these schools were soon overcrowded and the bond issue and building process had to begin anew.

It had been “an uphill effort” to centralize and provide modern education facilities and programs for Guilderland’s rapidly growing school population.

From the vote to centralize to finally opening four new schools, it was thanks to the efforts of volunteers from school board members, committee members, and all those people who helped with the various votes that had taken place to accomplish this.

Board members of that day — who dealt with questions of whether or not to include agriculture as a high school program or dealt with fear of bombing raids — could hardly imagine the issues facing today’s board of education.

However, there has been one constant from 1950 to the present day: disgruntled taxpayers.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

The Hartman family lived in this house beginning in the late 1840s. Hartman family members ran a blacksmith shop on the opposite side of the Western Turnpike. The intersection, now the site of Stewart’s at the corner of routes 20 and 146, is still called Hartmans Corners today.

What a stretch of the imagination it takes for contemporary Guilderland residents, all 37,848 of us in 2020 and still increasing, to visualize the same 58.7 square miles populated by only 2,790 people in 1840.

A small number lived clustered in the tiny hamlets of Knowersville, then located east of modern day Gun Club Road; Guilderland Centre, as it was spelled in those days; Dunnsville; and Guilderland — each with its own post office and one-room school.

Smaller numbers lived in neighborhoods near Fullers Tavern and McKown Tavern, each also with its own school. The remainder lived scattered on farms spread throughout the town with isolated schools such as Settles Hill.

The main transportation routes were the Great Western Turnpike, now Route 20, which had been improved by planking one side for eight miles by the end of the decade. Connected to this turnpike was the Schoharie Plank Road, now Route 146, which led to Schoharie. Both required tolls for usage. The town’s other roads were dirt tracks, sometimes impassible depending on weather.

Churches serving the town in the 1840s included Hamilton Union Presbyterian Church in a relatively new church built in 1834, St. James Lutheran and Helderberg Reformed, each located between Knowersville and Guilderland Centre.

In addition, short-lived Baptist and Catholic congregations used a building in Guilderland later known as Red Men’s Wigwam. Methodism was attracting many townspeople who were meeting at private homes, at Spawn’s Mill, and on at least one occasion holding a camp meeting on the Chesbro farm. Their first church in Guilderland wouldn’t be built until 1852.

Amazingly, due to the New York State Census taken in 1845, we now know a tremendous amount of detailed information about those who were living here at that time. The state’s 1821 Constitution required a state census be taken five years after a federal census and this continued to be a practice until 1925.

Residents

In 1845, the total population of 2,995 had grown slightly in the past five years, but this statistic was the tip of the census’s statistical iceberg. Broken down by sex, the numbers were practically evenly divided, the 1,501 males outnumbering the females by only seven.

The previous year had seen 51 male babies born while 22 males of all ages died. Forty-two females came into the world, but only 17 left it.

Over the past 12 months, 35 couples married, but there remained 259 single women between the ages of 16 and 45. Of the men, 206 were subject to serving in the militia while the number of persons eligible to vote — all male — was 682.

Also enumerated out of 2,995 were 47 persons of color with an additional three specifically noted as persons of color taxed. Assuming these three were males, they were eligible to vote. New York law allowed almost any white male to vote, but discriminated against African Americans, limiting voting only to those black men who paid taxes.

Citizenship, ethnicity, and place of birth were also surveyed. Out of 2,995 total, New York was the birthplace of 2,559, while 46 were born in New England and seven in other parts of the country.

Among the foreign born were 80 who had immigrated from Great Britain or its possessions, nine from Germany, one from France, and six from other parts of Europe. And one lone person originated from Mexico/South America. Of the 97 foreign born Guilderland residents 50 were designated as un-naturalized aliens. For whatever reason, this doesn’t quite add up to 2,995 total.

Another aspect of the population count distinguished those with special needs with designations that will make the modern reader cringe. In Guilderland, there were neither “lunatics” nor anyone “deaf and dumb.” However, among the townspeople there were three “idiots,” two males and one female, as well as an 8-year-old blind girl whose parents were listed as unable to support her. The town’s Overseer of the Poor would have had to deal with the needs of the four paupers in town.

Children weren’t forgotten. When, in 1812, New York state required townships to establish common schools offering a basic education up to eighth grade, Guilderland had divided itself into common school districts. In 1845, each district had a one-room school, all 10 having a total value of $1,650. Although there were 827 children between the ages of 5 and 16, only 628 were on teachers’ lists and not all of those attended school regularly.

Religion

Religious denominations were surveyed and the value of their real estate listed.

For some reason, the Lutheran Church was left out of the survey and perhaps that is why the number of Dutch Reformed Churches in Guilderland was listed as two, when at that time the Helderberg Reformed Churches were valued at $6,600, when there was only one Reformed Church at Osborn Corners.

Up the road at the modern-day entrance to Fairview Cemetery was St. James Lutheran Church and that may have been lumped in to make two Reformed Churches.

Additionally, there was one Presbyterian Church valued at $900, which would have been Hamilton Union Presbyterian Church in Guilderland, and one Baptist Church valued at $1,200, but this congregation was short-lived.

While there were many Methodist adherents in town, they were still meeting in private homes, at Spawn’s Mill, or on at least one occasion holding a camp meeting on a local farm. Guilderland’s first Methodist Church would be erected on Willow Street in 1852.

Economy

Economic activities took up a very large part of the overall census.

Listed as farmers or agriculturalists were 325 persons. Great attention was paid to the quantities of various crops raised, dairy products produced, and numbers of livestock on town farms.

For each crop, the statistics are extremely specific. Corn was planted on 448 ¾ acres producing 33,014 ¼ bushels while the buckwheat harvest was 35,654 bushels grown on 654 ½ acres. One wonders how they came up with these and other production figures that were so specific.

Other crops raised in various quantities included barley, peas, beans, rye, potatoes, wheat, and oats. The individual crops were listed with the amount of acreage planted for each crop and the quantity harvested.

The town’s proximity to the city of Albany must have been an advantage, providing a ready market for much farm produce above what families needed to survive. However, in addition to feeding themselves, farm families also bartered with town merchants for goods that couldn’t be produced on the farm or for services such as having a horse shod.

Their livestock also had to be fed in winter and poultry and hogs at least partially fed all year round from their farm’s produce. What was left after that was their surplus to sell.

In spite of factory manufactured textiles becoming increasingly available at this time, 84 acres were planted in flax with 7,266 pounds produced. Women of the town, using both flax for linen and wool, spun or wove 5,005 ½ yards of cloth in the previous year.

Much livestock was pastured, penned, or put to work on local farms. Counted were 2,567 “neat cattle,” a term meaning bovine, which must have included oxen, bulls, and calves.

It was noted specifically that there were 1,216 cows milked, the milk churned into 89,358 pounds of butter or pressed into 2,813 pounds of cheese. Providing meat were 3,277 hogs.

Power for farm work or travel depended on the 940 horses in town, although oxen continued to be used on the farm. At that time, there were 5,781 sheep that provided a huge amount of wool and fleeces.

In addition to the statistics as to amounts and production, dollar amounts were also listed for each item of production.

Water power provided by Guilderland’s waterways was used for two grist mills, which ground the grain produced on the farms — one at Frenchs Hollow and the other one Batterman’s Mill on the Hungerkill. Together, the processed flour was estimated to be worth $11,134.

Seven sawmills cut the lumber to build or add to existing houses, erect barns, or build bridges. Two tanneries tanned hides into leather worth $2,100.

There was a textile factory at French’s Hollow and perhaps that was where the carding machine and fulling mills were located, providing a market for all or a portion of the wool produced by the town’s sheep.

In 1845, sixteen taverns lined the Great Western Turnpike and the Schoharie Turnpike. There were four grocers and seven merchants, though it was possible that one person may have been involved in more than one activity.

Ten claimed to be manufacturers and 73 to be mechanics. At that time, this category would have included blacksmiths, wheelwrights, or tinsmiths. The statistics concluded with three clergymen and seven physicians such as Dr. Frederick Crounse who practiced in Knowersville.

Anti-rent agitation

One statistic that would have been of interest today was not included in what was quite a comprehensive overview of Guilderland in the 1840s would have been which acreage was freehold ownership and which was under lease to the Van Rensselaer interests, forcing the tenants to pay annual rents.

After the last patroon, Stephen Van Rensselaer, died in 1839, his heirs were determined to collect back rents. By 1845, anti-rent agitation had grown so intense that an Anti-Rent Convention convened in Berne with Knowersville’s Dr. Frederick Crounse chosen as chairman.

Guilderland residents witnessed Albany County Sheriff Christopher Batterman, a Guilderland resident himself, lead a group of New York State Militia through town on their way to the Hilltowns to put down anti-rent agitation, which men disguised as “Indians” had resorted to there.

Anti-rent pressure led to a revised New York State Constitution that changed tenure laws, but rent paying under the old, original leases continued for many years for some Guilderland farmers.

The 1845 census is the only New York state census with such extreme detail. It is fortunate to have such a detailed survey of our town from almost 180 years ago when there were few other written records to give a picture of what town life was like then.

— Photo from Guilderland Historical Society

One year, McKownville Methodist Church’s Sunday school party opened with a pageant presented by the children, followed by a visit from Santa, a Christmas tree, gifts, candy, and ice cream. All that and the Children’s Fairy was to visit as well. Everyone was cordially invited to remain after the program for the social hour. Another year, there was simply a Christmas party at the church when there was an invitation for “all children of the community.” There was much activity in all of the town’s churches during the Christmas season.

Black Friday deals early in November, blow-up Santas on lawns within days of Halloween, and some store decorations on display as early as September — Christmas or the “holiday” season seems to begin earlier each year. A look back at Christmas a century ago tells a different story.

In issues of The Enterprise from 1921 to 1923, the only mention of Christmas before Thanksgiving was advance publicity for sales of Christmas seals which were to be used in addition to postage stamps on Christmas cards or on wrappings of Christmas packages.

An idea adopted from Denmark in l907, the funds raised from their sales across the nation were used for the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis, a dread disease that killed 100,000 Americans annually in that era. Money raised in Albany County was used within the county for visiting nurses and a sanatorium in the Pine Hills section of Albany.

Commerce

Gift giving had long been a Christmas custom, but by the 1920s commercialization had begun creeping in with retailers promoting a wide variety of choices.

Christmas advertising was a bonanza for newspapers in that era with The Enterprise running ads from smaller Albany and Schenectady specialty shops and Schenectady department stores. Ads from Albany department stores were missing, perhaps because they felt people here would have already seen their offerings listed in the Albany papers.

Now that there was bus service from Guilderland to Schenectady plus private automobiles, Schenectady stores seemed to be making a serious effort to attract Guilderland area customers.

During these years, usually The Enterprise issue of the second week in December featured a page-one decorative Christmas illustration with a lengthy story publicizing all their advertisers, urging readers to patronize them. Throughout the paper, regular community news columns were interspersed with numerous ads, Christmas-themed illustrations, stories, and the occasional poem.

Schenectady’s big three department stores — Wallace Co., Carl Co. and H.S. Barney, “where everybody shops” — usually ran half-page ads familiarizing potential customers with the wide variety of gifts available. Additionally, they offered amenities such as restrooms and restaurants.

Carl Co. would reimburse carfare if you spent $20 or more in their store (a 1921-23 dollar equals $17 to $18 today), while Wallace’s would deliver your purchases for free. All of them stayed open a few specific nights before Christmas for shoppers’ convenience.

For the more budget-minded, Lurie’s, “The Store of Today and Tomorrow,” was the “Big Economy Store” in Schenectady.

Department-store basements were stocked with toys popular in that day with action toys for boys like trucks, Daisy air rifles, velocipedes (tricycles), circus vans, Lionel train sets, Noah’s arks, and bowling alleys among the choices. Girls were pointed in the direction of domesticity with toy ranges, carpet sweepers, laundry sets, doll furniture, dolls and doll carriages as their selections.

Even though the first store Santa appeared in New England in 1890, only Wallace’s advertised a Santa in its toy department “to greet children and listen to their wishes.” And for children too old for toys, City Savings Bank of Albany suggested opening a savings account in their name with a first deposit.

Price ranges for toys were sometimes printed, ranging from under a dollar for a few things such as Camp Fire Girls books for 25 cents each to Lionel train sets as high as $25.

Smaller Albany and Schenectady specialty shops offered clothing, leather goods, rubber products, fountain pens, Victrolas, umbrellas, and luggage — just a few of the items advertised. John B. Hauf of Albany suggested making it “a furniture Christmas” while Perkins Silk Shop informed prospective customers, “lingerie material is always acceptable as Xmas gifts.” The Municipal Gas Company pushed husbands to buy their wives “an easy electric washer” to “make her happy Christmas morning.”

Few town stores advertised Christmas gifts with some exceptions. Altamont Pharmacy could provide the shopper with “Xmas Presents Acceptable to All Members of the Family” including electric tree lights for $4, Kodak cameras, candy, stationery, as well as electric flat irons and a vacuum cleaner for $50.

Fredendall’s Furniture Store had “Shopping Hints for Christmas Gifts” with suggestions of various pieces of furniture. M.B. Keenholts offered a variety including Christmas cards, decorative paper items, candy including ribbon candy and candy canes as well as the usual cigars and newspapers. And oddly, he also had select oysters should you want them.

Don’t forget The Altamont Enterprise, suggesting a year’s subscription for $1.50 would make a perfect gift, especially for a friend or relative out of town.

No Cyber Monday? No UPS, FedEx, Prime? A century ago, at-home shoppers would reach for “The Thrift Book of the Nation,” their Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog; fill out the order form; write out a check or more likely get a money order at their local Post Office; and wait for their mailman to deliver their package to their house unless they had a Post Office Box and had to pick it up themselves.

Charity

The poor in Albany weren’t forgotten. Various churches, either as a whole or one of their organizations, collected money or donations of food, clothing, and toys to be sent into the city.

St. John’s Lutheran Church sent a large amount of food, clothing, and toys to C.R. Story Mission while Altamont Reformed Church’s Laurel Band group packed a Christmas box to be sent to the City Mission in Albany.

In Guilderland Center, the Reformed Church requested apples and jelly to be sent to Dr. and Mrs. Griffin of Albany for their excellent work among the poor.

Each year, there were similar collections. Anything done for families or individuals in Guilderland who were having a rough time of it would have been done privately if at all.

Children celebrate

For the town’s children, Christmas was likely to be the most exciting time of the year with parties at school and Sunday school often with visits from Santa, refreshments, and gifts. Often these were combined with some kind of performances by the children — singing, reciting, and acting in plays with the public invited.

At Guilderland Center’s Cobblestone School, Mrs. Witherwax’s students “presented a pleasing program of Christmas songs, recitations, and exercises.” Afterward, there was a “merry Christmas party” when she presented gifts to the students from under the branches of the decorated Christmas tree in the corner of the room.

These school Christmas programs open to the community were common, sometimes combined with a party, other times strictly performances with class parties back in their classrooms. This was the case with Altamont High School where all grades from primary through high school offered an evening performance for families and friends of the school.

Not only did it seem that teachers gave children small gifts, but teachers received gifts from their students. Mrs. Witherwax went home one year with a clothes basket of gifts while Miss Lucy Osborn, the teacher at Dunnsville’s school, received a “fine hardwood rocking chair” from her “scholars.”

Occasionally these public Christmas programs were presented at local churches as when the Parkers Corners school children offered their community Christmas program at the Parkers Corners Methodist Church.

In Guilderland, the public-school classes combined with the Federated Sunday School classes to present a community program at the Guilderland Methodist Church. Afterward, Santa arrived with candy and oranges for all the children while Sunday school teachers gave additional gifts to their own classes.

Children who attended the town’s Sunday schools usually put on programs of recitations, music, and stories for their own congregation in combination with a party following, a visit from Santa, and gifts from their Sunday school teachers.

Usually adults of the congregation were invited to view the performance and join in the party afterward. These performances were a method of informally teaching children about the real meaning of Christmas.

Church services

The town’s Protestant churches held their special Christmas service on the Sunday preceding December 25 unless as happened in 1921 when Christmas was actually on a Sunday.

Whatever the actual day of Christmas, during their Christmas service choirs sang, sometimes there was inclusion of Sunday school children singing a carol or giving a recitation, and also a Christmas sermon given by the minister, making it a special Sunday.

Helderberg Reformed Church had just purchased a new organ and its special Christmas service began with an organ recital. Sometimes on Christmas Eve or Christmas night a church may have held a special service also.

A special vesper service, held in Altamont’s Reformed Church for their Sunday school centered around “White Gifts for the King,” when each Sunday school class brought up gifts of toys, clothing, and other articles including money to be distributed to the poor.

And new in 1923 was the announcement, “Christmas Masses.” Rev. Walter T. Bazaar would be offering Mass at 7 a.m. at St. Lucy’s on Christmas morning before turning around to return to Voorheesville to offer two additional masses at St. Matthew’s.

Community

By 1923, technology made its appearance with The Enterprise listing Christmas radio programs offered on Schenectady’s WGY, the variety including a broadcast of the service at St. Peter’s Church in Albany and the WGY Players acting in the Christmas-themed play “The Fool.”

During these years, Guilderland Center had a civic group that put on a community Christmas party at the “Town Hall,” a building on the community’s Main Street, owned by the town of Guilderland, which had a large meeting room used for community events.

Everyone in Guilderland Center and the nearby area was invited. The evening began with a “cafeteria” supper — one year oysters made up the main course — with games for the children who also usually repeated the program they had performed earlier at the Cobblestone School.

There was an electrically lighted Christmas tree and sooner or later Santa showed up with gifts for the children. Finally, the evening ended with dancing for the adults. This gathering occurred during the week after Christmas.

For those who were grieving recent loss, deeply depressed, in bad economic straits, or an unbeliever, December must have been a difficult month; but for the great majority of Guilderland’s residents, Christmas seemed to be a wonderful, community-oriented time of the year — a century with real spiritual meaning for a great number of them.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

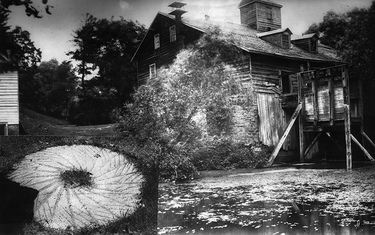

This photograph of Batterman’s Mill seems to be taken from the rear. In the lower left is an insert photo of a mill grindstone that could have actually been used in that mill. Note the groves in the mill stone, which would have required annual dressing to keep them functioning properly. This would have been one of two, one on top of the other to do the grinding.

At frequent intervals along Guilderland’s main roads, gas stations appear — not striking architecture but they serve a useful, necessary purpose for those who continue to drive cars with combustion engines. The same could be said of 19th-century grist mills, not particularly impressive, but necessary in their day to serve Guilderland’s large farm population if families, animals, and fowl were to be fed for the year ahead.

In 1845, for the first time, New York State conducted a state census, not only of population, but agricultural statistics as well as business information. At that time, Guilderland had two grist mills.

One was the Globe Mill on the Normanskill at Frenchs Hollow and the other was Batterman’s Mill on the Hungerkill in Guilderland where the stream was crossed by the Western Turnpike. Both mills operated by water power. Decades later, in the 19th Century, they were joined by a third mill in Altamont powered by steam.

In about the year 1800, coinciding with the opening of the Great Western Turnpike, George Batterman leased sizable acreage from the Van Rensselaer interests. He dammed the east and west branches of the Hungerkill where they joined together to create a large mill pond on the north side of the turnpike.

A sluice to carry the water ran under the turnpike to power the large mill opposite on the south side of the road. His mill combined the functions of a grist mill, plaster mill, and satinet factory to manufacture a cloth combining wool and cotton thread.

The mill was finally taken down in 1899 and its last year of operation isn’t known. Today, the level of Route 20 has been raised many feet higher than it was in the early 1800s and the sizable mill pond is now silted in, making it difficult to imagine the original mill site.

During the last years of the 18th Century, the rushing waters of the Normanskill at Frenchs Hollow were dammed and water was sent through a pipe into the mill to turn the water wheel, reputed to be 24 feet high although it’s possible that this early mill wasn’t as large as the mill had become in its later years.

The dimension of the mill wheel was cited in a 1932 article appearing in the Knickerbocker News, perhaps using as the source someone who could still remember the old mill in operation. This was also a dual-purpose mill with woolen cloth produced during the off season when there were no grains to mill.

At some point during the 19th Century, Elijah Spawn took over the mill and operated it with his son until the end of that century when he leased it out. On the 1854 Gould Map of Albany County showing Guilderland in detail, the site is marked Globe Mill, but a few years later, on the 1866 Beers Map, it is marked E. Spawn.

In 1896, Spawn leased the mill to Wesley Fuller, and it is not clear when the mill last operated. The property itself remained in Spawn hands until 1915 when the Watervliet Reservoir was being established.

The 1854 Gould Map also shows Normanvale Mills on the Hungerkill near where it flows into the Normanskill. Although the New York State 1845 Census mentions that only two grist mills operated in town, it’s possible these were just saw mills at this location also. The 1866 Beers Map shows only a saw mill here.

Few details of mill operation in Guilderland in the early decades of the 19th Century are known but, as Guilderland was a rural farming community, and of necessity families had to be self-sufficient in that era, the grist mills must have been very busy at harvest time, grinding grains into flour or meal to feed farm families and to produce feed for their animals and fowl.

Late 1800s

The later years of the 19th Century are more thoroughly documented. Once The Enterprise began publishing in 1884, it became possible to get some closer glimpses of Guilderland’s mill operation.

In Altamont, Adam Sand began operating a steam-powered grist mill, probably in the 1870s or early 1880s with his sons. In 1885, they announced they were ready to resume business after having completed repairs on their steam mill.

The next year, they let readers of The Enterprise know that they had acquired a corn sheller that would remove corn from the cob at no charge. Tragically, Adam Sand was killed in 1890 by an exploding mill stone.

A year later, his sons expanded their mill and then, in 1895, they erected a new building at Park Street and Fairview Avenue. A year later, the mill was sold to John H. Ottman who ran the mill until his death in 1905 when Miles Hayes took over, running the mill until it burned in 1928.

By the late 1800s, large-scale wheat-growing and milling had moved to the Midwest, but the local mills continued to have much business grinding rye, oats, corn, and buckwheat grown on the town’s farms until the early 20th Century.

“The grist mill of E. Spawn & Son is running day and night in order to grind the pancake timber,” that being buckwheat. “The crop is reported huge, flour selling at $2.25,” wrote the Enterprise Fullers columnist in October 1884.

A few years later, Spawn’s mill was doing a “lively business running day and night.” The same was said of Sands & Sons Mill, running day and night several different Octobers, which seemed to be the mills’ busiest time, both mills producing “pancake timber,” the local term for buckwheat flour.

Buckwheat was a very important local crop and breakfast staple of that day, and by the late 19th Century, the single most important output of the two mills. Buckwheat, a crop brought in by the Dutch in the 1600s, was easy to grow, a prolific producer even in poor soil, and very nutritious. It was widely grown in this area.

Economics

Mill owners earned their profits from either being paid in cash or in a percentage of the grain being milled, which they then resold. Spawn advertised that his standard horse feed was available for sale at several local general stores such as P. Petinger’s in Guilderland Center and Van Allen & Quackenbush in Fullers.

At the same time, he offered to pay for buckwheat and flour ground at his mill temporarily and advertised they would do custom feed grinding “for either cash or toll.”

Mills required maintenance to continue. It was noted at various times that both Spawn’s mill and Sands/Ottman mill were doing maintenance on their mills and would close down for a few weeks in the off season.

Mill stones required someone to “dress” them by having the grooves recut to allow the grain to be ground properly. It was noted at the death of John Batterman, the last Batterman owner of the family mill, that his mill hadn’t been brought up to date with the changes in milling, leading to a premature end to its operation.

John Batterman, owner of the Batterman’s mill for several decades, had been a very prosperous businessman, running his mill and operating a feed store in Albany, even serving as a trustee of Albany City Savings Institution.

By the 1890s, he had fallen on such hard times that his mill was sold at foreclosure for $5,500 in 1892. A year later, he was arrested after being caught red handed in Foundry owner Jay Newberry’s barn pilfering oats. He ended his days in the Albany Home for Aged Men, dying in 1902.

The author of the Enterprise’s “Guilderland” column sadly marked the 1899 demolition with a nostalgic final farewell: “Adieu, Thou was once so great and powerful and that hath prepared the staff of life for untold thousands. Thou hast outlived thy usefulness…”

This final goodbye could have been applied to each of our town’s grist mills as they closed down. In the years ahead, with the rapid development of electric vehicles, our town’s gas stations may eventually go the route of those long-ago grist mills.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

The charter members of the Guilderland Center fire company posed in front of their original firehouse in the “Old Town Hall” on the hamlet’s main street. The Village Queen is the piece of equipment on the left, which repaid its cost of $1,350 many times over, last used at a blaze in 1951. Note that it had to be towed to fire scenes. It is now the department’s parade piece.

Was it a lighted cigar tossed by a member departing the April 29, 1886 Good Templars’ meeting at their rooms that caused the village’s worst and most destructive fire?

At that time, the west side of Knowersville’s Church Street (now Altamont’s Maple Avenue) was lined with businesses: a tinsmith and hardware store, shoemaker, drug store, blacksmith, woodworking shop, harness maker, and carriage factory.

The Noah Masonic Lodge and the Good Templars, a temperance organization, met in rooms above businesses in two of these buildings.

Flames, suspected of erupting in the hallway or stairs near the Good Templars’ rooms, spread rapidly to sheds in the rear, then from building to building along the street where “in a short time the whole block of frame buildings was one mass of roaring flames.”

Once the alarm was given, men quickly came running with buckets and dragged the little hand engine owned by the community to the scene but, with no adequate water supply nearby, their efforts were fruitless. All was lost with the estimate of damage being $20,000, a huge sum in 1886.

Within a few years, after Knowersville had been renamed Altamont, the village was incorporated and water mains installed. When, in 1893, Altamont Hose Company was established, it was said that the disastrous fire of 1886 helped to motivate the villagers to organize to provide better fire protection.

Large buildings, large losses

Among Guilderland’s large buildings of that day were hotels. Very well known and heavily patronized was Sloans’ Hotel on the Western Turnpike (approximately opposite the Schoolcraft House) in the hamlet of Guilderland. Around 1 a.m. on March 14, 1900, the owner awoke to the crackling sound of a rapidly spreading fire, forcing him, his wife, and daughter to jump out of a window in their nightclothes, fleeing to their neighbors’.

The church bell was rung to sound the alarm, arousing the men of the community to come running with their buckets, hopeless against the raging flames in the 60-year-old structure, Thought to have begun in the cellar kitchen, this fire ended the history of a popular hotel. The loss was $6,000.

The other large structures of that day were the feed and grist mills serving the farmers of the surrounding area. Miles Hayes’s huge feed and grist mill adjoined the D & H tracks at the corner of Altamont’s Park Street and Fairview Avenue.

Late one afternoon in 1909, the discovery of fire in the third floor of his mill quickly brought out members of the Altamont Hose Company who played two streams of water on the structure. Fortunately for Hayes, the firemen had recently acquired a heavy section ladder that reached up to the third story capable of bearing the weight of two or three firemen holding a water-filled hose.

Pouring water into the window at the end of the building extinguished the flames, halting them from spreading, but in the process destroyed large quantities of grains, animal feed, and machinery. Insurance covered Hayes’s losses.

New companies

McKownville and Guilderland Center each established their own fire companies in 1918, commencing fundraising to purchase equipment. The year before the Witbeck Hotel, originally the McKown Tavern, had burned, motivating McKownville to establish its fire department.

In 1924, Guilderland Center had the foresight to acquire the Village Queen, a pumper powered by a Model T engine capable of shooting two streams of water up and over a three-story building.

Guilderland Center was the scene of the next huge fire when, in August 1926, the three-story former Hurst feed and grist mill located near the West Shore Railroad tracks went up in flames.

Described as a “spectacular blaze,” it could be seen for miles around, attracting hundreds to the scene. Guilderland Center called in Altamont and city firemen to deal with the huge fire.

The mill and an adjoining building were empty, due to be moved across the road because they stood in the path of the planned overpass bridging the West Shore tracks. The two buildings were a total loss, but firemen saved the nearby railroad station and hotel. No cause of the fire could be determined.

Next to burn was the Guilderland Center hotel that had survived the adjacent mill fire only months before. The building was under new ownership, but had not reopened.

Firemen had to run hoses out to a pond near the West Shore tracks for a water supply, causing a delay in dousing the hotel fire. The building was a total loss to its new owner, but its sheds, stable and hotel garage were saved. Again, no cause of the fire could be determined.

Pumper needed

The old Hayes Mill in Altamont, which had narrowly escaped destruction in 1909, was now operated by Fort Orange Feed Stores Inc. One evening in December 1927, a fire, possibly originating in the boiler room and spreading rapidly, had already made much headway by the time a bypassing resident noticed it.

In spite of quickly responding and aiming three streams of water at the building, the Altamont Hose Company was unable to put down the flames. The Guilderland Center Fire Department arrived towing the Village Queen, which was able to direct two forceful streams of water up and over the building.

Even this was not enough to quell the inferno. By midnight, the building was a total loss. Fortunately for the village of Altamont, the winter night was exceptionally warm and there was no wind blowing.

The Guilderland Center firefighters earned praise in The Enterprise for their assistance, but questions were raised in the village as to why Altamont had never purchased a pumper for its own hose company. The paper also pointed out firemen wore their own clothes and, if ruined while fighting a fire, were expected to pay for their replacement.

Miss Jennie Wasson, a wealthy woman who owned a summer cottage on the hill, then donated money for gear for the Altamont firemen. The pumper question was still being discussed when the next big fire broke out in Altamont.

This time, the Altamont Hotel was ablaze. Smelling smoke, the owner evacuated his family and raced to his neighbors to turn in the alarm. Hose company members hurried to the scene to find the attic and third floor in flames, kept confined by the hotel’s metal roof.

Again Guilderland Center firefighters rushed the Village Queen to the burning building, pouring water on the roof and the area where flames broke through while inside Altamont firemen were trying to quell the blaze.

Finally under control, fire had seriously damaged the third floor and attic and the gallons of water poured on the burning hotel had drenched the remaining interior. The hotel’s metal roof kept the flames confined while the brisk wind blowing earlier had died down, preventing the fire from threatening the village with disaster.

The Guilderland Center Fire Department was thanked and praised in The Enterprise for responding to the request for help in fighting the March 1928 Altamont Hotel blaze so willingly, pulling the Village Queen, their powerful pumper, “no small favor when they come a distance of nearly three miles in the middle of the night to render assistance.”

It was very obvious that Altamont needed its own pumper.

Seminary burns

LaSalette Seminary, originally erected as the Kushaqua Hotel on the escarpment above Altamont, caught fire early on the morning of Oct. 25, 1946. Smelling smoke while at breakfast, the priests and seminarians, after discovering fire burning in the attic and third floor, quickly exited the building.

A combination of old wood, a shortage of water to effectively battle the blaze, and high winds all contributed to the venerable structure being consumed within an hour in spite of the efforts of firefighters from Altamont, Guilderland Center, Voorheesville, the Army Depot, and two trucks from Albany’s Fire Department.

Hamlet spared

A drought in the summer and fall of 1947 had left fields and hedgerows in the area tinder dry. Late one October morning, it was most likely a lighted cigarette butt tossed from a car window by a careless smoker along Route 146 east of Altamont that ignited a fast burning fire that came close to destroying Guilderland Center.

A furious west wind pushed a wall of flames toward the hamlet and Edward Griffith’s Fruitdale Farm situated just to the west. The conflagration covered an area one-quarter mile wide and raced like a wildfire, burning everything in its path.

State Police warned hamlet residents to be prepared to evacuate as flames 20 to 30 feet high bore down. Two-hundred men from seven fire companies and employees of the Army Depot lined up, managing to stop the flames just at the edge of the hamlet.

Fire Commissioner Joseph Banks later described it as “a ball of fire rolling toward the village.” Guilderland Center was saved through the strenuous efforts of the volunteer firemen and a plentiful supply of water from the nearby Black Creek.

Edward Griffin, owner of Fruitdale Orchard just west of the hamlet, wasn’t so fortunate. He lost two barns, over 1,000 fruit trees from his 30-acre orchard, farm equipment, a truck, and 2,000 apple-packing boxes. The only thing left standing was his house; everything else was lost.

Depot fires

The Voorheesville Holding and Reconsignment Point, then informally called the Army Depot (now the site of the Northeastern Industrial Park), has been the scene of three major fires.

The late Ella Van Eck, a World War II depot employee, remembered a huge fire in Warehouse No. 3, which burned a large supply of cots packed in flammable excelsior.

With no specific date, the details can’t be tracked down in print because of World War II censorship, although the Enterprise noted in an article about a later warehouse fire, that a major warehouse fire had occurred during the war.

When the United States Government constructed these warehouses in the early 1940s, the structures were 960 feet long and 190 to 200 feet wide, divided into four sections with firewalls separating the sections.

Discovered by a civilian guard on June 17, 1950, a fire in the south end of Warehouse No. 5 had apparently been blazing for some time, the firewall keeping it contained to that one very large section and confining most of the damage to that area.

Smoke rose 200 feet in the air with high winds driving flames 60 feet high, making the fire visible for miles around. This attracted hundreds of spectators who created a huge traffic tie-up on local roads.

The Army Depot had its own resident fire department, but controlling this blaze was beyond their capability and departments from Guilderland Center, Altamont, Voorheesville, Albany, and Schenectady were called in to give mutual aid.

The fire roared out of control for two hours and by the time it was finally out, $2,000,000 in damage was done to the warehouse and its military contents.

Sixteen months later, on Sept. 24, 1951, another major fire occurred at the Army Depot; this time, Warehouse No. 6 was completely destroyed. The fire was already burning out of control by the time it was discovered, so depot firemen quickly called in nearby departments from Voorheesville, Guilderland Center, Altamont, Westmere, McKownville, North Bethlehem ,and Albany’s Pumper No. 10.

As firemen were arriving on the scene, the warehouse roof collapsed and, not long after, the walls caved in. The blaze was brought under control in one-and-a-half hours, but water continued to be poured on throughout the night.

Soon after its discovery, just as the year before, a huge plume of smoke attracted many hundreds of curious onlookers who lined the depot fences and tied up traffic on local roads. Loss of the warehouse and material belonging to the Army Corps of Engineers was estimated to be $2,575,000.

More recent losses

After the huge 1927 fire at Altamont’s Fort Orange Mill, the site was rebuilt as a feed mill by W.G. Ackerman. The Ackerman Mill operated as one of the village’s prosperous businesses until Aug. 17, 1961, when in the midst of Fair Week, fire was discovered.

Believed to have started in the grain elevator, flames then raced through the office and feed-mixing and storage building, and within an hour the building was a $200,000 total loss.

Flames leaped 50 feet in the air with clouds of smoke and it was claimed that the plume could be seen as far away as Albany. Eleven fire companies fought the fire including Altamont, Fort Hunter, Guilderland Center, McKownville, and Westmere.

On the adjacent D & H tracks, a Walter Truck Co. crash truck sat pumping out 1,500 gallons a minute to prevent the flames from leaping the tracks to Ackerman’s coal and lumber yard on the other side.

Fortunately no wind was blowing; otherwise the neighboring Hayes House and other old houses on nearby streets and the fairgrounds, which backed on the Ackerman Mill property, could have burned as well.

As Altamont’s police chief said afterward, there were “catastrophic possibilities.”

Guilderland Center’s Helderberg Reformed Church was the victim of an arsonist on March 26, 1986 when he poured accelerant to start a fire that fully engulfed the historic structure. The fire was noticed by passing motorists about 10:30 p.m. and had a good start by the time firemen arrived.

Seven fire companies assisted the Guilderland Center Fire Department in bringing the fire under control. Spreading rapidly through the old, open building, when the flames reached the taller bell tower, the bell gave out one loud peal. By morning only a shell of the building remained.

The congregation was forced to demolish the remains and build a new church on the site. The arsonist was arrested and sentenced for his act.

Guilderland residents and businesses have been grateful for the protection provided by our volunteer firefighters beginning in the 1890s with the formation of Altamont’s Fire Department. These volunteers respond to our calls any hour of the day or night and deserve our thanks and support.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

A notice in the July 18, 1862 edition of the Albany Evening Journal reported that Prospect Hill Cemetery had appointed “a committee to solicit subscriptions for the purpose of erecting a suitable monument to be placed in said plot off ground.” The cemetery had set aside land for the burial site of any soldiers in the County of Albany. Once erected, names were inscribed on the lower part of the monument which still stands today although the bronze eagle has long since disappeared.

“Started for Dixie” recorded Abram Carhart in his new diary on March 16, 1863. A fever had prevented him from leaving Albany with his regiment, the 177th New York State Volunteers, on Dec. 16, 1862.

After the regiment’s arrival on Jan. 11, the men had been assigned to the Army of the Gulf, one regiment of the 20,000 soldiers under the command of General Nathanial Banks. Carhart would eventually join them, his diary giving us a vivid picture of how grueling, dangerous, and yet boring it could be for an individual soldier on campaign.

Abram Carhart, the son of Sanford and Sophie Carhart, grew up on a family farm likely located on (West Old) State Road and attended the local one-room school. Methodism, thriving in Guilderland at this time, attracted young Carhart who became a member of the State Road Bible Class and formally committed to the Methodist Episcopal faith.

Carhart was eager to volunteer when the Civil War broke out but his mother’s objections kept him in Albany, serving in the 10th New York Militia. However, in September 1862, the 10th Militia became the 177th New York State Volunteers, a nine-month regiment.

Civil War volunteer regiments, raised by the individual states, served for varying amounts of time up to three years. Each regiment was made up of 10 companies of 100 men each. Usually the volunteer regiments included many men from the same area who knew each other before joining so that there were several men from Guilderland serving with Abram Carhart who was assigned to Co. C.

After several medical extensions, Carhart was finally sent to New York City, reporting to Governors Island where his life as a soldier really began. His days were taken up with drills and picket duties with a bit of free time for religious services and letter-writing.

Soon to ship out to New Orleans, on April 6 he wrote, “changed drawers and stockings,” the first of three mentions of changing his drawers during the four months his diary covers.

On April 8, he put out to sea, destination New Orleans. About 75 miles from shore, a brig collided with the ship he was on, forcing its return to Governors Island.

Three days later, Carhart again sailed. In spite of some rough seas and sea sickness, he noted when Cape Hatteras was passed.

Big excitement came when a rebel blockade runner was fired upon and captured, carrying 22 bales of cotton, probably heading to England. Sailing past the Florida coast, Carhart was fascinated with the lush green vegetation along the shore.

At last, the Mississippi was reached April 21, his ship arriving at New Orleans the next day. Not immediately being sent to report to his regiment, he took the opportunity to “change shirt, drawers & stockings last night.”

He noted that the Provost Guard was “arresting a good many deserters” and that “the cake ladies were drove out for bringing liquor to the soldiers.”

A few days after his arrival, Carhart joined his regiment at Camp Bonnet Carre where he found fellow Guilderland farmboy Peter Ogsbury sick, but the rest were well. Whenever he encountered someone he had previously known from home, he noted it in his diary.

That day, he “wrote home to Ma,” and probably the news of Ogsbury and the rest would have been included. Since arriving at Governors Island, Carhart penned many letters during his service, having already written seven, as noted in his diary.

The U.S. Post Office with the Union Army did an amazing job of carrying mail and packages back and forth, even during campaigns, although it sometimes took time. Even during the campaign against Port Hudson, a package even arrived for Carhart.

Because almost all Union soldiers had attended at least one-room schools, except for many immigrants, they were literate to some degree and their surviving letters and diaries provide the troops’ view of the war.

Shortly after his arrival, Carhart and the others in his regiment were “mustered in for pay.” A regiment would stand at attention while attendance was taken, the list sent to Washington, and eventually the men received their monthly pay of $13.

Using information from Carhart’s diary, it appears there was an underground economy in which the men borrowed, loaned, sold, or purchased from each other between pay days. Carhart loaned Abram Bradt 10 cents and Billy Tygert 25 cents and repaid $2 to P.J. Ogsbury and money owed to Henry Swan.

Carhart sold 50 cents worth of tobacco to A. Fox who “promised to pay when in camp” and a few days later sold 50 cents worth of tobacco to Billy, with an illegible last name, who also would pay back in camp.

Breaking Confederate

hold on the Mississippi

The 177th had joined thousands of other soldiers seeking to break the Confederate hold on the Mississippi. To do so meant Union troops must take the two well-fortified points on the river, Port Hudson, a few miles north of New Orleans, fortified by dug breastworks and a battery of artillery, while 242 miles to the north was Vicksburg, the Confederate’s most powerful stronghold on the Mississippi.

General Grant’s army was slowly working its way toward Vicksburg and then besieging it. Simultaneously, General Banks was attempting to capture Port Hudson. Much action lay ahead for the 177th.

Once back in his regiment, Carhart almost immediately went into alert when at midnight everyone was called out and “formed a line of battle.” Apparently a false alarm, later the next day he was on guard duty, the first of many times when he “felt a sample of southern mosquitoes while on picket.”

Soon orders came to leave camp. Carhart and his company steamed upriver to Davis Plantation where they had breakfast coffee, next marched eight miles until dinner, then 12 miles to McGills Ferry.

The next night, soldiers were called into a battle line, Carhart having picket duty. May 10 and 11 were quiet days, but the next day several of them were fired on by rebels, “one man wounded & four men hit.”

Departing from McGill’s Ferry, the men marched four miles through dust and swamps 12 miles until eating a dinner of “chicken, geese and such as we could get.” Along the route, the Union soldiers were foraging, helping themselves to whatever they could gather up along her way.

The next day, four companies were sent out, “capturing in all about a dozen horses, a lot of cotton, a hogshead of molasses & a lot of sugar.” Stripping families of their livestock and food supplies along the line of march was common, resorted to by both Yankees and Confederates.

Having been on picket duty under the threat of attack, once off duty Carhart returned to camp, still with enough energy to sell tobacco to two comrades for 50 cents each. Finally, they left McGill Ferry at midnight, marched until seven the next morning, having covered 22 miles in seven hours.

After a rest until 4 p.m., the regiment marched about 12 miles until 11 p.m., receiving their first ration of whiskey, often given out to Union soldiers from the Commissary before or after a particularly demanding time. A day later, the men reached Baton Rouge.

Resting a day, Banks’s men crossed the river, marching 17 miles north toward Port Hudson. Then they marched from 10 a.m. until 6 p.m., forced to “lay down for the night on the wet ground for it had rained for a while.”

The next day, Co. C was detailed to build a bridge that took all day, then marched about one-and-a-half miles after forming a line of battle. Leaving their encampment the next day, the men encountered an enemy fort.

They were ordered to march on the double quick across a field about a mile under rebel fire the entire time. The Union soldiers withdrew to the river to communicate with Union gunboats there, but when they returned, the Confederates “had got the range, wounding three with one man in Co. H having to have his leg taken off.” They returned to a camp about two miles from Port Hudson.

A welcome day of rest was followed by a frontal charge on Port Hudson. The 177th was ordered to support the 21st Indiana Battery, an artillery unit with 20-pound mortars. “In the forenoon,” Carhart wrote, “Companies F & H were detailed as skirmishers & Co C was left with the battery while the rest of the regiment went to the center to support the charge.”

The attack was a failure. Port Hudson remained in Confederate hands. Back in camp, Carhart received two letters and another ration of whiskey.

One day, Co. C went out as skirmishers, the next on picket duty, happy the next day to be relieved by the 6th Wisconsin. A few quiet days then several companies of the 177th including Co. C were ordered out to build breastworks.

That meant digging trenches, a project that kept them busy for several days including “planting” mortars. After several days of hard labor, Carhart noted, ”finished the rifle pits today.” This was followed by another day of picket duty within 600 yards of the rebel fortifications, shooting 15 rounds.

On June 14, Banks ordered another frontal attack that again was a futile assault. Carhart’s terse entry read, “rec’d marching orders at last night about one o’clock to go to the left, left camp about 3 o’clock — got to the left about 5 o’clock. — shot and shell came rather close for comfort, so moved a little farther and waited for orders.”