When geology led to tragedy: The Death of Floyd Collins

The death of farmer and caver Floyd Collins and the subsequent grotesque events — including some legendary ghost stories — constitute a strange chapter in the annals of American folklore. The setting for the tales is the vast karst area of central Kentucky known as the Chester Upland under which the corridors of Mammoth Cave, the world’s longest, wander for over 500 miles beneath the forested plateaus.

Derided all too frequently as hillbillies and rednecks, its proud, hard-working people and their ancestors have struggled mightily to sustain a life farming the thin soils or doing service work. While those fortunate enough to live between Interstate 65 and Mammoth Cave National Park may enjoy some advantages derived from tourism, on a recent trip to the Park I found it sobering to see how many tourist shops, restaurants, and entertainment venues stand empty, even at a time when much of the rest of the country is enjoying a rising economy.

And the situation has long been the same. Early in the 20th Century, as the automobile created a boom in tourism, the wonders of Mammoth Cave became a magnet for the more adventurous visitors. But the Chester Upland is, as the saying goes, honeycombed with caves, many on private lands — some connected to Mammoth, some isolated from the great cave in discrete, thickly-wooded parts of the plateau known as Mammoth Cave Ridge, Flint Ridge, and Joppa Ridge, among others.

The cave entrances are surrounded by deep, densely-forested valleys populated by rattlesnakes, copperheads, and herds of deer, mysterious places where some of the hundreds of diminutive streams that flow through them are swallowed by gaping fissures in the bedrock or emerge in cascades from mossy, bubbling springs.

Many have entrances that challenge even modern explorers with high-tech gear: vertical pits requiring rope work or tiny entrances involving contortions through tortuous passages. But some have easy walk-in entrances that in ages past allowed visitors with hand-held lanterns to seek out their wonders.

The Cave Wars

And thus were precipitated the Cave Wars, in which a farmer known as Floyd Collins became the only known fatality. A relatively little-known part of American history, the Cave Wars came about as various private owners of central Kentucky caves competed to draw in tourists.

When the new-fangled automobiles came chugging down the stretch of gravel road between Cave City and the entrance to then-privately-owned Mammoth Cave, their drivers were confronted with a bewildering array of billboards promoting caves with confusing names like Colossal Cave, Mammoth Onyx Cave, Onyx Cave, Great Onyx Cave, New Entrance Mammoth Cave, and a host of others.

Promoters — some of them dressed to resemble state troopers or other enforcers of the law — would wave drivers over and present them with misleading information about the location of the actual entrance to Mammoth Cave. Sometimes they told outright lies to the effect that Mammoth was no longer accessible, its entrance having collapsed, or would tell travelers that their own caves offered collections of beautiful crystalline formations that far surpassed anything to be seen in Mammoth — and there was some truth to this claim.

But the fact was: For the adventurous tourist, caves were a big attraction and their dollars were a big attraction for the cave owners, and it seemed that no tactic was too extreme — some involving threats of violence or the vandalizing of a rival’s cave.

Blackness that beckoned

On remote Flint Ridge, far from the world of tourism, a family by the name of Collins had long raised tobacco, corn, and other crops. Flint Ridge is a beautiful place, lushly forested and dotted with old pioneering-family cemeteries and churches and formerly-farmed fields that have now returned to woodland since the creation of Mammoth Cave National Park in 1941.

The small farmhouse in which the family had lived for generations has been restored by the National Park Service and stands as a reminder of the spare lives of its inhabitants.

The Collins family members were surely aware of the money that could be made from exhibiting a privately-owned cave to the visitors who traveled to Kentucky from all over the country, and at least one of them, Floyd Collins, set off in his free time in search of a cave on their property.

Astoundingly, just a few hundred feet from the farmhouse, Floyd found a rocky fissure that was blowing cold air. Though the fissure and the passage beyond it were at first too small to admit anyone except on hands and knees, the cold wind blowing told him that something big lay in the blackness that beckoned.

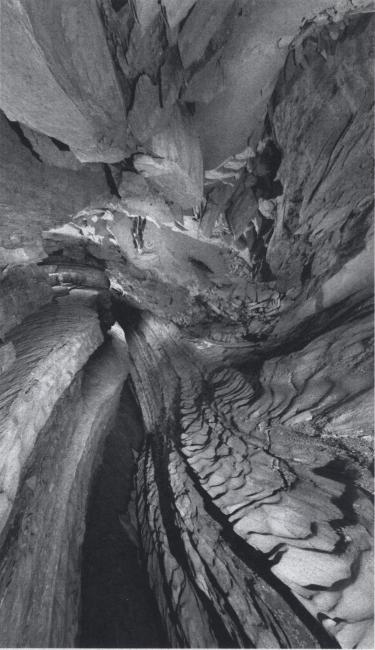

Floyd and his brothers began clearing away rocks and soil to allow them to penetrate farther into the cave and — again, astoundingly — just a few hundred feet in, the floor dropped away and the cave opened into an immense passage subsequently named “the Grand Canyon.”

But this was just the beginning of what would, after many years of exploration, yield over 80 miles of passages. Floyd named the discovery “Great Crystal Cave” because of the spectacular gypsum formations found everywhere within it.

Often far more impressive than the usual stalactites and stalagmites characteristic of limestone caves, gypsum crystals can extrude from the bedrock like toothpaste from a tube and form intricate formations that may resemble flowers, vines, and tendrils.

During his free time, Floyd went off on his own to explore, using only a handheld lantern. Crawling, squeezing, and climbing, he spent days at a time in the cave, leaving caches of canned food to sustain him, which he would smash open with chunks of limestone. Eerily, some of these food caches — rusted and disintegrating — are still visible in the cave today.

He found miles of spectacular passages in places no one had been before — and, should he have gotten injured or lost, no one would have had any idea about where to find him. The route to one vast, impressive section subsequently known as “Floyd’s Lost Passage” died with him; it was not rediscovered until long after his death by intrepid explorers who marveled that he had been so bold as to go so far from the cave’s entrance — a distance of nearly two miles through a confounding maze of passageways.

Long after Floyd’s time, in 1972, a stream passageway was explored that flowed under the deep Houchins Valley and connected the cave to Mammoth.

Seeking a back door

Floyd and his brothers cleared walkways and made other improvements to draw tourists. But, despite its huge, impressive passageways and its stunning formations, Floyd’s cave had one major drawback: It lay on a remote section of Flint Ridge, on a dirt road that led through dense forest and past the old Mammoth Cave Baptist Church, miles from roads frequented by tourists — and few of them found their ways to Crystal Cave.

But Floyd knew that caves often have more than one entrance, and he concluded that what Crystal Cave needed was an entranceway close to a major highway — a “back door” so to speak. So, on his own as usual, Floyd began ridge-walking the thick woods where the Flint Ridge Road comes close to an intersection of highways called Turley’s Corners, which even today is a tourist area, with its tacky souvenir shops and canoe outfitters.

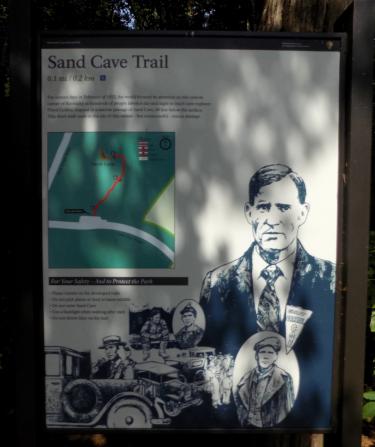

What lured him was a small entrance known as Sand Cave. It was only a couple of miles from Crystal Cave’s entrance and close to a much-traveled highway and, if it should turn out to be the back door to Crystal Cave, the opportunity for tourists to visit would be vastly increased.

The cap rock of much of Flint Ridge and the ridge to the west under which Mammoth Cave lies is a layer of sandstone known as the Big Clifty formation. It is a very thick, dense layer with a hardness approaching that of quartzite, which is metamorphosed sandstone.

It is essentially impermeable to surface water and is in many ways responsible for the fact that Mammoth Cave is the world’s longest; over millennia, it has prevented the dissolving and erosion of much of the surface rock, preserving the vast stretches of cave passages that lie beneath.

A dark, gloomy recess in a low cliff above a streambed surrounded by shadowy deciduous forest and poisonous vines, Sand Cave is basically a shelter like those found at the base of the cliffs on the Indian Ladder Trail in Thacher Park.

But in some places, such as at the head of one of the valleys that cut through the plateaus of the Chester Upland, the thick limestone layer known as the Girkin Formation is exposed; the Girkin lies directly beneath the sandstone and dissolves in acidified groundwater, forming caves.

At Sand Cave, Floyd Collins found a small passage extending back under the Big Clifty and into the limestone and the passage was blowing air — a sure sign that there is real cave within. So on a chill, damp day, Jan. 30,1925, Floyd hung his denim jacket on a handy tree branch, lighted his hand-held kerosene lantern, and crawled into Sand Cave.

He had told no one where he was going.

Fateful journey

Cave explorers are used to crawling through small, tight passages that can form in limestone caverns, and the mere description of them is often enough to give non-cavers claustrophobia.

Knox Cave in the Helderbergs has a famous (or infamous!) passage known as The Gun Barrel, which is 47 feet long and averages 14 inches in diameter, and has been known to give even seasoned cavers some very uncomfortable moments. But many such passages in limestone caves are stable — dissolved out of solid rock and not susceptible to sudden collapse.

The passage that Floyd crawled into that fateful day was essentially a squeeze hole through sediment: piles of sandstone and limestone blocks and boulders mixed with pebbles and sand and other small debris washed in from the outside.

Precisely what Floyd found is not known — but on his way back out, while crawling through a particularly nasty, wet, unstable section of passage, a 26-pound rock dislodged from the ceiling and pinned his leg. So tight was the passage that he could not move his leg to remove it and he was unable to turn around to do it by hand.

The more he struggled, the more debris came down until shortly he was encased in sediment up to his chest. A tiny, muddy stream from a channel in the ceiling was dribbling across his face — slow and steady torture.

And no one could hear him scream for help.

The search begins

When word began to circulate that Floyd had not returned home from one of his ridge-walking excursions, friends and family went out looking for him.

As it happened, a young man named Jewell Estes, son of a family friend, was out searching with his father and another man and spotted Floyd’s denim jacket hanging from the tree. Jewell crawled in to the point at which he could talk to Floyd and where he learned the awful truth.

What happened next is legend and is recorded in minute detail in the book “Trapped!” by Robert K. Murray and Roger W. Brucker. News of Floyd’s plight spread first across the plateaus, then across Kentucky, then across the country, and finally across the world.

Rescue attempts from the outset were terribly disorganized as one attempt after another to free him ended in failure. The area around Sand Cave became the site of what has been called grimly a “carnival” as crowds arrived to watch; then hawkers arrived, selling food and grotesque souvenirs such as balloons with “Sand Cave” printed on them.

Arguments and sometimes violent fights broke out over the best strategy to free Floyd. One shining light in the whole sordid affair was a young reporter from the Louisville Courier-Journal named William “Skeets” Miller.

A short, wiry, but powerful man, Miller made repeated trips down to comfort Floyd and bring him food; a generator was set up on the surface to provide electricity for a lightbulb that was brought down to Floyd to provide some warmth to his chest and some light to hold back the terrifying darkness.

Miller eventually won a Pultizer Prize for his reporting.

Crushing end

But it was all to no avail. After several days, a rockfall cut off access to Floyd and he was left imprisoned and alone in the wet sediments, which steadily drained away his body heat and he could no longer be fed.

A team made up of members of the Kentucky National Guard and enormous numbers of volunteers from many walks of life began an ambitious project to excavate a shaft down through the debris at the mouth of Sand Cave in hopes of then digging sideways to intersect the passage in which Floyd lay.

But 13 days after his entrapment, the rescuers arrived to find Floyd dead of hypothermia and starvation. It was a crushing end to a highly emotional drama. Sand Cave is today one of the historic sights of Mammoth Cave National Park, and a kiosk and a boardwalk guide visitors to its gloomy, shadow-enshrouded entrance.

The events that followed Floyd’s death are less material for tragedy than for grotesque comedy. Floyd was first buried in the family cemetery near the farmhouse on Flint Ridge. For a while, the notoriety of the events drew crowds to what came to be known as “Floyd Collins’ Crystal Cave.”

Members of Floyd’s family went on vaudeville lecture tours with slides and films of the events to captivate a certain kind of audience. But, after a time, the Collins family sold the farm and the cave and the new owner decided to capitalize on the tragic events by digging up Floyd’s coffin and placing it in Crystal Cave in the huge Grand Canyon passage.

Ostensibly this was an act of respect for the “Greatest Cave Explorer Ever Known” as carved on a massive granite monument that was installed at the head of the coffin. But visitors to the cave could also pay an extra fee to open the coffin to get a look at Floyd’s body that was preserved under glass. An undertaker dropped in on a monthly basis to keep the body presentable.

Evidently these morbid stunts were effective at drawing visitors to Crystal Cave and away from some of the other commercial caves in the area. In what must surely have been the most ghoulish event of the Cave Wars, one night someone broke into the cave and stole Floyd’s body.

It was found days later on a bank of the Green River minus one leg. The body was returned to its coffin and remained in the cave for many years.

Eventually, the National Park purchased the Collins farm and Crystal Cave and closed it to paying visitors, placing a padlocked steel gate at its entrance.

Finally, in 1987, at the request of descendants of the Collins family, the coffin and headstone were removed and taken to the Mammoth Cave Baptist Church cemetery on Flint Ridge where they remain. Cave enthusiasts from all over the world stop to pay a visit to this peaceful, remote site and leave behind flowers, coins, and other memorabilia.

Ghost stories abound

No one seems to know precisely when the ghost stories began but, starting in the 1950s, the Cave Research Foundation — an organization of sport cavers and scientists — undertook extensive, meticulous explorations in Crystal Cave that eventually led to its connection to Mammoth.

Everyone entering the cave had to pass by Floyd’s coffin, and a tradition began — for luck or superstition? — to call out “Come along with us, Floyd!” when researchers ambled past it on their way into the miles of labyrinths that lay beyond.

Seasoned researchers would occasionally report they heard footsteps behind them when there was no one there, or deep breathing from no known source — or a remote voice calling “Wait for me!” when it was known that there was no one else in the cave.

A hydrogeologist working in the cave was startled to hear a telephone ring — one that had been placed there for emergencies in the days when the cave was commercialized. When he picked it up, he reported sounds like chatter at a cocktail party before there was a loud gasp and the line went dead.

Shortly thereafter, he discovered that the line to the telephone had been cut many years before and lay rusting in the dust of the cave floor.

One of the most disturbing stories came from a husband-and-wife team who one night were doing some geologic studies in remote Floyd’s Lost Passage. No one else was in the cave that night and they had locked the entrance gate behind them.

Going to the passage involves a challenging series of crawls and climbs and the careful traverse of two very deep and dangerous pits. It also involves passing a site close to the beginning of the Lost Passage in which some of Floyd’s rusted cans of food are visible.

The two separated, working at two different locations several hundred feet apart. Suddenly, the incredible silence of the cave was broken by a pounding noise.

Each thought the other was the source of the sounds — but they were so rhythmic and so persistent that the two soon sought each other out — only to learn that neither was making the sounds. Undoubtedly, memories flashed through their minds of the fact that, when Floyd was exploring the cave for days at a time, he used a jagged fragment of limestone to smash open his cans.

These people are world-renowned scientists and are not given to superstition or hysteria. Nonetheless, they decided that, discretion being the better part of valor, they would exit the cave at once.

They have been back to the cave many times, but have never again heard the sounds, although other explorers have also reported pounding noises in remote sections of Crystal Cave. Often witnesses will keep such events to themselves.

But like perfectly reasonable, rational, knowledgeable people who have seen something that might be termed a UFO, an unidentified flying object, they will occasionally confide in a close friend or associate: “Wait’ll you hear what happened in Crystal Cave today … .”

Of course, caves are inherently black, mysterious places where the silence is sometimes so overwhelming that one can hear one’s own heartbeat. But the sad events at Sand Cave and the subsequent ghoulish ones that followed Floyd’s death can be stimulants to the imagination — or something more?

And it becomes easy, especially at this time of year, to imagine that on dark, windy Kentucky nights a restless presence may indeed wander the brooding forests of Flint Ridge or the mysterious, dusty labyrinths beneath it.