φαίνεταί μοι. If that’s Greek to you, you’re correct, it is. And if you detected they are the first two words of the great Seventh-Century, Lesbos-born, Greek poet Sappho’s Poem 31, you are correct as well. It translates “He seems to me . . .”

It is Sappho’s most famous poem, an epithalamium, a wedding poem sung for a bride on the way to the marriage chamber.

The poem — or more correctly song because Sappho plucked a lyre (barbitos) while she recited — is quintessential Sappho and deserves the attention of not only poets but every living soul since Adam and Eve because it touches the feelings of a heart experiencing loss of a beloved.

In Poem 31 the singer, poet, lyricist — it could be Sappho or a projected other — is expressing feelings of jealousy because a woman she loves has gone off and married someone else, a man. The loss is so great, the poet says, she’s broken out in a cold sweat and shaking, her symptoms so acute she feels dead.

This ancient torch song contrasts greatly with the same theme country music stations play every day of the year but Sappho sings with more authenticity, immediacy, and accuracy of feeling. The listener cannot escape experiencing the pathos of the singer, thus the poem becomes a mirror for the listener’s soul.

And while our lesbian poet reveals she is in the throes of death, she tells her story “slant,” as Emily Dickinson commanded, so the reader does not feel Sappho — or whoever the projected singer is — is one of those 19th-Century repressed “hysterics” who came to Sigmund Freud in hopes of jettisoning sorrow.

Sappho was among the first Western literary ancients to address the world in the first-person, and the first to do so with such outright candor, without shame or malice, which is what every human being beset by loss desires, especially when laced with jealousy.

Because of her depth of insight, the ancients adored Sappho. They said she was as great as Homer, calling Homer “the poet” and her “the poetess.” Plato called her the “10th Muse.”

Her image was engraved on coins in Lesbos; a beautiful statue honoring her was erected in the town hall at Syracuse; elegant vases depicting her plucking a lyre were cast only two generations after her time for which cultured, well-to-do Greeks paid good money to display in their homes. It may not be too much to say she was an ancient rock star.

When the Athenian statesman, lawmaker, and poet Solon heard his nephew sing a song of hers at a drinking party, so enchanted was he, legend says, he asked the boy to teach it to him. He said, once he learned it, he would be able to die.

Long-time fans of Sappho are elated these days because the bard is back in the news. Last year, Dirk Obbink, a papyrologist at the University of Oxford, revealed he had been the recipient — secretly from a private collector — of two previously unknown poems of hers: one about her brothers, the other about unrequited love.

The finding of the “Brothers” poem was especially lauded because it makes only the second complete poem we have of Sappho; the other is called “fragment 1,” a hymn to Aphrodite, where the singer beseeches the Greek goddess to aid her in her pursuit of a woman she’s after (religion as an aid to libido-satisfaction).

Scholars are indeed grateful for anything “Sappho” that comes along because 97 percent of what she did is gone; her extant work consists of little more than 200 fragments of poems, a considerable number of which amount to no more than a line or two. It’s maddening. The greatest shame is that cataloguers in the ancient library of Alexandria said Sappho had nine books of poems to her credit amounting to more than 13,000 lines!

Whatever happened? You will find it written all over the Internet that those verses vanished because Roman Catholic officialdom burned her in disgust. The Byzantine archbishop Gregory of Nazianzen and Pope Gregory VII are always mentioned as the sanctioning culprits, but there is no evidence to support condemning them.

It is known, however, that the Second-Century ascetic and Christian theologian Tatian in his address to the Greeks (Oratio ad Graecos) called Sappho "a whore,” a whore “who sang about her own licentiousness.” But that fellow must be relegated to nutdom because he said that marriage was the institution of the devil.

The reality seems to be that Sappho’s work fell on rocky soil in large part because she wrote in a difficult vernacular Lesbian-Aeolic dialect that differed from the lingua franca of Athens at the time, so later copyists selecting books to transcribe triaged her to the trash in the interest of time and limited translation skills.

A new translation of Sappho appearing last year by Grand Valley State University (Michigan) Professor Diane J. Rayor (with introduction by André Lardinois) titled “Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works” helps to assuage the ignominy of such (idiotic) shortsightedness.

Rayor’s efforts have been lauded in all the scholarly mags (Lardinois’s introduction as well) but the nuances of her translation keep being compared to those of the laser-minded Greek scholar and poet Anne Carson in “If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho,” which appeared a dozen years ago. Vis-à-vis Carson, Rayor always seems to finish second.

Sappho said a poet can sing about wars and all that tough-guy stuff but what matters most is where a person’s heart is. In Poem (fragment) 16 she says (Carson’s translation):

Some men say an army of horses

and some men say an army on foot/

and some men say an army of ships

is the most beautiful thing/

on the black earth. But I say it is/

what you love.

Because she came from Lesbos and had an abiding affection for women — though she was married and had a daughter — during the latter part of the 19th Century women whose feelings of love were directed toward other women began to call themselves “lesbian.” The Greek verb lesbiazein (to act like the women of Lesbos) has highly erotic connotations and those interested in divining them can check their Liddell and Scott rather than expect explication in a family newspaper.

Sappho was exiled during her twenties or early thirties — depending on her actual birth year, which ranges from 630 to 612 B.C.E. — at a time when Lesbos was undergoing great political turmoil but no evidence exists to suggest she was politically involved.

And the erotic themes she sang about were not outlandish in any way. That judgment came during the Hellenistic period (third/second centuries B. C. E.) when what she said was regarded as disgraceful for a woman.

For those interested in exploring the mansions of the human heart, Sappho is cherished all the more because her few remaining texts keep out of reach like the apple she sang about in Fragment 105A (Carson translation):

as the sweetapple reddens on the high branch

high on the highest branch and the applepickers forgot —

no, not forgot: were unable to reach.

But there is hope. Each unearthed papyrus, in which her words were sealed for over 2,000 years, enables the yearning heart to tiptoe a bit higher and just reach the sweet red apple of sapphic love.

Just as there’s a difference between baseball players and people who play baseball, so there’s a difference between gardeners and those who garden.

Those who say, “I think I’ll throw a few tomato plants in this year” are not “baseball players,” telling us in code they’re not interested in watching things grow. And, though differing at the genus-level, growing a plant is no different from raising a child.

Therefore I have rules and views about gardening. The first is: The way a person’s garden looks is the way that person’s inner landscape is, in shape and content.

When a garden is helter-skelter, that person’s mind is helter-skelter. Gardeners might be forever catching up on things that need to be done, but are never slipshod about what sits before the eyes.

Which means that, since each plant has its own growing needs to enjoy its stay on Earth, before growing a plant, the gardener finds out about it, especially wanting to know what other gardeners have said about it.

Growing kale is not growing potatoes or laying an asparagus bed and growing any sort of thing does not mean dousing it with Miracle-Gro. The gardener is, as the person who grows things is not, interested in fostering conditions that insure diversity.

And let me add that people who say they hate weeding are not gardeners. I am amazed at the number of weed-whiners, people who act as if they’ve been besieged by an unhealing rash on a sensitive part of their body.

First of all, weeding is healthful for gardener and plant alike. For the gardener, it’s meditative, restful, and contemplative. It slows the city in us down and curbs the ADHD in everyone.

When Cicero was defending the Roman poet Archias in 62 (BCE), he told the prosecutor Gratius why Archias was so important to Rome: “You ask us, O Gratius, why we take such great delight in this man. Because he supplies us with a place where our souls might be refreshed from the din of the marketplace, and our ears weary from its clatter find some peace of mind.”

Cicero could have been talking about weeding and gardening generally. Weeding refreshes the mind by allowing the ears to breathe freely; the process of thoughts-arising as we move from bed to bed instructs us in a hundred different ways.

And because the gardener is attentive to the livability-quotient of each plant he is ready to do battle with any being that diminishes it.

I’m not saying pull every weed as if you’re intimate with it — there may be large sections to clear — but that “killing a weed,” “taking it out,” “neutralizing it” with precision requires attentiveness to its demographics.

Some weeds burrow deep into the ground and taking off their heads breeds gorgonesque effects. They threaten like Arnold Schwarzenegger in “The Terminator”: “I’ll be back.” The gardener’s bible says: Know thy weeds; they will be back; be prepared.

The meditative aspect of weeding ought not be minimized. It induces endorphins. When the mind sees the cultivated plant more relaxed, freed from invading hordes, the gardener relaxes too, feeling that something has been done to promote livability (the plant’s and ours from its fruition).

Mutatis mutandis, in a day or two the freed plant will be less constrained and the vigilant gardener — a redundancy of course — will record that transition, if not in a book, mentally — in gardening terms indelibly.

A good training ground for learning this vigilance is starting plants from seed, maybe upstairs in your room after winter’s done. And not to decry the efforts of those who do “the windowsill thing,” lights are essential. It’s strange but plants are more accepting of our diversity than we of theirs.

Starting life from seed, the gardener learns how to make a home, how to hydrate, how to feed a being trying to get a leg up on life.

The great tomato aficionado Craig LeHoullier says in his just-released “Epic Tomatoes: How to Select and Grow the Best Varieties of All Time” (Storey Publishing) he feeds his seedlings nothing — contrary to the wit of most — because today’s potting soils are fully fit.

It’s a great book; if you are a tomato fan, get it, study it; I have problems with aspects of its design but the content is far beyond a 100-percent solid. He and Carolyn J. Male are the best there are, though she talks about tomatoes in a way that enraptures me.

The last thing I’ll say about method has to do with successive plantings. If green beans are a favorite (bush, say), you’ll need to plant a row every 10 days. I’m surprised at how many people treat growing as a one-shot deal.

And, in terms of planting lettuce, we have nearby greenhouses such as Gade’s and Pigliavento’s to get us an early start, so there’s no reason to buy lettuce from late May to late October — and infinitely better tasting than any store-bought.

And because the gardener refuses to let winter have the final say, toward the end of summer he counts back from the first frost and plants accordingly what the family likes, well aware that peas planted in early August present a different set of rules from those set out in April.

My father knew this; he was a gardener. He cut grass for rich people on weekends and took care of their flower beds but in our backyard, the size of a postage-stamp, he had fruit trees from upstate nurseries producing five kinds of apples on a single stem.

Once when I was a kid he asked me to go to the library with him at night; he had a horticultural question to review. I saw him in the reference room wrapped in silence seated before tomes on a large oak table in another world. He had an aura.

That day (night) I fell in love with gardening. I had my own when I was 18 and living in a monastery, a whole other world under a whole other set of circumstances, but his other-world devotion stayed with me.

Each day when I go to weed and support the conditions of life, in some way my father is with me and I keep in mind my first garden when my soul was freed from the din of the marketplace and my mind from the clamor of its death.

Oh, and for the record, any gardener I know is beyond happy to hear anyone say at any time, “I think I’ll throw a few tomato plants in this year.”

Anyone anywhere who has an interest in attending to living things we’ll take. That is the nature of us gardeners.

Location:

“Secularism is not an argument against Christianity, it is one independent of it,” according to George Holyoake, the 18th-Century British writer who coined the term. “Secular knowledge is manifestly that kind of knowledge which is founded in this life, which relates to the conduct of this life, conduces to the welfare of this life, and is capable of being tested by the experience of this life.”

It’s referred to as the “American secular movement.” What it refers to is the deep dissatisfaction of a fast-growing number of Americans with official religious values and the institutions that oversee their observance.

Identified among this disaffected horde of non-traditional believers — let us call them that for now — are atheists, humanists, freethinkers, agnostics, Unitarian Universalists, pagans, and other categories of not-formally-religious and non-theistic Americans.

A report published by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life in October 2012 said one-third of adults under 30 call themselves “religiously unaffiliated” and in the five years prior to the publication of that report the so-called “Nones” increased by a percentage point a year.

It’s a phenomenon that has not gone unnoticed or without concern and comment by a wide range of interested parties, and for a diverse set of reasons.

During the spring semester of this year, Douglas Knight, a professor of Hebrew Bible and Jewish studies at Vanderbilt University, is teaching a course called “Secularism” in which 29 of his colleagues are involved as guest lecturers to explore what’s occurring in the United States with respect to the shifting axis of moral values.

Four years ago, California’s Pitzer College established a once-inconceivable Department of Secular Studies where students can major in different aspects of “secular studies” under the direction of Professor Phil Zuckerman and his departmental colleagues.

In his 2014 “Living the Secular Life: New Answers to Old Questions,” Zuckerman set out to explore the parameters of the movement as well as divine how “believers of another sort,” defined as atheists or agnostics by traditional believers, can be as giving, and “self-sacrificing,” and committed to community as the most traditionally religious devotee. And without pietistic rigmarole.

Zuckerman makes clear that many people who have adopted humanist values and ethics do not have an ax to grind with (formal) religion. They are more interested in understanding the fact-based foundations of their own beliefs and how those beliefs continue providing support in meeting life’s challenges with propriety and dignity.

Paul Kurtz, the late professor of philosophy at the State University of New York at Buffalo, who is recognized as “the father of secular humanism” long ago warned that, when formal religious beliefs and practices no longer hold meaning for a person, that person’s aim ought not to be bashing them and the people who live traditional religious lives but rather to find out how to proceed with his or her own life with meaning.

In an interview with The New York Times in 2010, Kurtz said, “Most of my colleagues are concerned with critiquing the concept of God. That is important, but equally important is, where do you turn?”

In 2009, Kurtz resigned from the board of the Center for Inquiry, a group he founded, because he felt its derisive tone toward others was too contentious a path to follow.

When “the movement” is discussed, it needs to be pointed out that invidious comparisons are made at the outset by the way we speak about its diverse aggregate. It’s fruitless to talk about a-theists, a-gnostics, secularists, pagans and related nomina because they are inherently pejorative. With the use of the alpha privative in a-theist and a-gnostic, for example, the assumption is already made these “infidels” are second-class knockoffs of their real-deal theo-believing counterparts.

You will see articles such as: “Is goodness without God good enough?” and “Why Americans Hate Atheists.” Arkansas, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas still retain articles in their constitutions that prohibit atheists from holding public office. Maryland’s requires a belief in God to serve as juror or witness. And it seems the long-standing shibboleth that no atheist will ever be elected President of the United States remains true to this day.

In his 175-page “Life After Faith: The Case for Secular Humanism,” published last year, Philip Kitcher provides a systematic and somewhat convincing argument for how a person can lead a moral life without God and formal religious beliefs and institutions.

I keep saying “formal” as in institutional because humanists do have beliefs based in religious values. And they are religious because “religion” comes from the Latin religare, which means to bind, to connect to the world around you.

And, even if we accept Cicero’s derivation that religion comes from relegere (to treat carefully) — the religiosi were those who took seriously all things pertaining to the gods — the aforementioned derivation holds true because we treat with care those to whom we’re bound. That is the nature of pietas.

But the issue of whether a person who lives a fact-based as opposed to faith-based life can live a moral life remains the wishbone of contention, so it is not surprising that Charles Darwin is turned to because through his work he reminded us that the basis of moral values is found in our social natures. He did say his “theory will lead to a new philosophy.”

I’m not here to provide an apologia for “secular humanism,” no, scratch the secular part, only to point out that our “social instincts” — a 19th-Century phrase that still retains legitimacy — allow us, as Darwin said, “to take pleasure in the society of [our] fellows, to feel a certain amount of sympathy with them, and to perform various services for them.”

And sympathy here does not mean the now-commonly-accepted feelings of pity and sorrow for someone suffering loss but more feeling bound to others in meaningful relationships that require care and, at the most basic level, reciprocity. Let’s call it an economic-based empathy.

And the tool that enables empathetic-bound-to-other-persons to proceed firmly on moral ground is the imagination. When I see your suffering, I imagine myself to be similarly situated, to be you, and I am moved to action.

I am also moved to envision new ways of being, of creating social institutions and societies in which suffering is eliminated. But, since pain and suffering are part and parcel of the human situation, that envisioning manifests itself through a society in which pain and suffering are responded to with loving care, in which structures are set up to meet human needs at all levels.

The great 20th-Century American poet Wallace Stevens in his poem, “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour,” comes up with the astounding “God and the imagination are one.”

That is what the humanists are saying, that they have in their power the tool to imagine all as one, and that that connectedness is the basis of all moral values (and subsequent remorse when harm is done), and that a Supreme Being of any sort seems if not inconsequential highly superfluous.

Enterprise file photo — Marcello Iaia

“Self-discipline” was defined by William Bennett as, “controlling our tempers, or our appetites, or our inclinations to sit all day in front of the television.” Modern Berne-Knox-Westerlo students last year got a taste of earlier school discipline when they visited a one-room schoolhouse in Knox.

In his memoirs, Ben Franklin wrote, “There was never a truly great man that was not at the same time truly virtuous.” I’m not sure who “The Prophet of Tolerance” would put in the category of “great men” today, but I am sure he would not call them virtuous because the words “virtue” and “virtuous” have all but disappeared from our vocabulary.

Even “habit,” as a disposition of the soul — and long associated with virtue — is non courant and might explain in part a growing concern about the loss of the “virtue” of self-discipline.

Years ago, William Bennett, who served as the nation’s first drug czar under George Bush (the 41st president), was bothered by this erosion in cultural values and took it upon himself to assemble a more than 800-page tome called “The Book of Virtues: A Treasury of Great Moral Stories.” This “‘how to’ book for moral literacy” is filled with poems and stories Bennett hoped kids would read and “achieve at least a minimum level of moral literacy” through the development of “good habits.”

He showcased 10 virtues among which were “compassion,” “courage,” “honesty,” “loyalty,” and “self-discipline” — the last of which he begins the book with — the “controlling our tempers, or our appetites, or our inclinations to sit all day in front of the television.”

I went back and looked at what Bennett said about discipline because there were several articles in the newspapers recently in which discipline took center stage.

On March 14, Paul Sperry of The Post wrote a piece called “How liberal discipline policies are making schools less safe.” Sperry said, “New York public-school students caught stealing, doing drugs or even attacking someone can avoid suspension under new ‘progressive’ discipline rules adopted this month.” Id est: The inmates are running the asylum.

Such a take on self-control is not new. In his column a while back, psychiatrist Greg Smith bemoaned the erosion of discipline at home and school alike.

In school, he said, teachers were “hamstrung” and at home, “Parents do not feel that they make the rules anymore. There can be no house rules. There can be no punishments, behavioral or corporal or otherwise, because Little Johnny has the Department of Social Services on speed dial on his $600 iPhone and will call them if his parents lift a finger to keep order in their own home.”

A cynical assessment from a psychiatrist and a pretty paranoid kid, unless of course he knew something we didn’t.

But Bennett comes to the rescue with a solution for how to handle such unrestrained beings using the words of Hilaire Belloc’s poem “Rebecca.” Belloc says there was “a wealthy banker's little daughter,” Rebecca, who was “aggravating” and "rude and wild" and made "furious sport" by “slamming doors” in the house startling the h-e-double-hockey-sticks out of uncle Jacob.

And because this little darling did not seem amenable to feedback, shall we say, someone in the family took it upon himself — or herself (it does not say who) — to set a heavy marble bust atop the door so that, when Rebecca blew through next and clapped the portal shut, the bust came down and killed her on the spot.

Rebecca’s good points were mentioned at the funeral but a warning was sent to those situated similarly to "The Dreadful End of One/Who goes and slams the Door for Fun." Through the words of Belloc, the drug czar’s riposte of neutralization makes boot camp seem like vacationing in Rome.

Then there was the article in The Times on March 11 about the Arkansas senator, Tom Cotton, who was responsible for “the” letter to the leaders of Iran urging them to not make a deal with the Obama Administration on nuclear arms.

Cotton’s fans and detractors both said he was highly “disciplined.” But retired Army General Paul D. Eaton, a senior advisor to the National Security Network, said, “The idea of engaging directly with foreign entities on foreign policy is frankly a gross breach of discipline.”

What! Is there a good discipline and a bad discipline? Can one stay in bounds in some arenas and then transgress boundaries in others? Such a division would seem antithetical to self-control.

To prevent the transgression of boundaries and the harm it creates — which might include tempers flaring and appetites spilling out onto the floor of the world — for ages monks “took the discipline,” that is, used a cattail whip of knotted cords (itself called a discipline) to lash themselves across the back during prayer. Pope John Paul II was said to have taken the discipline and even brought his whipping belt on vacation.

But we know externally imposed discipline and neurotic attempts at controlling the self work intermittently and have no legs. E.g.: We’re speeding along, we see a cop, we slow down, a half-mile down the road we ramp it back to 80 — without a wisp of guilt. So much for the threat of boot camp.

Years ago, I was taken with the great classics teacher and philosopher Norman Brown’s famous Phi Beta Kappa speech at Columbia University in 1960 — another was Emerson’s at Harvard in 1837 — where he spoke about how to achieve a lasting discipline, far afield of any marble bust snapping the neck of a child across a door jamb.

Brown said the answer is enthusiasm and he explained to the assembled that the word comes from the Greek “entheos,” which means “god in us,” so that “the eyes of the spirit...become one with the eyes of the body, and god [is] in us, not outside.”

Who needs external control if you’re on fire with purpose and dedicated to actions that support life and can see their joyful effects?

Enthusiasm excludes high performing, automaton, grade-mongering students in schools and rigid automatons in the workplace. Research shows kids in that boat tend to be superficial in their thinking, less creative, and let go of what they learned when the pay-off ends (when the cop is out of sight). It’s doubtful whether such souls will ever become one of Franklin’s virtuous few.

And, if you’ll recall, the aforementioned Mr. Bennett was a “preferred customer” big-stakes gambler at Atlantic City and Vegas and reportedly lost more than $8 million on Lady Luck’s $500-a-pull-slots and other games of fate.

When Bennett was brought to task for what seemed a contradiction in the words v. deeds department of self-discipline, his ideological ally, William Kristol, editor of The Weekly Standard, said that it was a matter between Mr. Bennett, his wife, and his accountant.

I thought it was an issue of controlling appetites. Would anyone on fire for life give even a passing glance to the capricious lure of Fortuna? Enthusiasm would never stand for it.

— From the U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers

Howard Stansbury, a civil engineer, was a captain. His only known image is from a carte d’visite; on the back is a handwritten note, attributing his 1863 death “to disease contracted in the Rocky Mountains.” He was born in New York City on Feb. 8, 1806.

In 1852, the United States Senate published the findings of Captain Howard Stansbury’s 1849-1850 expedition to the Great Salt Lake. The report was called “Exploration and Survey of the Valley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah: Including a Reconnaissance of a New Route Through the Rocky Mountains.”

Stansbury, an officer in the Corps of Topographical Engineers, had been assigned by the Senate to travel from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to the Great Salt Lake to scout out emigration trails, especially locations that might benefit the coming continental railroad.

The report is comprised of entries of what Stansbury and his team saw and did each day. Scientists were thrilled with his takes on new flora and fauna and the animals they came across, as well as the captain’s account of the Mormon community with which he lived one winter under the direction of Brigham Young.

Ethicists were thrilled with what Stansbury had to say on May 30, 1850 while walking along the shores of Gunnison’s Island situated in the middle of the lake, a key breeding ground for the American white pelican.

Stansbury was admiring the flood of pelicans along the shores of “the bold, clear, and beautifully translucent water” when he came across “a venerable looking old pelican, very large and fat,” which allowed Stansbury to approach him “without attempting to escape.”

More striking was the pelican’s “apparent tameness [and when] we examined him more closely,” Stansbury says, “[we] found that it was owing to his being entirely blind, for he proved to be very pugnacious, snapping freely, but vaguely, on each side, in search of his enemies, whom he could hear but could not see.”

And because the pelican “was totally helpless,” Stansbury knew he “subsisted on the charity of his neighbors, and his sleek and comfortable condition showed, that like beggars in more civilized communities, he had ‘fared sumptuously every day.’”

Pelicans are piscivorous, fish-eaters, and, since the salinity of the Great Salt Lake allows few fish to thrive, adult pelicans on Gunnison travel more than 30 miles one way to get food for their young — and their blind “comrade.”

An admiring Lewis Henry Morgan included Stansbury’s story in his classic “The American Beaver,” published in 1868, but perhaps more tantalizing is that Mr. Charles Darwin recorded that act of empathy in “The Descent of Man” three years later.

Though acts of mutual aid do not fit nicely with “survival of the fittest,” Darwin avers in “The Descent of Man,” “I have myself seen a dog, who never passed a cat who lay sick in a basket, and was a great friend of his, without giving her a few licks with his tongue, the surest sign of kind feeling in a dog.”

He offers examples of other dogs, baboons, elephants, cattle, and birds acting toward their comrades with a “moral instinct” that can only be construed as empathy.

The scientist and philosopher-anarchist Peter Kropotkin knew of the pelican story and referenced it in “Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution,” published in 1902. In the first two chapters, Kropotkin offers a host of examples of animals coming to the aid of each other when needed.

And, in an oft-cited lab experiment dealing with animal empathy — written up in the “American Journal of Psychiatry” in 1964 — Jules Masserman and his team at Northwestern University tested to see if monkeys would give one up for the Gipper, as it were, when called upon.

The experiment allowed rhesus monkeys to pull a chain to access food but, when they did, a monkey next to them was zapped with an electric shock. After a time, the monkeys refused to pull the chain — maybe Masserman should have pulled the plug at this point — one monkey not eating for 12 days, risking starvation to avoid paining another.

On Gunnison, what went on in the pelicans’ minds such that they “felt” compelled to bring fish for a useless comrade? Or what makes the famed meerkat risk death when serving as a lookout for his foraging clan? Can we attribute such acts to protoplasm alone?

Several years ago, Voorheesville veterinarian Holly Cheever told me a story of her earliest days of practice with dairy farmers in upstate New York.

She said she got a call one day from a farmer complaining that one of his brown Swiss cows — who just delivered a calf on pasture (her fifth for the farmer) — when brought onto the milking line, was found to have a completely dry udder. It could not have been the calf because her calf had been taken right after birth — standard practice.

The dry-udder situation continued for days when the bottom line says a new mother should produce one hundred pounds (12.5 gallons) of milk a day. The farmer was at his wit’s end.

Cheever reiterated last week that the mother was healthy, she was following the routine of the other cows — out to and back from pasture — but still no milk.

Finally, on the 11th day, the hapless farmer followed the cow and saw her head into a woods at the edge of the pasture where, mirabile visu, he saw a calf waiting for his mother whom she fed at her heart’s delight. She had given birth to twins!

If she had hid both calves, the farmer would have known right away; all things being equal, a pregnant cow would not go out to pasture and come back with nothing.

I think, as Chever does, that this cow had a maternal sense of justice. She had already given the farmer five babies, all taken right after birth. Now that she birthed two at once, she figured: One for him, one for me! She tipped the scales of justice her way.

Cheever said, “All I know is this: There is a lot more going on behind those beautiful eyes than we humans have ever given them credit for, and, as a mother who was able to nurse all four of my babies and did not have to suffer the agonies of losing my beloved offspring, I feel her pain.”

I know about the Animal Protection Federation and the recent efforts of Albany County District Attorney David Soares enabling authorities to better respond to, and prevent, animal abuse in the county.

But I remain stunned as to how folk can harm our compatriots who tell us in a million different ways where we came from and how we might better ourselves by offering aid to every blind pelican that comes our way.

I’m sure most people, when asked to provide a list of emotions they experience in a given month, would not include “schadenfreude” even though it rears its head often enough.

Coming from the German “schaden,” which means harm, and “freude,” meaning joy, the experience is one of feeling pleasure at the misfortune of another.

It’s a strange emotion to be sure because we usually associate joy with a pleasant outcome whereas schadenfreude is pleasure derived from another’s ill.

And the experience is universal. William James in “Principles of Psychology” says, “There is something in the misfortunes of our very friends that does not altogether displease us; [even] an apostle of peace will feel a certain vicious thrill run through him, and enjoy a vicarious brutality, as he turns to the column in his newspaper at the top of which 'Shocking Atrocity' stands printed in large capitals.”

Indeed researchers who seek to quantify its presence in our lives say schadenfreude is on the rise. In “The Joy of Pain: Schadenfreuse and the Dark Side of Human Nature,” Richard Smith says he looked at the number of times “schadenfreude” appeared in the English language from 1800 to 2008. In modern times, he says, from the 1980s on, schadenfreude as concept and “practice” has achieved a greater share of our emotional landscape.

I’m inclined to think it’s because we’ve become a more punitive and cynical society, maybe even more sadistic, and schadenfreude is one of the manifestations of that callousness — though schadenfreude is not in the same ballpark as sadism (or even gloating), which are more actively aggressive in nature.

Because schadenfruede is etymologically German, for years critics characterized it as a peculiarly German phenomenon, especially during World War II! But, when we examine the spectrum of world cultures, we see that every culture has its own word or combination of words to denote this emotion or some approximation of it.

The French have their “joie maligne,” Hebrew has “simcha-la-ed,” and ancient Greek has “epichairekakia,” which ancient as well as modern scholars say is a distant relative of greed, avarice, and envy.

In Japanese, there’s “meshiuma,” which means, “Food tastes good that comes from the misfortune of others.” The writer Gore Vidal once remarked, “Every time a friend succeeds, I die a little.” The converse would be, “Every time a friend fails, I am more alive” and the double converse, “I derive pleasure from the misfortune of others.”

For those unfamiliar with the word (I will not say the experience), an example might be helpful at this point.

We are driving along our favorite county road, staying well beneath the 30-mile-per-hour speed limit because the road is highly patrolled. All of a sudden, a large SUV appears in the rearview mirror with a young kid at the wheel and he’s up our bumper.

Staying our course, we see the “kid” begin to wave his arms in what seems to be gestures of anger; he then pulls out over the double yellow line and guns it past us. As his passenger window nears ours, he looks down at us with derision and double-guns it up the hill and out of sight.

A few moments later, as we near the hill, we see his car pulled over and a cop writing him a ticket. If we feel a certain satisfaction at this point and think something like, “He got what he deserved,” or, “Justice triumphed,” or, “There is a God,” we are in the schadenfreude business.

When Martha Stewart was indicted in 2001, the United States experienced a kind of national schadenfreude. People felt that the person who had dictated personal and social tastes for years finally got her comeuppance.

There is some debate over whether the shadenfroh’s delight comes from the bodily pleasure produced or seeing society’s fabric saved. In other words, was justice done to the nervous system or to the collective? And there is strong evidence that shows when the experienced misfortune is great, schadenfreude all but disappears and a hybrid form of empathy kicks in.

Understandably schadenfreude has been linked to envy because when we envy another’s possessions or achievements, we engage in an internal (and often subtle) trash-talk dialogue, subconsciously trying to improve our own lot. People pay big money to therapists for years to understand and get out from beneath such a complex.

The irony is that people will talk about schadenfreude experiences openly whereas they are far more reluctant to speak about what they envy because envy is an open admission of inferiority.

Of course the moral implications of schadenfreude have not gone unnoticed. In Spanish there is a saying: Gozarse en el mal ajeno, no es de hombre buen (“A man who rejoices in the misfortunes of others is not a good man”). Or should we say is a person who has not reached emotional maturity?

We do know that when schadenfreude is primed with emotional steroids, the frequency and intensity of its presence leads to the destruction of relationships. When I first came upon schadenfreude years ago, I immediately thought of the great psychoanalyst Karen Horney’s concept of “vindictive triumph,” which she saw alive in her patients saddled with neurosis. Vindictive triumph might be viewed as schadenfreude when it becomes a structural part of our identity and one justified by a more highly toxic logic.

In “Neurosis and Human Growth,” Horney says the drive to vindictively overcome others grows out of “impulses to frustrate, outwit, or defeat [them] . . . because the motivating force stems from impulses to take revenge for humiliations suffered in childhood.”

Often enough, this chronic illness might be accompanied by headaches, stomachaches, fatigue, and insomnia because the drive to see others get their “due” is relentlessly churned up in the subconscious.

If vindictive triumph is indeed a compensatory mechanism, and schadenfreude and vindictive triumph are in fact manifesting themselves more frequently in our culture, as research suggests, what are we compensating for? Why has the need to triumph vindictively moved center stage? Why the need for such an array of trophies?

Heavy stuff indeed, but, as the United States continues to undergo its current identity crisis, understanding what drives people to increasingly take joy in the misfortune of others will enable us to forge a less aggressive future self. Maybe that’s what the great American poet Allen Ginsberg was alluding to when he said, “Candor disarms paranoia.”

La Grande Chartreuse is the head monastery of the Carthusian order and is situated in the Chartreuse Mountains north of Grenoble, France. The order, founded in 1084 by St. Bruno, follows rules called the Statutes. Visitors are not permitted at the monastery and motor vehicles are prohibited on nearby roads. Philip Gröning’s movie about the monastery, Into Great Silence, is available for loan at both the Voorheesville and Guilderland public libraries.

Nearly 50 years ago, I made a rule never to recommend movies, restaurants, and vacation spots to anyone save a few intimates whose number today I gladly count on half a hand.

And though I firmly believe rules are made to be kept, I’d like to call attention to Philip Gröning’s 2005 documentary on the Carthusian monks at La Grande Chartreuse, the Carthusian motherhouse in the valley of the Alps of Dauphine north of Grenoble, France.

The highly critically acclaimed film is called Into Great Silence and its tourdeforcity is a human magnet.

At a period when Gröning was obsessed with trying to understand “time,” he wrote to the superior of the 4,268-foot high Carthusian charterer house seeking permission to record the life of the monks. The superior wrote back saying they wanted to think about it. Sixteen years later, Gröning received a reply saying they were ready, if he still had interest.

He did and arrived at the monastery in mid-March 2002 as a team of one: the film’s director, producer, cameraman, soundman, grip, and whoever else was needed to get the job done. To fully grasp the depth of silence the monks lived in, Gröning decided to live with them and follow their highly structured horarium.

And though the monks chipped in to help Gröning move his equipment up mountainous slopes surrounding the monastery when needed, the director was solely responsible for lugging his tools.

One day, while shooting along a steep ridge, he fell 20 feet and found himself spread out on a slab of stone thinking his day had come. It hadn’t, and after a bit he was back shooting the 120 hours of film that served as the vein from which he mined the 162 minutes that comprise Into Great Silence.

The editing was harrowing for Gröning; it took him more than two-and-a-half years to find a proper narrative. He could not find the glue to hold things together.

Those familiar with Roman Catholic religious orders know the Carthusians are the strictest of all. The monks live in near-total silence, spending most of the day in their cells (warmed by a tin-can-shaped wood-fired stove) and in a walled-in garden.

In these spaces, the monks meditate, pray the liturgy of hours, read, write, and eat alone. Each monk washes his own clothes, does his own dishes, splits his own wood (it gets cold there), and works in the garden for exercise and cultivating plants.

The monks are also assigned communal chores to support the upkeep of the house. For some, this means making the green-colored Chartreuse liquor for which the monks have been famous for centuries.

Some have said the highly structured schedule leaves no “free time” for the monks, but the monks say their whole life is free.

They do leave their cells to chant in the chapel and celebrate Mass. On Sundays, they eat together in silence as one of the monks reads aloud and once a week they take a walk in the woods for hours where they converse about “edifying” things. Gröning caught the monks sliding down the snowy slope of a hill, yelping like kids on holiday, using their shoes as sleds.

Twice a year, the monks may receive a daylong visit from family members, and the silent grounds of the monastery grow abuzz with the chatter of kids and adults alike. Though not of this world, the Carthusians recognize the importance of the human feelings and the connections the monks had (have) with the families they grew up in.

They sleep no longer than three hours or so at a time. To bed at eight, they’re up past eleven praying and singing psalms, then back to sleep for three hours, and up again to celebrate more lectio divina. Those who persevere after the novitiate spend an average of 65 years in the monastery doing the same thing every day of every year, with no place to go and no apparent goals.

Gröning beautifully captured their spirit on film and I recommend it because it does deal with “time” in that it shows human beings who treat each moment of life as if it were the totality of that life and who find happiness in such gestures of gratitude. If you watch the film, it will blast smugness out of every bone.

When I speak to Roman Catholics about the film, more than a few claim the movie is a Roman Catholic venture because the Carthusians are a Roman Catholic order. And I tell them they are reading it wrong because the movie is about human beings who fully appreciate what life presents to them each moment of the day, and that that human possibility is not sectarian but belongs to everyone.

I saw the movie at the Spectrum 8 in the city of Albany when it first came out and it knocked my socks off. I was back three days later for a second sock-knocking. I’ve watched it on DVD after that but judiciously because it is such a workout.

The writer Adair Lara said that, when she was growing up, her mother “used to wash our clothes in a wringer washer and then hang them on the clothesline outside. As she pinned up each garment, she said, she thought about the child it belonged to. She never wanted a dryer, even after we could afford one, because it would steal this from her, this quiet contemplation.”

That woman understood the great silence of La Grande Chartreuse, aware of the precious gift that every moment is, realizing that that gift could disappear in the blink of an eye.

If you decide to watch the film, pour yourself a beer or cup of tea, or whatever you like to have at the movies, sit back, and give yourself over to the life ahead without interruption.

You will be transported into another world of time and space and perhaps like me return transformed, an appreciator of the soil in which great silence is born.

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, who lived from 1793 to 1864, has long been heralded as Guilderland’s most prominent son, in these pages and elsewhere.

In his local history classic Old Hellebergh, published in 1936, the late Guilderland town historian, Arthur Gregg, said, “There has never been in the long category of soldiers, patriots, statesmen, manufacturers, educators, and jurists, born and reared in sight of the ‘Clear Mountain,’ [the Helderbergs] one with more fame than the pioneer . . . Henry Rowe Schoolcraft.”

A Renaissant-like omnivore of human experience, Schoolcraft was a glass manufacturer early in life, then a mineralogist, then a geologist, explorer, ethnologist, poet, editor, and for 19 years, from 1822 to 1841, served as United States Indian Agent headquartered at the frontier posts of Sault Ste. Marie and Mackinac Island, assigned the tribes of northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.

To many folklorists, Schoolcraft is considered the first “scholar” to amass and publish a body of Indian folklore and deserves to be called the father of American folklore. When he arrived in Michigan, he lived with the family of John Johnston, an Irish fur trader who married the daughter of a prominent Ojibwa war chief and civil leader from northern Wisconsin.

Schoolcraft married Johnston’s daughter, Jane, who provided him with a host of Chippewa legends. His mother-in-law gained access for him to stories from “the greatest storyteller of the tribe” and to ceremonies open only to tribe members.

Schoolcraft’s ethnological findings were published in many volumes, the magnum opus of which is his six-volume folio-size Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, published between 1851 and 1857, and costing $150,000.

As editor and writer, Schoolcraft, in 1826 and 1827, produced a much-sought-after weekly journal called the Literary Voyager. The 15 issues constitute the first magazine produced in Michigan and one of the first to appear in the frontier west.

Schoolcraft’s accomplishments have not gone unnoticed. In the Midwest, particularly Michigan, the Schoolcraft name is ubiquitous. A Michigan County is named after him, a town, a village, river, lake, island, highway, ship, park, and even the culinary arts Schoolcraft College in Garden City, Michigan has a food court called Henry’s.

As a person with an abiding interest in local history, I paid due attention to Schoolcraft over the years, particularly his relationship with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow whose epic poem, “The Song of Hiawatha,” was based on information Schoolcraft published.

But what enthralled me most about Schoolcraft was a touching one-page story I came upon two years ago when I was looking at Oneóta or Characteristics of the Red Race of America, published in 1847. It is called “Chant to the Fire-Fly.”

Schoolcraft relates that on hot summer evenings before bedtime Chippewa children would gather in front of their parents’ lodges and amuse themselves by singing chants and dancing about.

One spring evening, he says, while walking along St. Mary’s River, the evening air “sparkling with the phosphorescent light of the fire-fly,” he heard the Indian children singing a song to the firefly. He was so taken with the chant he jotted it down in the original “Odjibwa Algonquin [sic].”

Below the text, Schoolcraft offered two translations of the chant — one “literal,” the other “literary” — of a song he says that was accompanied by “the wild improvisations of [the] children in a merry mood.”

I will not give the Ojibwa — you can find it on page 61 of Schoolcraft’s Oneóta — but I will provide Schoolcraft’s literal translation. After I read the poem several times, I could not escape its charms. I envied Schoolcraft that evening when he first heard the children sing. This is his translation:

Flitting-white-fire-insect!

Waving white-fire-bug!

Give me light before I go to bed!

Give me light before I go to sleep!

Come little dancing white-fire-bug!

Come little flitting-white-fire-beast!

Light me with your bright white-flame-instrument—

Your little candle.

I was so taken with this text that I wrote two poems about the firefly and started looking deeper into the story but the more I did the more I smelled something rotting in Denmark.

That is, I found a chorus of folklorists, linguistic anthropologists, ethnopoeticists [mine], and those of that ilk, taking Schoolcraft to task for being a “textmaker” rather than a scientist dedicated to taking down the Indian world as it presented itself to him.

Schoolcraft wanted to produce something “literary” (marketable), and to achieve that, he engaged in mediating between what the Indians said and what a projected readership might accept from the “savage.”

Schoolcraft says he began to weed out “vulgarisms,” he “restored” the simplicity of style, he broke legends “in two,” “cut [stories] short,” and lop[ped] off excrescences.”

In the introduction to The Myth of Hiawatha and Other Oral Legends, published in 1856, he said the legends had been “carefully translated, written, and rewritten, to obtain their true spirit and meaning, expunging passages, where it was necessary to avoid tediousness of narration, triviality of circumstance, tautologies, gross incongruities, and vulgarities.” In other words, what did not fit his aesthetic and religious views of reality, went.

While giving credit to Schoolcraft for his pioneering work, the early 20th-Century folklorist Stith Thompson noted, “Ultimately, the scientific value of his work is marred by the manner in which he reshaped the stories to suit his own literary taste. Several of his tales are distorted almost beyond recognition.”

This is not an imposition of postcolonial standards on Schoolcraft’s doings. As Richard Bremer points out in his full-length biography of Schoolcraft, Indian Agent and Wilderness Scholar, even Francis Parkman told Schoolcraft to stick to the facts.

Though he often exhibited paternalist sympathies with the Indians, Schoolcraft signed treaties as the Indian Commissioner for the United States that displaced the Michigan Indian. The Treaty of Washington in 1836, concluded and signed by Henry Schoolcraft and several representatives of the Native American nations, saw approximately 13,837,207 acres (roughly 37 percent of the current State of Michigan) ceded to the People of the United States.

I went over to Willow Street the other day to visit Henry’s house, waiting in the cold outside, thinking he might come out. I have many questions for Henry Rowe Schoolcraft.

Peter Henner, a lawyer from Clarksville, wrote an award-winning chess column for The Altamont Enterprise, "Chess: The Last Frontier of the Mind," for four years, retiring from the column in the fall of 2014 to resume his law practice on his own terms. His columns are archived here.

In the winter of 2015, Dennis Sullivan, a scholar and historian from Voorheesville, began his column "Field Notes."

Crossword puzzle lovers may have wondered about the frequent clue “Russian chess champion” (three letters). The answer is “Tal,” as in Mikhail Tal, who died on June 28, 1992. The “Magician of Riga,” as he was known, Tal became the eighth World Champion in 1960, at the age of 23.

The Soviet-Latvian Grandmaster, who had been terrorizing the chess world for the previous five years, particularly the relatively staid Soviet players, with his unorthodox style of play, was, at the time, the youngest player to win the world championship.

Tal was known as a brilliant attacker, a creative genius, who played intuitively and unpredictably. Today, with modern computers, we know that many of his speculative sacrifices were unsound and should have lost.

Tal himself said “There are two types of sacrifices: correct ones, and mine.”

However, it was not easy, even for the world’s best players, to refute these sacrifices over the board, and contemporary analysts usually were unable to show why or how Tal could have been defeated.

His style was a challenge to the Soviet school, exemplified by Mikhail Botvinnik, which preferred systematic logical chess, buttressed by hard work and study. Botvinnik, who, with one interruption, had been Champion since 1948, prepared carefully and methodically for the 1960 match.

Tal, in contrast, simply played a tournament in his hometown. Tal decisively won the match by a score of 12 ½ - 8 ½.

However, the Fédération internationale des échecs rules at the time permitted a rematch for a defeated Champion, which Botvinnik won, 13-8.

In the second match, Botvinnik, once again carefully preparing for the match, deliberately played for closed positions, leading to positional struggles and endgames, and avoiding the sharp tactical play that Tal loved.

During the rematch, Tal continued to play his favorite Nimzo-Indian Defense and the aggressive advance variation of the Caro-Kann, even as it became clear that these openings were not working for him. It was not until five years after the match that Tal, playing White against Botvinnik, abandoned the advance variation in favor of the more common Panov variation and won easily.

Tal had a great career, winning the USSR championship six times between 1957 and 1978 (when that tournament was probably the strongest tournament in the world), established a record in 1973 - 74 by playing 95 tournament games without a loss (46 wins and 49 draws), and tied with Karpov for first in the 1979 Montréal “Tournament of Stars.”

Although he continued to compete in world championship cycles, he never again played a match for the world championship. However, at the age of 51, he won the World Blitz Championship ahead of then world Champion Kasparov.

Tal died young: He suffered from serious health problems all his life, complicated by chain-smoking, excessive drinking, and partying. His wife, Salli Landau (they were married from 1959-1970), who wrote a biography of Tal, noted that, while some people thought he might have lived longer by taking better care of himself, if he had done so, he would not have been Tal.

She also commented that Tal “was so ill equipped for living… When he traveled to a tournament, he could even fact is on suitcase… He didn’t even know how to turn on the gas for cooking…Of course if he had made some effort, he could have learned all of this. But it was all boring to him. He just didn’t need to.”

In the spring of 1992, shortly before he died, Tal escaped from his hospital room to play in a blitz tournament. The following game, played against Kasparov, is generally regarded as his last game.

Tal –Kasparov 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. Bb5+ Nd7 4. d4 Nf6 5. O-O a6 6. Bxd7 Nxd7 7. Nc3 e6 8. Bg5 Qc7 9. Re1 cd 10. Nxd4 Ne5 11. f4 h6 12. Bh4 g5 13. fe gh 14. ed Bxd6 15. Nd5 (a Typical Tal move! Houdini says the position now goes to -2.0 for Tal) ed 16. ed+ Kf8 17. Qf3 and Black forfeited on time.

The computer says Tal is losing, but it is not so easy to meet the threats on the board. And so Tal leaves the game as he found it, playing aggressively, speculatively, for the fun and joy of the game.

No column for the summer

I have been writing this column for more than four years, and am going to take a break for the summer, until late August.

In the last year, I have put a lot of energy into chess — playing, studying, writing about it — and I want to take some time to do some self-evaluation, decide whether I want to keep doing as many chess things as I have been doing.

This week’s problem

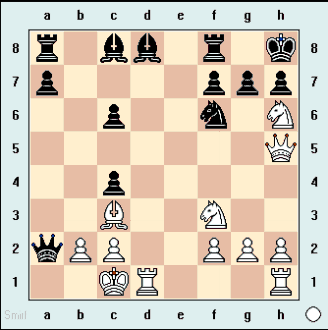

Here Tal finds a neat mating attack against former world champion Vasily Smyslov, who had also defeated Botvinnik for the world championship (in 1957) only to lose a rematch the following year.

After the crucial first move, White mates in no more than four moves.